Everybody be COOL

Sitting Down With... David Huang, Peterson Professor of Ophthalmology and Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), Portland.

You’re a co-inventor of OCT – and lauded for it. How does this feel?

Of course it is wonderful to know that this invention has been successful, useful, and beneficial to tens of millions of patients on an annual basis. I couldn’t have anticipated it at the beginning and I am very happy to see it grow over the years – the technology is always getting better and there are more diseases where it is useful.

OCT was your PhD project – at the time, did you have any inkling of how far it might advance?

Well, no! I knew there were many ways forwards. Back at the start, we thought of many ideas to make OCT faster, as we realized this was the key to making it more powerful and useful. But implementing these general ideas was challenging. I have been surprised and gratified by the number of high-caliber people who came into the field and moved it forward. A big milestone was the development of spectral domain (SD)-OCT back in 2003 – that really required deep understanding of the physics behind OCT. As a researcher, it is challenging to operate in this incredibly competitive field with so many innovative people and strong research groups. But it is also exhilarating to watch the rapid progress the field has made!

What are your thoughts on the future of OCT?

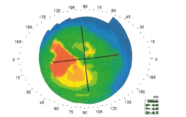

Over the next 10–20 years I think the potential lies in improving speed, decreasing cost, and making it more compact. Swept-source OCT can operate at higher speeds than SD-OCT, and once it is two or four times faster there will be a real clinical and commercial advantage despite the higher cost initially. There is also potential to put multiple swept-source systems and beams on a single chip, which would continue to improve speed and eventually decrease cost. If you are buying a system now, I don’t actually think that swept-source has a lot of advantage, but in the long run, I think it will dominate at some point.

Do you consider yourself to be an inventor?

I actually do think that’s my primary job. I am not sure where the ideas come from – the solutions just occur to me as I think about engineering and clinical problems. My clinical practice keeps me familiar with clinical problems: it lets me know what technological innovations are needed to improve clinical application or inspires inventions tailored towards specific diseases. I was able to develop disease-specific inventions because of my knowledge in ophthalmology, but others, like the angiography algorithm, came more from my understanding of the physics of light-tissue interaction.

How do you think mobile diagnostics will change the future of ophthalmic care?

I think they will be very important, especially in the ophthalmic space. When you look at a heart valve or other invasive technology, it is very hard to imagine a smartphone being involved, but if you are trying to check vision or measure refraction, a smartphone with a nice camera can do a lot. Amblyopia risk factors, myopia progression, keratoconus, retinal diseases and glaucoma – I think that these all have the potential to be followed at home through mobile devices, or by primary care physicians rather than specialists. I think this trend will continue as smartphones are getting more and more powerful, and I foresee a very important role in the future for mobile diagnostics.

What was the inspiration for developing the GoCheckKids app?

It was actually a little bit roundabout. A. Linn Murphree came to give a lecture on his work in retinoblastoma, and commented that it was “mostly for naught because often patients were diagnosed to too late to save their eyes or save their lives.” And because most cases are caught when they were having their photograph taken, I thought that we should have an app to do this and diagnose it. But retinoblastoma is actually quite rare, and what we discovered when we were photographing children is that we should be gearing this product towards amblyopia, which is much more common and an important cause of blindness in children. And there turned out to be a great need for screening children – more than 100,000 have already been screened, which is really satisfying to see.

You run the Center for Ophthalmic Optics and Lasers – the COOL lab. What can we expect to see in the next few years?

The COOL lab is special because it is a vertically integrated research group with the capability to develop advanced OCT prototypes and algorithms, and take them from the bench to multi-center clinical trials. Right now we are really focused on OCT angiography, and we hope to improve the hardware and software to advance the capabilities of wide-field angiography and reduce artifacts. We also hope to advance clinical applications by conducting clinical studies and serving as a reading center for larger trials.

What do you enjoy most about your job?

If I can have an idea for a better design of an imaging system, or a more efficient algorithm, then I feel very satisfied because we are able to take the field forward in a clever way. It is also gratifying to see other investigators pick up these ideas and further improve them. Seeing them used clinically on a wide scale is most satisfying.

Reflecting on your career so far, are there any “do’s” and “don’ts” that you would share?

In my experience, finding collaborators and clinical investigators who really care about advancing the technology and its applications is invaluable. If you do this, you really need to cultivate and help them, and share credit. The research enterprise depends on a few people who are the main driver of progress, and it is very important that those people feel valued.

As for “don’ts,” I would say don’t get stuck in a rut – it is important to learn when to quit. You have to learn to bet on the winners and fold on the losing hands, because no matter how clever you are you always end up going in some blind alleys, both in terms of teams that won’t work or projects that have low significance or are too technically difficult. Sometimes this is just a matter of timing. Like when we were trying to do swept-source in the 1990s and it was extremely difficult, but now it is making progress in leaps and bounds.

Martha and Eddie Peterson Professor of Ophthalmology and Professor of Biomedical Engineering, Associate Director & Director of Research at the Casey Eye Institute, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Oregon, USA