What Goes Around...

Rejuvenating cataract surgery with a simple device – miLOOP – and ensuring it reaches those who need it most

At a Glance

- We have exploited the shape memory properties of nitinol to develop a simple and efficient cataract fragmentation device in a single-use, disposable format

- The miLOOP comprises a nitinol filament mounted on a pen-type actuator, and enables rapid non-thermal cutting of even the hardest cataracts without vibrational, laser or heat energy, and with no fluidics complications

- In consequence, miLOOP cataract surgery is faster and more efficient particularly in the context of grade 3 and 4 cataracts; furthermore, low cost and ease of use make it a viable option for both emerging and developed markets

- The way is now clear to address the 25 million cases of cataract-associated blindness seen each year in the developing world, and to improve the efficiency and safety of cataract surgery in the developed world.

Microinterventional technology in surgery isn’t new; our colleagues in the cardiovascular and interventional radiology fields have been using microstents and similar devices for about 40 years. Ophthalmic surgery, however, has generally failed to benefit from these developments. But things are changing – in glaucoma, for example, we’ve seen dramatic advances associated with the advent of MIGS. Nevertheless, in cataract surgery, we’re still using the capsulorhexis and chopping tools that we were using 20 years ago. I believed that it was time to rejuvenate this field, and so I developed miLOOP – a simple, low-cost device for microinterventional cataract surgery.

A not so ‘cheesy’ idea…

In the San Francisco Bay Area (with its proximity to Napa Valley), some of the best ideas come over “wine and cheese,” as was the case with miLOOP which was conceived over a glass of wine and some hard, well-aged, aromatic cheese... How do you cut through hard cheese? You don’t use a knife (nor a phaco machine) – you use a cheese wire. So, why not cut cheddar-hard cataracts the same way?! When we discussed with the engineers, we saw immediate advantages to this approach; no cumulative dissipated energy; no fluidics complications; and no phaco machine creating a centrifuge in the eye!

Over time, we slowly figured out how to make the concept a reality. The basic technology – superelastic, memory-shape nitinol – already existed, so the big challenge was applying the technology to the specific demands of the eye (using wire to cut the lens without tearing its four µm capsule is not straightforward). Indeed, the idea was so high risk that, when I formed Iantech to develop the concept, I didn’t even try raising money at first and instead funded the initial development myself.

I was fortunate to partner with Luke Clauson, an engineer who has developed many interventional devices in the cardiovascular field, and, along with his team, we devised a workable device. In brief, miLOOP comprises a memory-shaped, thin micro-filament capable of loop conformations, mounted in a pen-type actuator (Figure 1). We finalized a working design in only a few months – and, amazingly, we have not needed to change it.

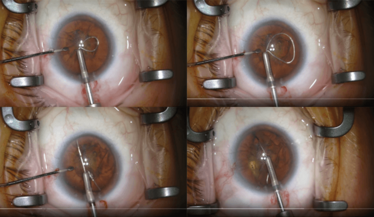

Essentially, the miLOOP does all the work for the surgeon by unfolding and refolding into the memory shape conformations within the capsule. All the surgeon needs to do is turn it, to allow the loop to travel around the lens, and then actuate the cut (Figure 2). Seeing the wire hug the lens surface and move around it, without damaging the capsule, is almost magical. The cutting action is very gentle and efficient (watch video); contrast that with conventional surgery, where you have a phaco needle and other invasive instruments to crack the lens, and the use of centrifugal lens fragmentation (working from the inner to the outer part), which stresses the capsule. With miLOOP, the lens is cut without vibration or aggressive manipulation, and its action is centripetally directed (moving from the periphery to the center) – far less traumatic for the capsule, and far less risky for the zonules.

Tackling the tough mothers (aka Dura Madres)

How does the miLOOP perform in practice? From personal experience, I can tell you that it brings significant advantages for those cases I call ‘dura madres’ (tough mothers) – the five percent or so of cataracts that are very hard. I’ve seen many of these in international work, for example, in Ethiopia and Panama, and I know that surgeons are often ‘scared’ of them, because phaco techniques aren’t adequate. But miLOOP is cataract grade-independent: it deals with dura madres as easily as with softer cataracts. I like to say it makes an average surgeon brave and a brave surgeon more efficient! Furthermore, the device is multifunctional: it not only cuts the lens, but also sweeps and polishes. Hence, even surgeons that are comfortable with hard cataracts love miLOOP, because it helps collect peripheral debris.

Importantly, the miLOOP procedure reduces the incidence of capsular tears. The real rate of capsular tears, by the way, is higher than most people admit. In our randomized control study (1), we observed a capsular tear rate of 7.5 percent in very hard cataracts, even higher with stand-alone phacoemulsification; but when we tried to publish it in the JCRS, the journal rejected the paper as they thought this rate was too high! We educated the reviewers further by bringing their attention and referencing a UK study of over 55,000 cases, which reported an overall capsular tear rate of 2 percent, increasing to 6–7 percent in harder cataracts (2). So phaco is safe enough for soft cataracts, but far riskier in hard cataracts: with miLOOP, hard cataracts become as low-risk as soft cataracts once you complete nucleus disassembly without using phaco energy. Our randomized clinical study that compared miLOOP followed by phacoemulsification with phacoemulsification alone showed that the use of miLOOP was associated with a 40 percent reduction in cumulative dissipated energy in the eye (1). I couldn’t quite believe how much energy we can save by simply sectioning the nucleus with the microfilament. And, by the way, our study involved top-flight surgeons and the most advanced phaco machine on the market (we set the bar high!).

Another advantage of miLOOP is that it is very intuitive to use. Surgeon feedback indicates that the learning curve for the device is three to five cases; compare that with phacoemulsification, which can have a learning curve of 500 cases. The procedure is so elegant that it doesn’t require any specialized training – it can be mastered by both manual and phaco surgeons alike. In Ethiopia, for example, where we have introduced the miLOOP, they have 40 trained nurses performing the procedure. And having operated with them, I can tell you that they are very good.

Finally, the economic arguments for miLOOP are clear. People increasingly understand that femtosecond laser-assisted surgery is associated with significant costs, which may be difficult to sustain under increasing budgetary constraints. Remember, 20 years ago a surgeon would be reimbursed maybe $2,500 per cataract procedure; today, it is $700. There is a clear need to make our procedures more efficient and less costly, which implies elimination of capital equipment costs, not assimilation of additional costs. (Given this context, it seems strange that instrumentation manufacturers are continually making bigger and more complex phaco machines). On the other hand, miLOOP is a single-use device that requires no capital investment and costs about $150.

Figure 1. The pen actuator allows the nitinol loop to be inserted through a clear corneal incision and then expanded to encompass the lens. Constriction of the loop results in atraumatic, energy-free bisection of the lens, independent of cataract grade and without stressing the capsule. Loop movements have a capsular sweeping and polishing effect.

Figure 2. The miLOOP procedure. After completing a capsulotomy procedure, the miLOOP is inserted into the eye through a clear corneal incision (top left), the nitinol loop expanded (top right) and the fully expanded loop passed over the lens (bottom left). The surgeon actuates the cut and the loop constricts and cuts through the lens (bottom right). The loop is extended again, and rotated to cut the lens across a different plane. The maneuver can be repeated to cut the lens into six pieces.

Instant impact

The features of simplicity and low cost make miLOOP an ideal choice for resource-poor countries. The Gates Foundation-backed Global Health Investment Fund (GHIF) recognized the potential; when it invested in Iantech, it was the first time a device of any form had been supported. We’re very proud of that. With their help, we’ve set up a Global Access Program that allows free access to miLOOP in a demonstration program for at least three developing countries in 2018. So instead of the product ‘trickling down’ to the developed world in 20 years or so, they get access to it right now. This approach is transformational for those countries; instead of removing cataracts via a 5 mm outer incision and a 9 mm inner incision, which is pretty harsh on the eye, the patients only need to receive a 4–5 mm cut. And with next generation technology, we can be on track to go sub 3 mm. It is time to depart from the surgical technologies of the 1950s – a hook and cannula – and introduce innovation much more broadly ... and globally. The result? We can at last address the 25 million-strong backlog of cataract-related blindness in the developing world – the real benefit of working together with all vision stakeholders by enabling them through new technology which can inflect the curve in our fight against blindness.

Consider that phaco surgery hasn't dented global blindness in 40 years, but miLOOP is making a difference right now. It’s so important that previously blind people can go back to their communities, dispense with care-givers and become economically active again. You can’t put a price on that. So although we won’t make any money through the Global Access Program, we’re helping to solve an important problem, which is immensely satisfying; the profits will come when we launch the device in the developed world.

Doing it miWAY

What about the future? At present, we are working on a second-generation device called the multi-LOOP; this folds into a triple loop to simultaneously cut in x, y and z dimensions. Rather than cutting the lens into two pieces, and then into two again – as you do with miLOOP – the multi-LOOP cuts it into three and four pieces at once. Ultimately, the idea is to ‘ultra-fragment’ the lens and at the same time create a port so that fragments can be removed without the need for any phacoemulsification. We expect this system to be on the market in about 12 months, and we’re calling it miWAY. So while miLOOP simplifies cataract surgery and makes it safer, especially for difficult cases, next generation products will take the concept further by completely eliminating the need to introduce energy into the eye, both during and after fragmentation. The idea is to develop an energy-free, kit-based system that can be applied to any cataract, regardless of grade. In the future, I believe a small box containing a couple of disposable pen-like devices will be all that people need for cataract surgery.

Sean Ianchulev is Professor of Ophthalmology at New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, New York, USA.

Ianchulev reports that he is Founder and Chairman of the Board at Iantech Medical and Founder and CEO of Eyenovia.

- T Ianchulev et al., “Microinterventional endocapsular nucleus disassembly: novel technique and results of first-in-human randomised controlled study”, Br J Ophthalmol [Epub ahead of print] (2018). PMID: 29669780.

- P Jaycock et al., “The Cataract National Dataset electronic multi-centre audit of 55,567 operations: updating benchmark standards of care in the United Kingdom and internationally”, Eye (Lond), 23, 38–49 (2009). PMID: 18034196.

Sean Ianchulev is Professor of Ophthalmology, New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, New York, USA; Founder of Eyenovia, Iantech, Iantrek, KYS Vision, PME ventures.