Navigating the Long Road

How lessons learned from a uveal melanoma cluster may present a roadmap for a team approach – and how ophthalmologists can ensure optimal care for patients

At a Glance

- Uveal melanoma is a systemic illness that requires long-term monitoring and care

- Ophthalmologists play a pivotal role in multidisplinary teams for the short- and long-term care of patients with the disease

- Ophthalmologists can further aid patients by understanding the advancements that are currently being made in uveal melanoma and metastatic uveal melanoma

- Lessons learned in the Huntersville North Carolina uveal melanoma cluster may present a roadmap for a care-team approach to the disease.

In 2014, the small town of Huntersville in North Carolina garnered international attention after a news station revealed that the town of 50,000 was experiencing an unusually high number of uveal melanoma cases. For an exceedingly rare disease – which generally has a prevalence of six to eight people out of every million per year (1) – the 12 cases found in the town over a 10-year period certainly raised concern. After securing $100,000 in state grants, local legislators were able to assemble a panel of experts – including ophthalmologists and oncologists – at the University of North Carolina, Duke University and Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, to analyze this ocular melanoma cluster, and determine how best to offer patients the treatment and support they need.

Ultimately, the disparate nature of these cases helped bring to light the challenges of ensuring that patients with uveal melanoma – who often have a lengthy disease progression – have access to appropriate immediate and long-term medical care. Most significantly these events have reinforced the pivotal role ophthalmologists play in their patients’ short- and long-term care – and the importance that all ophthalmologists remain abreast of the latest and upcoming treatment options for patients with uveal melanoma and metastatic uveal melanoma.

Understanding uveal melanoma

Uveal melanoma is the most commonly diagnosed intraocular malignancy in adults. In most cases, it develops from the pigmented cells of the choroid, but it can also develop from the pigmented cells of the iris and ciliary body. In general, uveal melanoma presents most commonly in older patients, with a higher incidence in men (2). The Huntersville cluster bucks this trend. Among the initial 12 identified individuals, nine were female and six were younger than 30 when they were diagnosed.

Uveal melanoma has an overall mortality rate of about 50 percent. The initial diagnosis of uveal melanoma generally falls to an optometrist or ophthalmologist when a patient presents with blurred vision or flashes of light. The tumor may also be found during a routine dilated exam and the patient may have no symptoms. Many assume that once a diagnosis is made, a patient is referred to an oncologist, who undertakes any future care. The reality is that because uveal melanoma is so rare, a patient who has been diagnosed with the cancer may have to travel 100 miles or more to work with an ocular oncologist who is familiar with the illness. Once treatment of the primary tumor is complete, surveillance for metastatic disease may be variable. Many patients prefer to be monitored close to home. Some will educate themselves about their risks for metastatic disease through advocacy organizations, such as the Ocular Melanoma Foundation (OMF). Unfortunately, many patients will mistakenly believe that once the tumor – which was localized to the eye – is treated that they are cancer-free and no longer need to see an oncologist. But nearly half of all patients who develop uveal melanoma will go on to suffer from metastatic disease (1). In some cases, patients may not experience progression of the disease for as many as 15 years after the initial diagnosis (3). Anecdotally, care teams who provided initial treatment to uveal melanoma patients report that they often don’t hear that a patient had developed metastatic disease and passed away until years after. Not only does this leave care teams wondering whether the patient received regular monitoring, but it also keeps clinicians from gathering vital data that can help improve care for other patients – an essential step for a cancer as rare as uveal melanoma.

As uveal melanoma is a systemic disease rather than just an ocular one, it is crucial to surround patients with a multidisciplinary team (MDT) of clinicians – including an ophthalmologist and a medical oncologist – to monitor and treat the patient over the long-term. In urban areas, these teams may be conveniently working at the same hospital – as they are at the University of North Caroline and Moffitt Cancer Center – and so may meet patients and discuss treatment strategies together. But patients in more rural areas may rely on their local hometown ophthalmologists who they see on a regular basis to help them understand their treatment options and assess next steps. For these patients, MDTs may need to come together from unaffiliated institutions and meet electronically. In either case, it is critical for all team members to understand the diagnostic and treatment options available to a patient, and ophthalmologists – regardless of specialty – play a pivotal role in the care of patients.

Approaches to treatment

Patients who present with primary tumors can often be successfully treated with local radiation therapy and ablative treatments. Depending on the size and location of the melanoma, it might be possible to retain some vision using these treatment approaches. For large melanomas, enucleation is the preferred approach, but some physicians have achieved fairly good results and comparable survival rates treating them with proton beam radiation therapy (4).

But given that approximately one out of every two patients will go on to develop metastatic disease – the leading cause of death among patients with uveal melanoma (5) – treating the primary tumor is only the first step, and patients require routine surveillance to monitor for tumor spread. Metastatic uveal melanoma often involves hepatic metastases, which can occur in as many as 93 percent of patients with metastatic disease (6). Median survival after liver involvement is poor, often ranging from 4 to 6 months, with a one-year survival of only 10-15 percent (5). Surgical resection, however, offers limited success because of the classic miliary spread of the metastases in the liver. In fact, only a small number of patients have enough healthy liver tissue uninvolved by tumor remaining for this to be an option, which is why effective therapies are crucial. Although several treatment options have come to market in recent years and improved overall survival of patients with metastatic cutaneous melanoma (such as ablation, embolization, targeted therapy and immunotherapies) (7), the treatment landscape for metastatic uveal melanoma has remained relatively unchanged. The lack of effective therapies has resulted in a poor prognosis for patients.

Fortunately, recent advancements have been made in the treatment of primary uveal melanoma, as well as the detection and treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma, which could potentially offer new options for both patients and the extended medical team managing care. Here, we overview just some of the options that are currently under investigation.

AU-011 for primary uveal melanoma

AU-011 is an investigational therapy for the primary treatment of uveal melanoma. The therapy – in development by Aura Biosciences – requires an intravitreal injection of a novel recombinant papillomavirus-like particle (VLP) that selectively binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the surface of the tumor cells, and is conjugated to a phthalocyanine photosensitizer, IRDye 700DX (8). When activated by a near-infrared light, IRDye 700DX produces reactive oxygen species that disrupt the membranes of bound cells, inducing tumor necrosis.

In a preclinical study, treatment with AU-011 yielded extensive tumor necrosis in a rabbit xenograft model of uveal melanoma; three out of 10 animals experienced complete tumor response after treatment with activated AU-011 (9). AU-011 shows high affinity for tumor cells while not binding to healthy epithelium, and so should selectively destroy uveal melanoma cells while sparing the adjacent retina; in a rabbit orthotopic model, tumor treatment was found to spare the retina and adjacent ocular structures (10). Phase Ib trials commenced in 2017 and are expected to enroll a total of 12 patients. Although clinical development of AU-011 is early and the treatment is currently experimental, should it prove effective in targeting primary uveal melanoma, it could become a valuable primary treatment option for patients whose disease is identified early.

Detecting metastatic potential

Though it has not been clinically proven, it is believed that if metastatic disease could be diagnosed early – and thus tumors treated when they are smaller – it could improve long-term survival of patients with metastatic uveal melanoma (10). DecisionDX-UM (Castle Bioscience), a gene expression profile test available since 2009, and the follow-on DecisionDX-PRAME test, which was launched in 2016, were designed with early diagnosis in mind.

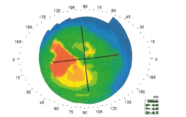

The DecisionDX-UM test evaluates the expression patterns of 12 select genes in tumor samples, as well as three control genes shown to be unchanged in uveal melanomas (11). Based on the results, tumors are classified as Class 1A (low risk), Class 1B (intermediate risk) or Class 2 (high risk). Clinical studies have shown the test is 97 percent successful in determining whether patients fall into Class 1 or Class 2 (12). But although Class 1 tumors are lower risk, metastatic disease is still a possibility. To address this, DecisionDX-PRAME was developed. PRAME – or preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma – is a cancer antigen gene that can be increased in some types of cancer. A study published by researchers at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute showed PRAME to be a strong indicator for metastatic disease in patients who had been previously classified as having Class 1 uveal melanoma (13).

Not all patients will want to undergo this type of genetic testing, but such information adds an important element to the management of patients. Current guidelines recommend that low-risk patients receive a systemic work up every 6 to 12 months, whereas high-risk patients should receive a work up every 3 to 6 months.

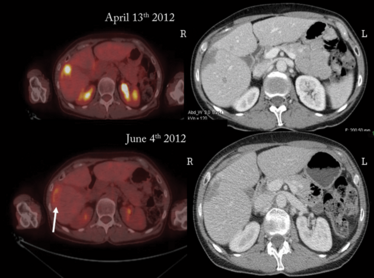

Patient before (top) and after (bottom) PHP treatment with melphalan hydrochloride. The white arrow shows the hepatic metastasis after treatment. Credit: Jonathan Zager.

Adjuvant therapy to stave off metastatic disease

In recent years, researchers have started looking at whether cytotoxic and immunotherapy regimens – both alone and in combination – could be applicable as adjuvant therapy in patients shown to be at high risk for metastatic disease.

Currently, several clinical trials are underway in the USA to evaluate adjuvant therapies. One such Phase II trial, occurring at Thomas Jefferson University in Pennsylvania, is evaluating the use of sunitinib malate or valproic acid to prevent metastasis of uveal melanoma (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02068586). Sunitinib malate is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that may prevent metastatic progression through inhibiting c-Kit and receptors, including VEGFR (14). Valproic acid is a histone deacetylase inhibitor that may lower the risk of metastasis by altering the gene expression profile in uveal melanoma cells (15). Another Phase II trial, led by Columbia University, is recruiting patients at five different centers on the East Coast and in the Midwest, and is investigating crizotinib as an adjuvant therapy for uveal melanoma (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02223819). Crizotinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is currently approved for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer, has been shown to significantly reduce metastasis in a murine model of metastatic uveal melanoma (16). Other strategies being investigated as adjuvant therapies include dacarbazine and interferon-alfa (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01100528), ipilimumab and nivolumab (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01585194) and a dendritic cell vaccine (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00929019). With these trials in early stages, use of adjuvant therapies for uveal melanoma is still several years off.

Liver-directed therapies for metastatic disease

Once uveal melanoma has metastasized to the liver, a limited number of treatment options are available – particularly for those diagnosed at an advanced stage. As such, liver-directed therapies are in use and under investigation, including embolization and percutaneous hepatic perfusion (PHP). Embolization involves the targeted destruction of tumor cells through radiation or chemotherapy, whereas PHP is a targeted whole organ therapy for the liver. The PHP procedure is a three-step process that i) isolates the liver from the circulatory system, ii) administers a high dose of chemotherapy for 30 minutes before iii) filtering out the chemotherapeutic agent from the blood exiting the liver to reduce systemic exposure and minimize many of the side effects inherent to the drug. PHP is a minimally invasive procedure that is repeatable, with patients being treated as many as eight times in early clinical trials.

A retrospective analysis comparing liver-directed therapies has demonstrated that radioembolization with yttrium-90 (Y90) and chemoembolization had a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 54 days and 52 days, respectively (17). By contrast, PHP with melphalan hydrochloride (Delcath Melphlalan/HDS) demonstrated a significantly higher PFS of 245 days (P=0.03 versus Y90 and chemoembolization). Median overall survival with PHP was also longer at 608 days compared with Y90 (295 days) and chemoembolization (265 days) (P=0.24). An even more recent retrospective analysis of outcomes data of patients with metastatic uveal melanoma has further supported the potential of PHP with melphalan hydrochloride (18). The largest study conducted to date, the analysis included 51 patients who received a total of 134 treatments. Of those, 49 percent achieved a partial (43.1 percent) or complete hepatic response (5.9 percent). The disease stabilized for at least three months in 33.3 percent of patients. Median overall PFS and hepatic PFS was 8.1 and 9.1 months respectively, with median overall survival of 15.3 months. The Moffitt Cancer Center is the lead site in the US for the Phase III clinical trial of Delcath Melphalan/HDS, with select trial sites throughout the US and Europe also involved and actively enrolling patients (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02678572). If the treatment receives approval, it could represent a huge step forward in the treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma.

Traveling the long road together

Uveal melanoma can be difficult to treat, especially when it progresses to metastatic disease. Thankfully, new advancements are in development or on the market that might help the fight against the disease. But for these advancements to make a meaningful impact on the long-term survival of patients with uveal melanoma, the care communities (oncologists, ophthalmologists and advocacy partners) must remain educated about the diagnostic and treatment options, and be vigilant about long-term patient monitoring. The key is to involve all members of a patient’s care team in the identification and treatment of the disease, as is the practice at major centers such as the University of North Carolina and Moffitt Cancer Center. The Huntersville North Carolina uveal melanoma cluster, while tragic, may become a case study highlighting the potential that exists when medical care teams work in concert. Future uveal melanoma patients in the Huntersville area have the benefit of an educated and coordinated medical community, and their long-term survival may benefit greatly.

In North Carolina, Florida and nationwide, ophthalmologists have been identified as one of the most vital players on the care team, as they are often the physician with the most sustained patient contact. As the gatekeepers to uveal melanoma patients, they are essential in identifying disease early, treating the primary tumor, educating the patient about potential options available to them and stressing the importance of ongoing surveillance. And because metastatic disease can happen years after the initial diagnosis, ophthalmologists play a critical role in reinforcing the need for monitoring and testing well after many patients may think it’s necessary. Uveal melanoma has a long treatment path – and all caregivers should be involved in making sure that patients and clinical teams stay on course.

Jonathan Zager is Professor of Surgery in the Cutaneous Oncology and Sarcoma departments, and a Senior Member at the Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA. He is also the Chair of Graduate Medical Education and Associate Chief Academic Officer. Zager is a member of the editorial board for the World Journal of Surgical Oncology and Annals of Surgical Oncology, and has published more than 220 articles and book chapters, and presented over 300 talks at national and international surgical and oncology meetings.

Kathleen Gordon is a medical director at IQVIA (formerly Quintiles) and has a volunteer faculty position at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. In addition, she serves as the president of the North Carolina Society of Eye Physicians and Surgeons. Prior to joining IQVIA, Gordon was a practicing ophthalmologist and an Associate Professor with the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She is a board-certified ophthalmologist and a Fellow of the AAO.

Disclosures: Zager reports he has received research and grant support, and Medical Advisory Board participation, for Delcath Systems.

- P Jovanovic et al., “Ocular melanoma: an overview of the current status”, Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 6, 1230–1244 (2013). PMID: 23826405.

- K Mahendraraj et al., “Trends in incidence, survival, and management of uveal melanoma: a population-based study of 7,516 patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database (1973–2012)”, Clin Ophthalmol, 10, 2113–2119 (2016). PMID: 27822007.

- F Spagnolo et al., “Uveal melanoma”, Cancer Treat Rev, 38, 549–553 (2012). PMID: 22270078.

- B Weber et al., “Outcomes of proton beam radiotherapy for large non-peripapillary choroidal and ciliary body melanoma at TRIUMF and the BC Cancer Agency”, Ocul Oncol Pathol, 2, 29–35 (2015). PMID: 27171272.

- PR Pereira et al., “Current and emerging treatment options for uveal melanoma”, Clin Ophthalmol, 7, 1669–1682 (2013). PMID: 24003303.

- Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. “Assessment of metastatic disease status at death in 435 patients with large choroidal melanoma in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS): COMS report no. 15”, Arch Ophthalmol, 119, 670–676 (2001). PMID: 11346394.

- SF Hodi et al., “Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma”, N Engl J Med, 363, 711–723 (2010). PMID: 20525992.

- R Kines et al., “An infrared dye-conjugated virus-like particle for the treatment of primary uveal melanoma”, Mol Cancer Ther, 17, 565–574 (2018). PMID: 29242243.

- PT Logan et al., “Assessment of the activity of different AU-011 doses in a xenograft uveal melanoma model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 57 (2016). Abstract 4111

- S Kaliki and CL Shields. “Uveal melanoma: relatively rare but deadly cancer”, Eye, 31, 241-257 (2017). PMID: 27911450.

- MD Onken, et al., “An accurate, clinically feasible multi-gene expression assay for predicting metastasis in uveal melanoma”, J Mol Diagn, 12, 461–468 (2010). PMID: 20413675.

- JW Harbour and R Chen. “The DecisionDx-UM gene expression profile test provides risk stratification and individualized patient care in uveal melanoma”, PLoS Curr, 5 (2013). PMID: 23591547.

- MG Field et al., “PRAME as an independent biomarker for metastasis in uveal melanoma”, Clin Cancer Res, 22, 1234–1242 (2016). PMID: 26933176.

- ME Valsecchi et al., “Adjuvant sunitinib in high-risk patients with uveal melanoma: comparison with institutional controls”, Ophthalmology, 125, 210–217 (2018). PMID: 28935400.

- S Landreville et al., “Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce growth arrest and differentiation in uveal melanoma”, Clin Cancer Res, 18, 408–416 (2012). PMID: 22038994.

- O Surriga et al., “Crizotinib, a c-Met inhibitor, prevents metastasis in a metastatic uveal melanoma model”, Mol Cancer Ther, 12, 2817–2826 (2013). PMID: 24140933.

- AM Abbott et al., “Hepatic progression-free and overall survival after regional therapy to the liver for metastatic melanoma”, Am J Clin Oncol, 41, 747–753 (2018). PMID: 28059929.

- I Karydis et al., “Percutaneous hepatic prefusion with melphalan in uveal melanoma: a safe and effective treatment modality in an orphan disease”, J Surg Oncol, 117, 1170–1178 (2018). PMID: 29284076.

Kathleen Gordon is a medical director at IQVIA (formerly Quintiles) and is a consultant to the ophthalmology practice at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Jonathan Zager is professor of surgery in the cutaneous oncology and sarcoma departments, and a senior member at the Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA.