Surprising Associations, Surprisingly Available

Clinical records harboring useful data are there for the taking – we just need to access and analyze them

At a Glance

- Expert interrogation of large medical records databases may yield important insights into drug effects and disease biology

- From a medical insurance claims dataset, 423 drug classes (1,763 drugs) were assessed for an association with glaucoma risk (6,130 test records, 30,650 controls)

- Unexpected findings included a 26 percent higher risk of POAG associated with calcium channel blocker prescriptions, and a 30 percent lower risk associated with SSRI prescriptions

- Much can be learned from clinical databases, and findings from these studies can open the door to research novel disease pathways.

With clinical care comes patient-specific records of medication history and disease outcomes. Today, these data are better captured and curated, and more widely available than ever before – which is exciting because such information from routine clinical care can readily provide important and unexpected insights into drug effects or disease biology. Our recent investigation (1) into potential associations between glaucoma risk and systemic medications is testament to this. Our idea was to assess every medication class for its potential contribution to the probability of developing serious glaucoma. But with hundreds of drug classes to independently analyze, we needed a very large number of patient records to get statistically meaningful results.

Big ideas need big data

Luckily, my collaborators had access to (and were familiar with) the Truven Market Scan Data Set (2) - a database comprising US insurance claims from nearly 200 million patients. These records were generated through routine clinical care, and so are not as rigorous as trial data; nevertheless, they include key facts, such as which patients had glaucoma and of what type, what procedures they underwent and what medications they had been prescribed. It was exactly what we needed.

We developed a methodology (Box 1) to interrogate the Truven dataset and analyze potential associations between systemic drug use and development of primary open angle glaucoma (POAG). In brief, we matched two populations of patients – those with POAG who had received a glaucoma procedure, and patients who had undergone cataract surgery but had not been diagnosed with any form of glaucoma. We then compared prescription drug use in the preceding five years. And it was exciting! With such a large patient group, we could test all 423 drug classes yet maintain statistical validity. I felt sure that we would discover something new. And we did.

Box 1: Methodology Outline

- Analyzed US insurance claims database containing medical records for >170 million patients

- Test population: patients with POAG who had received a glaucoma procedure

- excluded: patients with other forms of glaucoma

- Control population: patients who had undergone cataract surgery without a glaucoma diagnosis

- excluded: patients with glaucoma or undergoing non-routine cataract surgery

- Alternative control population: patients with any visit to an ophthalmologist

- A total of 423 drug classes (1,763 drugs) were assessed, used in the five years preceding POAG procedure in 6,130 test patients, matched to 30,650 controls

• alternative control population: 6,269 tests matched to 43,883 controls - Association of drug use with POAG was analyzed by logistic regression using standard statistics packages (SAS, STATA and R)

• Drug classes significantly associated with POAG were separately analyzed for dose-response effect on POAG risk

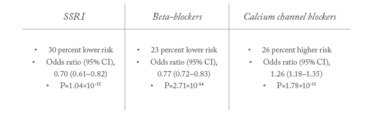

Table 1. Top three drug classes significantly associated with POAG risk

Surprise, surprise

One of the clearest signals we identified was an association between beta-blocker use and reduced glaucoma risk – an effect known since the 1960s and caused by the ability of systemic beta-blockers to lower IOP. We were pleased to find this, as it was rather like an internal control, proving to us that our model was working. But another observation really caught our attention; although a number of associations were evident (Table 1), two drug classes stood out in particular.

Firstly, we found a strong association between calcium channel blocker prescriptions and increased POAG risk; the scale of the increased risk (26 percent) was remarkable, and the statistical significance very high (P=1.8×10-11). Previous studies have hinted at a possible link between calcium channel blockers and glaucoma, but never revealed a consistent association. To find such a strong signal was therefore completely unexpected. Secondly, we found an even stronger and larger-scale association between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and decreased POAG risk; the protective effect for SSRI users is ~30 percent as compared with non-users, and the statistical significance is even higher than for calcium channel blockers (P=1×10-15 and P=6×10-24 in analyses based on the alternative control population). We also found a marked dose-response effect: longer SSRI use was associated with a progressively lower risk of having a glaucoma procedure.

As we only have observational data at this stage, we cannot be certain of a causative relationship between drug use and altered POAG risk. In theory, the increased risk associated with calcium channel blockers could instead be caused by the high blood pressure – the symptom the drugs are prescribed to treat, rather than the drugs themselves. However, this seems unlikely, as our analysis indicates that ACE inhibitors – the commonest antihypertensive class in the study – showed no significant association with glaucoma risk. Similarly, we found no association between POAG risk and anti-depressive classes unrelated to SSRIs (such as tricyclics). A separate statistical analysis revealed no association between depression diagnosis and POAG risk. Therefore, it is possible that the protective association observed with SSRIs is a function of drugs that interfere with serotonin reuptake. Another theoretical possibility is prescribing patterns: for example, physicians may be less likely to prescribe SSRIs for POAG patients. But our finding of a clear correlation between increasing SSRI use and progressively lower risk of POAG counteracts any role played by prescribing patterns. At this stage, the associations between particular drug classes and POAG seem to be genuine.

What’s going on?

Right now, we’re not sure what our findings mean – but we know they merit further investigation into potential mechanisms driving disease. The SSRI association could be mediated through serotonin pathways in ocular tissues, but this is currently a poorly understood field. Serotonin receptors are expressed in retinal ganglion cells (3) – but also in the iris and ciliary body. Some have suggested that serotonin pathways affect pupil diameter, which then contributes to glaucoma risk. And there is also some evidence that serotonin receptors may directly affect IOP (4). Getting to the bottom of serotonin’s role in ocular biology will be a fascinating journey.

The mechanisms driving the calcium channel blocker association also require some unraveling given that both low blood pressure and hypertension diagnosis are associated with increased glaucoma risk (5). There is evidence that the higher risk of glaucoma with lower blood pressure is only seen in patients receiving antihypertensive treatment (6); it is possible that the increased risk is not due to low blood pressure per se, but due to other effects on the optic nerve by specific antihypertensives such as calcium channel blockers. The relationship certainly needs investigating because hypertension is a common comorbidity in glaucoma, and so many patients are taking calcium channel blockers – in fact, Japanese physicians sometimes prescribe these drugs to protect against glaucoma...

What next?

Although clinical practice shouldn’t change because of our findings, we do think our data reveal important information and interesting hypotheses to explore. One of our imminent next steps is to repeat our work using another dataset, such as the UK BioBank. If the associations still hold in an independent data set, it warrants further work; we must establish the biological basis of the effect – for example, by investigating whether these drugs can modulate glaucoma risk in animal models.

Our findings could also guide fundamental research into disease mechanisms; for example, the role of serotonin pathways in glaucoma etiology. POAG is complex and multifactorial; certainly, IOP is not the whole story, as high IOP patients don’t always get glaucoma, and low IOP patients sometimes do. As we still don’t understand much of the biology that underlies this disease, we need new hypotheses. And datasets, such as the one we investigated, could suggest specific avenues to explore.

Currently, we are investigating the relative risk associated with different calcium channel blockers. We are also examining associations between systemic medications and relevant ocular features, such as cup-to-disc ratios. More generally, there is still so much to do with datasets like Truven. I think we are ‘missing a trick’ because nobody has investigated associations between systemic medications and macular degeneration or diabetic retinopathy. Given that patients with these conditions are older and more likely to be receiving systemic medications, we really need to understand how different drugs might affect disease progression and response to medication, or even to surgery. Database ‘mining’ can really help this kind of investigation, and can generate novel and surprising discoveries. It’s also a very cost-effective approach: interrogating existing records doesn’t incur the costs associated with getting informed consent from – and running tests on – each of several hundred new patients. The data is already available. We just need to take more advantage of the new insights available to us.

Anthony Khawaja is a Consultant Ophthalmologist at NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Moorfields Eye Hospital and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, London, UK.

- W Zheng, et al., “Systemic medication associations with presumed advanced or uncontrolled primary open-angle glaucoma”, Ophthalmology, in press. (2018).

- Truven Health MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Insurance Databases, Truven Health Analytics, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

- S Hidaka, “Serotonergic synapses modulate generation of spikes from retinal ganglion cells of teleosts”, J Integr Neurosci, 8, 299-322 (2009). PMID: 19938208.

- C Costagliola, et al., “SSRIs and intraocular pressure modifications”, CNS Drugs, 18, 475-484 (2004). PMID: 15182218.

- D Zhao, et al., “The association of blood pressure and primary open-angle glaucoma: a meta-analysis”, Am J Ophthalmol, 158, 615-627 (2014). PMID: 24879946.

- A Harris et al., “Association of the optic disc structure with the use of antihypertensive medications: the Thessaloniki eye study”, J Glaucoma, 22, 526–531 (2013). PMID: 22411020.

Anthony Khawaja is a Consultant Ophthalmologist at NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Moorfields Eye Hospital and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, London, UK. In 2017, Khawaja was voted #8 on The Ophthalmologist Rising Stars Power List.