Overcoming the Mountain of Global Blindness

The story behind the Himalayan Cataract Project – the NGO eradicating blindness, one country at a time.

At a Glance

- The Himalayan Cataract Project (HCP) was co-founded by Geoff Tabin and Sanduk Ruit in 1995

- Aiming to tackle avoidable blindness, the organization began its work in Nepal and has since expanded throughout South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa

- Geoff Tabin tells the story of setting up HCP, and how it all began with a philosophy degree and conquering the world’s highest mountain

- Tabin also shares his view on how worldwide blindness can be eradicated.

Nepal is the only large, low to moderate income country in the world that has reversed its incidence of blindness, and I’m proud to be part of the reason why. Back in 1995, I co-founded the Himalayan Cataract Project (HCP) with Nepali ophthalmologist Dr. Sanduk Ruit. When we started, there were more than 250,000 people bilaterally blind from cataracts in the Himalayas, with 60,000 more people going blind every year. Nepali surgeons were performing a few thousand cataract surgeries a year, but even fewer were being performed in Tibet, northern India, West Bengal, Sikkim or Bhutan. Today, the number of cataract surgeries performed in Nepal has risen to more than 350,000 a year. Where once, nearly one in 100 people were blind, the figure now stands at less than three per thousand – the same as the West. And all it took was a five-minute procedure.

If the poorest country in south Asia can eradicate preventable blindness, others can too. By establishing a top-to-bottom system based on compassionate capitalism – where paying patients subsidize surgery to keep costs low – it is possible to provide a high standard of care in even the poorest places. That’s what HCP is all about. We empower local people to take control of their healthcare. We train doctors, nurses and technicians at every level, from the primary health care workers to a subspecialty trained ophthalmologists. We know surgeons in developing countries are constrained by lack of equipment, so we try to make sure our partners are as well-equipped as possible.

In the beginning…

HCP came about almost by chance. Back in my early 20s, I was lucky enough to receive a Marshall Scholarship to study philosophy at Oxford University in the UK. At that point, I’d already been accepted to medical school in the US. If it weren’t for the scholarship, I would probably be an orthopedic surgeon somewhere doing sports medicine. My time at Oxford gave me time to think about what I wanted to do, and I became interested in the moral paradigm behind healthcare delivery, and the disparity in access to healthcare between countries around the world.

Oxford had a number of endowed funds, including the A C Irvine Travel Fund that provided resources for students to enjoy a strenuous mountaineering holiday abroad. I had always been sporty. I played university tennis and skied from an early age, but I became fanatical about climbing. With the help of the fund, I more or less spent half the year on a paid climbing holiday, scaling big walls in Afghanistan, New Guinea and Africa. The opportunity to climb in Asia and Africa allowed me to witness firsthand the consequences of extreme poverty on health, and the disparity in healthcare systems throughout the world.

My focus was already on global health by the time I matriculated at medical school. As it turned out, I wasn’t done with climbing just yet. I was asked to join the first American climbing expedition to Tibet. Together, we would attempt the last unclimbed face on Mount Everest. How could I say no?

I was applying for leave of absence from medical school when I got the phone call that would change everything. After making sure I was Geoff Tabin, the man on the other end said, “You’re probably the dumbest person ever accepted into Harvard Medical School.” His name was Dr. Michael Wiedman, and he was on the committee reviewing request for leaves of absence. “There’s no way that you would ever get a leave of absence to go climbing,” he said. “Anybody with the intelligence to get into this school should know that if you apply to do research, Harvard will give you credits.” It turned out he was interested in the effects of high altitude on retinal physiology, specifically high altitude retinal hemorrhaging as a prognosticator of cerebral edema. He said: “Let’s forget about your leave of absence and talk about our research project.” So we did.

Climbing high

In 1983, while researching under Wiedman, my team and I made the first successful climb of the east side of Everest. It’s still the only route done with only local support. It’s very technical – more than any other path up the mountain – and it’s never been repeated.

After finishing medical school, I had the opportunity to work as a general doctor at one of the hospitals in Nepal that Sir Edmund Hillary, one of my heroes, had established. Many of the problems I faced were public health issues, problems of poverty. I watched children dying of diarrhea and pneumonia and things that would be so easy to treat in the Western world. Then I saw Dutch ophthalmologist Dr. Jan Kok and his team perform cataract surgery. It was mind-boggling. Before they came, blind people just waited to die. They accepted that you get old, your hair turns white, your eyes turn white, and then you die. In an agrarian economy like Nepal, blindness was a burden for the whole family. Often children would leave school to take care of a blind parent or grandparent. But all it took was a small operation to bring these people back to life. I’d never seen anything in medicine ignite such unbelievable joy. It’s hard to express the happiness that a totally blind person feels when they are able to see again.

I knew I could make a difference. I wanted to teach people to perform cataract surgery and immediately sought a residency in ophthalmology. What I didn’t know then was that the real genius behind anything that I’d be able to accomplish in the future was also in Nepal – my HCP co-founder Sanduk Ruit. Sanduk grew up in a hill village in Nepal four days’ walk from the nearest road, with no electricity or running water. At eight years old, his father walked him all the way to Darjeeling, India to attend school. He went on to graduate with top honors and won a full scholarship to one of the best medical schools in India.

Upon seeing the level of blindness in his home country, he re-trained as a micro surgeon in the Netherlands with Jan Kok – the same doctor I saw perform cataract surgery in Nepal – and also completed a fellowship in Australia with Dr. Fred Hollows. It was the late 1980s when he returned to Nepal.

At this time, even the least expensive IOLs were cost-prohibitive for the developing world. Sanduk had the genius to team up with his mentor Fred Hollows and his eponymous foundation to raise the funds to start the first low-cost IOL factory in the world, in Kathmandu, instantly reducing the cost of the lenses from $200 to $4. In doing so, he transformed the economy of global cataract surgery – a procedure that would cost $3,000 in the United States now cost $20 in Nepal.

I heard Fred Hollows lecture in the second year of my residency. I was so impressed by him that I decided to do my corneal fellowship in Australia. Unfortunately, Fred died of cancer before I had chance to start, so I ended up doing my fellowship under Dr. Hugh Taylor, the world authority on river blindness and trachoma. It wasn’t until my fellowship that I met Sanduk and everything began to fall into place. He had already set up this amazing system of delivery, taking the best cataract care in India and applying it to Nepal. I was blown away. I finished my fellowship and moved to Nepal to work with Sanduk. That’s when HCP was born.

Going above and beyond

During our first cataract outreach together, we restored sight to 224 people in three days. Sanduk did 201 surgeries, while I did 23. The results were incredible. About 80 percent of our patients could see well enough to be able to pass the American driving test one day after surgery. With Sanduk’s cataract outreach system, a single doctor in Nepal can provide more than 100 sight-restoring cataract surgeries in a single day.

Unfortunately, people in rural Nepal didn’t know they could have their sight restored – they had to be told. And so our mission transformed. Instead of simply teaching doctors, we created an entire system of care. We established primary eye care centers throughout the hills of Nepal, which referred patients to larger regional cataract centers. We expanded upon our now full-service tertiary eye hospital, the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology, in Kathmandu. Sanduk also had the brilliant idea of introducing training programs for nurses, ophthalmic assistants, ophthalmic technicians and residents – making us the first hospital in Nepal to develop a full ophthalmology residency program.

On the move

Today, our work is no longer limited to the Himalayas despite our name. We run training sessions throughout the developing world – from Asia to sub-Saharan Africa. We currently have programs in Ghana, Ethiopia and Rwanda, and initiatives in Tanzania. One of the biggest problems in Africa is access to care. There are no neuro-ophthalmologists or uveitis specialists in East Africa – or West Africa, for that matter. In Ethiopia, there’s one ophthalmologist for every 1,000,000 people – and even that figure is deceptive. Of the 130 ophthalmologists in the country of 105,000,000 people, 30 are either working with NGOs or not doing active surgery, while 60 live in the capital, Addis Ababa, which leaves 40 ophthalmologists to serve the rest of the population – several million people each. You don’t have to be a mathematician (or ophthalmologist) to know those numbers aren’t good.

To that end, our Ethiopian training program is geared towards high-volume cataract surgery, equipping doctors with the necessary skills and equipment to deal with 1,000 cases a week. As in Nepal, we are still having to reach out to patients. And although this works for now, we are working with local partners and the Ministry of Health to establish permanent healthcare sites to make truly lasting change.

HCP doesn’t just visit a place, perform a few surgeries, then leave. We want to make a lasting impact, and we do that by finding partners. We give them the resources they need to do things on their own. We build their skills, provide them with equipment and never show them anything they can’t replicate themselves. Talented individuals often go abroad to get a better income, but Sanduk has been incredible at identifying young people who are passionate about staying in their own country. In fact, we’re currently in the process of providing fellowships in India, Nepal and America for promising ophthalmologists.

And it’s a good thing we are, because the need for comprehensive eye care continues to grow. In India, the standard of cataract care has become so great that the upper middle class are now paying for surgery before they lose their sight – leaving the destitute blind behind. To understand why that is such a huge problem, think of it on a global scale. If we were to only operate on blind people, we would need to perform about 16,000,000 cataract surgeries. But if we were to operate at the 20/100 level, it’s suddenly 60,000,000. And of those extra 44,000,000 people, many have the means to pay. Imagine if we start operating at the level we do in America, 20/60, or England, 6/18 – that number would be eight times higher. Now think of India again. There are many people who have a little trouble seeing their computer or driving at night, and they’re willing to pay to make that go away. Paradoxically, as the quality of surgery has improved, less of the surgery is going to the blind.

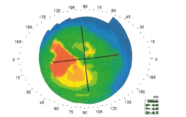

When we started out in Nepal, about 80 percent of blindness was due to cataracts. It meant if your dad was blind, you carried him for two days to see a facility and four out of five times he would come back with his sight. Those are pretty good odds. Good enough that people will come back and actively seek care. But if we played out that same scenario in Africa, things would be different. The continent has more glaucoma, more infectious blindness, and more retinal blindness than Nepal. Even people with cataracts often have glaucoma or corneal scarring from trachoma. Suddenly, the odds of a miracle aren’t so high. Half of the people who take two days off from work to carry dad to the doctor won’t get cured. Walking another two days home to hungry kids and a father who is still just as blind as he was when you left doesn’t incentivize you to proactively visit the clinic. So that’s what we’re working on right now, a way to transpose and develop a sustainable system of care to the poorest of the poor.

Still climbing

The goal may appear to be unreachable, but the truth is that there are very few public health problems we can’t overcome. Blindness can be reversed – it happened in Nepal, it happened in Bhutan, and it can happen elsewhere too. All we need is funding. We could eliminate avoidable blindness on the planet for the cost of what America spends every month on war. Just think about that – two and a half billion dollars could restore sight to every single person who is blind from cataracts. It would take $100,000,000 to change the arc of blindness in Africa. Our website, which we got by luck, is cureblindness.org – and that’s really what we’re trying to do. Help us do it. If you are interested in being part of the Himalayan Cataract Project by donating your time or money, email [email protected]. Together, we can do great things.

Geoff Tabin is co-founder of the Himalayan Cataract Project and a Professor of Ophthalmology and Global Medicine at Stanford University, CA, USA.