As William Feuer, a marvelous biostatistician and colleague, once said “If you design a clinical trial properly, there is no such thing as a failed study.” And, this is the truth: while a treatment may fail to achieve its pre-specified efficacy endpoint and prove beneficial to patients – the study has not failed, just the treatment. At the very least, a successfully executed study will give you a definitive answer, either yes or no. Moreover, the study outcomes should help you refine the design of future trials by providing additional natural history data. After all, showing that a treatment doesn’t work saves money, allows better allocation of resources, and prevents patients from being exposed unnecessarily to treatments. Similarly, there is nothing more frustrating than having a potentially valuable drug that could be a breakthrough therapy, but it fails to prove itself in a clinical trial, because the study was not designed correctly and appropriate endpoints were not chosen properly. Companies throw hundreds of millions of dollars at the clinical development of drugs, and they may be effective. But if the trials are designed poorly or conducted improperly, then what’s ahead is heartbreaking: all that effort, and you’re still left with questions as the results don’t answer the question you asked.

There is so much work that goes into writing an experiment and running a clinical trial that you absolutely have got to get an answer at the end of it. And this means designing a “bulletproof” clinical trial: setting up the study and necessary controls so you know the results will be meaningful. Designing appropriate studies is a constant and dynamic process of education, renewal and improvement that everyone has to go through, so if you’re just starting to get involved as a clinical trial investigator, what I would recommend is this: embrace the learning process and get started with an established industry-sponsored trial. It gives you an appreciation of how complicated it is to run a clinical trial. There are so many study design and compliance issues that an investigator needs to be aware of before setting out on their own to design and enroll a clinical trial. And, I have been there: by getting involved in the photodynamic therapy trials for neovascular AMD, I learned a tremendous amount that gave me the experience I needed to move forwards and look at anti-VEGF therapy and the role of OCT imaging.

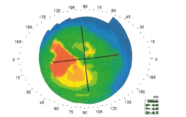

Another piece of advice is to be prepared to pivot and go where the research takes you. Don’t be so fixed in your idea and approach that you are not going to learn from what you – and others – are doing. About six years ago, I pivoted and decided to investigate dry AMD, and I realized that we didn’t have endpoints or imaging modalities that could give us more reliable quantitative measurements about disease progression, so I have spent a number of years using spectral domain and swept source OCT to come up with clinical trial endpoints that we can employ in dry AMD trials (1).

In my view, it is essential that we develop endpoints that can be used at earlier stages of AMD, and we propose to focus on intermediate AMD through using drusen volume as a predictor of disease progression (1). In November 2016 there is going to be an important meeting involving the NEI, ARVO, and the FDA focusing on clinical trial endpoints for dry AMD, and I hope that we are able to reach a consensus on how best to design and conduct these trials to test novel therapies that we so desperately need.

- KB Schaal et al., Ophthalmol, 123, 1060–1079 (2016). PMID: 26952592.

Philip Rosenfeld is Professor of Ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, Florida.