The Retina, Renewed… Thanks to Your Own Skin Cells

Might you soon take a skin cell from a patient with retinitis pigmentosa, roll it back to a pluripotent state, culture it to become retinal cells and trial gene therapy on it in vitro?

Personalized medicine is a particularly hot topic in medicine. Take cells from a patient, modify or grow them, and return them to the patient for their therapeutic effects. What a team of Manhattan-based researchers are doing at the Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) is something rather special. They take skin epithelial cells from patients with retinitis pigmentosa (RP), turn them into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, then differentiate them into retinal cells in cell culture, enabling them to examine what the structural and functional defects of these retinal cells really are – without having to perform a dangerous (and ethically dubious) excision of a section of a patient’s retina to do so (1).

More than 60 different genes have been linked to RP, making it a challenge to go to a mouse model to study the disease. Making a genetically-modified mouse is time consuming enough, but there’s the additional confounding factor that the retinae of mice and men have enough interspecies differences to induce a great depression in researchers. This is why the ability to study the patient’s own retinal cells in culture is so valuable.

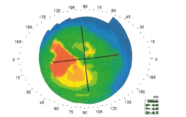

Using this approach, the CUMC researchers examined cells from a patient with RP that resulted from a mutation in the MFRP (membrane frizzled-related protein) gene. Analysis of these cells showed that the primary effect of MFRP mutation is to disrupt the regulation of the major cytoskeletal protein, actin (Figure 1). “Normally, the cytoskeleton looks like a series of connected hexagons,” said lead researcher, Stephen Tsang. “If a cell loses this structure, it loses its ability to function.”

In the next phase of the study, the CUMC team used adeno-associated viruses to introduce normal copies of MFRP into the iPS-derived retinal cells (in cell culture), successfully restoring the cells’ function. The team went on to successfully use gene therapy to rescue the “normal” phenotype in mice with MFRP mutation-induced RP.

Figure 1. a. Normal (wild-type) retinal cells: the protein actin forms the cell’s cytoskeleton, creating an internal support structure that looks like a series of connected hexagons; b. This structure fails to form in cells with MFRP mutations, compromising cellular function; c. Diseased retinal cells, when treated with gene therapy to insert normal copies of MFRP, have normal-looking cytoskeletal structures and function.

Does this herald a future of personalized medicine, where patients can have their retinae reproduced from skin cells, their disease state assessed, and potential gene therapy options trialled, all in vitro, in order to choose the most effective gene therapeutic option? Tsang believes so, concluding that, “The use of patient-specific cell lines for testing the efficacy of gene therapy to precisely correct a patient’s genetic deficiency provides yet another tool for advancing the field of personalized medicine. iPS cells can help us determine whether these genes do, in fact, cause RP, understand their function, and, ultimately, develop personalized treatments.”

- 1. Y. Li, W.-H. Wu, C.-W. Hsu, et al., “Gene Therapy in Patient-specific Stem Cell Lines and a Preclinical Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa With Membrane Frizzled-related Protein Defects”, Mol. Ther. Epub ahead of print (2014). doi:10.1038/mt.2014.100.

I spent seven years as a medical writer, writing primary and review manuscripts, congress presentations and marketing materials for numerous – and mostly German – pharmaceutical companies. Prior to my adventures in medical communications, I was a Wellcome Trust PhD student at the University of Edinburgh.