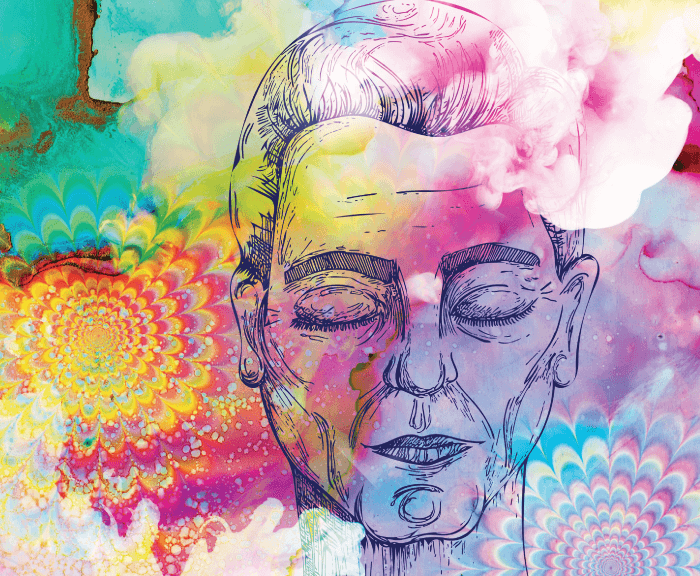

When my mother, Esme, finally confided in me about the faceless people sitting on her sofa, the gargoyle-like creature that jumped from table to chair, and the Edwardian tear-stained street child who seemed to follow her everywhere – not to mention the times the room or garden morphed into an alien place – I had absolutely no idea what could be wrong with her.

Despite advancing glaucoma, Esme lived a happy, independent life and much enjoyed completing the cryptic crossword in her daily newspaper. In that case, surely these “visions” – as she called them – were not caused by dementia? Yet, the word occurred to both of us and hung heavily in the air. With a huge stroke of luck, I discovered a tiny paragraph buried in the health pages of a newspaper about a condition that produced vivid, silent, visual hallucinations and was caused by loss of sight. It was written by a young man called Matt Harrison, but it could have been written by Esme.

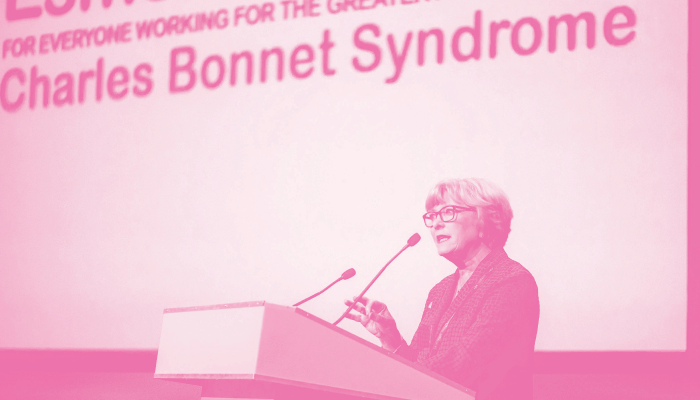

With enormous relief, I called her ophthalmologist. To my surprise, he refused to discuss CBS or tell me why he had never warned us that her diminishing sight could bring with it such a distressing condition. As I have said since – during presentations at various events – forewarned is forearmed. How could he not agree? I realize now that he probably knew very little about CBS and, possibly, thought that it would fall into a different medical specialty – even though it was caused entirely by a condition that fell into his remit. Likewise, Esme’s general practitioner (GP) had never heard of CBS, and was very skeptical about its existence. The optometrist had no knowledge of the condition, but – to be fair to him – he did become very interested when I was in a position to explain it all.

At that time, I knew nothing about Eye Clinic Liaison Officers – indeed, I suspect the Yorkshire eye clinic, which Esme attended, did not have such a person – nor Rehabilitation Officers for the Visually Impaired – and had only a vague understanding of the charities in the eye sector. With a desperate need to find some help, I was forced to do what lay people are always told not to do: I consulted the Internet. There, I found Dominic ffytche at King’s College London, who is the sole, globally-acknowledged expert in CBS. Now Reader in Visual Psychiatry, he has just been announced by Expertscape as the number one in the world for visual hallucinations of all types.

ffytche confirmed that Esme was, indeed, living with CBS, and broke the news that there were no medical specialists to whom I could take her, nor any suitable medication. He stressed that this was not a mental health issue but, for Esme, could only be treated with reassurance and coping strategies. He had developed an eye exercise which, for some people, dispelled the hallucination and, subsequently, I collected many others from the CBS community – all can be found on the website www.charlesbonnetsyndrome.uk.

I was appalled that such a disturbing yet extremely common condition could be ignored by mainstream health professionals, and only touched on during ophthalmology and optometry training. Recently, I received an email from an ophthalmologist in Canada, who had been trained in the UK. He had just read my article on CBS, and he confessed – with great embarrassment – that he was unaware of the condition and astonished that it had not featured in his training. I know that GPs in the UK receive just a few hours on ophthalmology in their course, but I had assumed that every ophthalmologist and optometrist would be aware of such a serious side effect of sight loss.

I had many questions for Dominic ffytche, and my consternation grew when he told me that CBS was not exclusive to adults: children and young people with compromised sight could develop it too (see Box: CBS in Pediatric Patients).

Although it was glaucoma that had taken more than 60 percent of Esme’s vision, CBS can be caused by loss of sight from any eye disease, including tumors, stroke, accidents, diabetes, or another condition that damages the optic nerve. It had been thought that CBS vanished after 18 months, but ffytche’s work proved otherwise.

At the time, I was writing a Health Column for The Telegraph and, determined to give the subject a wider audience, I began to include CBS along with my usual subject of cancer. I found myself inundated with emails from people who were either relieved to discover that they were not necessarily experiencing a mental health issue, were seeking more information about CBS, or just wanted to tell their stories.

It was one of these stories that persuaded me to stop hesitating, and launch an awareness campaign. The email came from a reader in the USA. She told me she had read everything I had written about CBS, and realized, to her horror, that her mother – much against the will of the family, but on the advice of the doctor – had been unnecessarily admitted to a dementia unit because she was hallucinating. No one in the unit had heard of CBS, so there was nobody to reassure her mother that the perceived worms and slugs writhing on her food and in her drink were not real. She stopped eating and drinking, with inevitable, tragic consequences. Her daughter said she would never forgive herself.

CBS Pathophysiology

Dominic ffytche, Reader in Visual Psychiatry at the Department of Old Age Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, UK

Although CBS is linked indirectly to eye disease, the underlying mechanism occurs in the brain. Visual cortical hyper-excitability is a response to reduced neural input to the visual cortex as a result of retinal or visual pathway disease or reduced light transmission within the eye (such as cataracts or corneal opacity). In neurophysiological terms, the mechanism is referred to as deafferentation; in psychological terms it is referred to as “release” – the term adopted by ICD11. Visual cortical hyper-excitability results in spontaneous increases in neural activity experienced as CBS hallucinations. Functional imaging studies capturing the spontaneous increases have shown that the visual content of a hallucination depends on the location of the neural activity: if occurring in cortex specialized for faces, the hallucination is of a face, if in cortex specialized for objects, it is of an object. Cortical hyper-excitability also leads to increased background neural activity and enhanced responses to visual stimulation. These changes are only present for patients with CBS and it remains unclear why some patients with impaired vision develop cortical hyper-excitability while others do not.

I launched Esme’s Umbrella on 16 November, 2015, at the House of Commons, with the support of The Help and Information Service (TH&IS), and with Dominic ffytche as my Medical Adviser. The date has been accepted as the official CBS Awareness Day and each year there has been a special event to mark the occasion.

Never having run a campaign of any sort (and far outside my comfort zone), I was spurred on by the torment of Esme’s final years and that of so many others to whom I was speaking on my helpline, which had been set up for me by TH&IS. Callers’ descriptions of their hallucinations were gathered by TH&IS, building up a database – until new data protection regulations (GDPR) called a halt. Last year, the call volume became so high – too many for me to answer alone – and I had to relinquish my Helpline to the Eye Health Team at the RNIB (the number is +44 (0)20 7391 3299). However, I am always happy to return calls or refer people to the CBS Buddy Helpline at Retina UK.

To mark the first year of Esme’s Umbrella, SELVIS – the eye charity in south London – offered to host an event. We were nervous about how many people would turn up – would anyone appear? The day proved that my decision to launch a campaign had been entirely correct. The room filled with people from the CBS community – many of whom had never spoken to another person with the condition and had thought they, alone, lived in a world of hallucinations. For health and safety reasons, we had to turn people away at the door. It was evident that the CBS community was hungry for information – and the opportunity to join together for a day.

Witnessing the evident delight of the group and how enthusiastic they were to help push the campaign forward, the next step I took was requested by them: to start some Esme Room Support Groups. The question was: where and how? In the end, I decided to ask all the local low vision charities around the UK to host these events, at which people living with CBS – and their families and friends – could meet over a cup of tea and exchange experiences and coping strategies. In the same way as English National Ballet’s “Dance for Parkinson’s” project has opened up a social world for people with that condition and their caregivers, my plan is for the Esme Rooms to evolve into proper CBS hubs, offering information, support and practical advice about CBS and sight loss in general. If funding allows, these hubs could also include counseling, mindfulness and free complementary therapies. Esme Room Support Groups would help inform improved social support. The Esme Rooms, which are already up and running, report great success in relieving the stress of living with CBS – for patients and caregivers.

It is not just those for whom CBS hallucinations are part of their everyday life that need support. Family caregivers describe how the intangible nature of the hallucinations – and their frequency – produce such a feeling of isolation within the relationship. They know that CBS is not a mental health condition, but having to constantly reassure someone that there is no dog, no hole in the floor or no fire, can be very wearing. It is vital that these caregivers are not forgotten.

London City University has produced a research survey for eyecare professionals: “Caring for the Carers” (1). The writers asked for my input and CBS is included. There is also a follow-up survey directly targeting caregivers themselves (2).

Though care and support for those whose lives have been affected by both sight loss and CBS was at the forefront of my campaign, it was also very obvious that I needed to begin by raising awareness of CBS across the whole healthcare profession and out in the community.

Starting with the Royal College of Ophthalmologists, I visited its President, Mike Burdon. He was hugely supportive and invited me to speak in his session at the College’s Congress in May 2018. It seems that, though ophthalmologists have always been aware of CBS, many did not appreciate how it negatively affects those who develop it and how it can impinge on relationships with family and friends.

I suspect that one of the reasons ophthalmologists have not all felt the need to offer a warning or information about CBS, was that their patients – afraid that the hallucinations heralded a mental health issue – said nothing. Or, the clinicians only heard about benign, beautiful images seen by their elderly patients and assumed, wrongly, the hallucinations were only linked to aging and macular degeneration. Consequently, it was not considered a problem. I asked Michel Michaelides, Consultant Ophthalmic Surgeon at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, if he agreed with my conclusion. He does, and adds, “Several factors may contribute, including patient stigma, timing of symptom onset, and the eye-examination focus of ophthalmology/optometry assessments.”

Michaelides is well aware of CBS, but I still find myself having to correct some ophthalmologists who are of the opinion that the condition is somewhat “fanciful.” I assure you: it is not, if you live with it. One person whose normal vision is partial and blurred, told me that he woke to find a large tiger sitting beside him. The beautiful colors of the tiger’s coat were sharp and clear – but so were the teeth and saliva.

Another problem was that CBS was not included in previous versions of WHO’s taxonomy of diseases and conditions and not mentioned by name in its recent revision. It was only referred to as “visual release hallucinations.” And that is why I began my crusade to include Charles Bonnet Syndrome as a condition in its own right. With the help of August Colenbrander, ophthalmologist and senior scientist at Smith Kettlewell Eye Research Institute in the USA, and Andrew Dick, Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Bristol in the UK, I succeeded. CBS and visual release hallucinations are now listed in WHO’s ICD 11. And that represents a huge breakthrough; the NHS has no excuse not to exact its duty of care to people living with CBS. As Andrew Dick comments: “I believe it is now timely for the NHS to recognize CBS in line with the WHO diagnostic classification. To benefit patients, an initial action would be academic – to provide evidence of the extent of the problem – contemporaneous to NHS funding to support pathways for diagnosis, treatment and support.”

ICD11 and CBS

The World Health Organization oversees the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) that provides a standardized taxonomy used by healthcare systems all over the world. Major revisions are released approximately every 20 years to reflect changes in clinical practice and disease understanding. Like previous versions, ICD 11 is arranged as a series of coded sections and subsections. Diseases of the visual system (09) contains a section Impairment of Visual Function with a subcategory for Subjective Visual Experiences. These include seven specific categories, such as visual discomfort, hemifield losses, and transient visual loss. Last on the list is 9D56 Visual Release Hallucinations with the illustrative description: “Charles Bonnet syndrome, also called visual release hallucinations, refers to the experience of complex visual hallucinations in a person who has experienced partial or complete loss of vision. Hallucinations are exclusively visual, usually temporary, and unrelated to mental and behavioral disorders.” There is acknowledgment that visual hallucinations also have other causes, with schizophrenia and primary psychotic disorders specifically excluded from the visual release hallucinations category.

Although a small acknowledgment, this represents a major advance in the recognition of CBS. The scheme used over the last two decades (ICD10) included Visual Disturbances and Blindness (H53-54) with a subsection on Subjective Visual Disturbances (H53.1), where visual hallucinations were specifically excluded. Instead, visual hallucinations were coded in the symptoms and signs involving cognition, perception, emotional state and behavior (R40-R46) as R44.1 – Visual Hallucinations, thus disconnecting visual hallucinations from eye disease and not allowing for the possibility of CBS as a clinical entity. In the version used through the 1980s and 1990s (ICD9) visual hallucinations are not even mentioned in the scheme.

GPs and hospital doctors are rarely aware of CBS. If a patient confides the reason for a broken bone – avoiding the sudden appearance of a snake, flames or a Lilliputian-sized army – misdiagnosis is on the cards. The patient is ushered down the mental health pathway, wasting clinicians’ time and medication – all precious NHS resources.

Much time and money would be saved if the NHS Falls Prevention Unit included CBS as a reason to be very careful as you move around the house. I always suggest checking with a cane to see if the image is real. Guide dogs are a great help because even the best trained dog would react if a rat ran across the room or a weary Second World War soldier appeared. Even cats – as I told one distressed caller – would not stay around if a waterfall suddenly flowed from the ceiling. However, it is not always easy to think logically at that moment.

I asked my own GP, Joanna Cheung, if she had heard of CBS. She says, “When Judith first mentioned CBS to me at the end of a routine GP consultation, I toyed with the idea of using the ‘trying to look wise with a knowing nod’ technique, but in the end confessed to knowing nothing at all about it. And that is the response from the majority of GPs. I thought it must be a rare condition (as I hadn’t heard of it), but figures show over 100,000 cases in the UK, and these are just the formally diagnosed patients.”

Actually, Dominic ffytche estimates there are one million people living with CBS in the UK. A straw poll by Renata Gomes, Head of Research at Blind Veterans, concluded that three quarters of her veterans lived with CBS – and probably more, but “stiff upper-lips” prevented them from confiding in anyone. It can only be very roughly estimated how many patients are living with the condition around the world.

As Andrew Dick says, we need proper prevalence studies. It is hard enough for children who are told that their eye condition means they will lose their sight, but if no one understands CBS and warns them, it becomes a lot harder. I suspect there are many pediatricians with no idea that the children with low vision in their care could also be living with CBS. Indeed, I was thanked by a Developmental Vision Pediatrician – who had heard me speak – for alerting her to the possibility.

CBS in Pediatric Patients

Mariya Moosajee, Consultant Ophthalmologist at Moorfields Eye Hospital and Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London, UK, on BOSU and the need for evaluation of pediatric CBS patient numbers

What experience do you have with pediatric patients with CBS?

I have not met any pediatric patients with CBS so far, but I don't think that up until recently I had been asking or warning parents about visual hallucinations. In addition, it is important to consider the age of the child, as they may have a pretend play friend/pet, or have poor or distorted vision, so they describe odd imagery based on their condition and level of sight. Many of the children I see have genetic eye diseases and over 60 percent can have systemic features including developmental delay and learning difficulties. All these components can make it difficult to assess CBS in this cohort.

At what age is CBS typically detected/identified?

CBS typically affects older people, reflecting the mean age at which common underlying conditions, such as AMD, diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma, cause loss of vision. The reported prevalence ranges in adults are 0.4-30 percent, but no formal epidemiological studies exist.

However, we know that CBS can occur at any age. We have focused on the elderly and the distressing situation where they experience visual hallucinations but are unaware of CBS, and hence fear that they are mentally ill or suffering from dementia. But the impact of such visual hallucinations for a child can be equally psychologically damaging, resulting in fear, mental health and behavioral issues. Overall, we need to raise awareness of CBS in children and adults amongst ophthalmologists, GPs, and all those working in the sight loss sector with patient contact.

Is any data on CBS being gathered now? What could it be used for?

My research team is in the process of commencing the first prospective epidemiology study across the UK for CBS in children, funded by the Thomas Pocklington Trust. I hope that as a result of this work, ophthalmologists will see the condition on the card, and it will trigger them to start asking patients about it – inadvertently raising awareness.

In 2018, the Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB) reported that 25,000 children aged between 0–16 years were registered severely sight or sight impaired in the UK. If we establish the incidence, sight loss conditions associated with CBS and the level of vision, this will help both ophthalmologists and pediatricians change practice by informing families about CBS, and how to cope with these visual hallucinations. For extreme cases, we will be able to offer the correct management, such as referring to child psychiatry.

How do you think this type of data could be collected in a coordinated manner?

In the UK we have the British Ophthalmological Surveillance Unit (BOSU) based at our Royal College of Ophthalmologists, which provides an active surveillance system involving all UK consultant ophthalmologists via a monthly reporting card scheme. They collect incidence data on rare diseases. Ophthalmologists will indicate that they have seen a new case of CBS, BOSU will notify the research team, and they will collect patient details through a questionnaire.

What preconceptions exist for CBS among ophthalmologists?

Some preconceptions are that it only affects adults and it is temporary – so, after complete sight loss, it stops. But we now know there are cases where it lingers, and I have heard from adults who experienced visual hallucinations as a child, and it really affected them psychologically. They never told their parents at the time or spoke of it due to fear; they found it hard to delineate from reality and imagery.

Do you think perceptions have changed, and are they likely to change in the coming years?

Judith Potts’ Esme’s Umbrella campaign has succeeded in raising awareness amongst health care professionals and patients alike. CBS is definitely talked about more; I know of several visually impaired community groups that have discussed this topic over coffee and unearthed how common this condition is, providing a sense of comfort to those affected. Raising awareness is great; the next job is to determine how prevalent this syndrome is and how we can tackle the severe cases, and manage patients appropriately.

Everyone whose sight is diminishing – no matter what age – must be warned that CBS might develop.

I asked Kirsty James – now the Campaigns Officer for the RNIB in Wales – what happened to her. She says, “When I was 13, I was told I would go completely blind from Stargardt’s Disease. I was so frightened, especially as we were not told anything about the condition and had to look it up for ourselves.” CBS was never mentioned and it was when she was living on her own, after university, that the condition kicked in. “There would be cars outside the flat on a cobbled street much too narrow for any traffic; I saw steps down that weren’t there or the gravel would suddenly appear to be a river in full flow,” she says. “Once, I looked down and saw blood all over the floor. I thought my guide dog’s paws were bleeding.” She told no one about her “strange visions,” and feared she was “going mad.” It was only when she met a low-vision specialist who asked her if she had heard of CBS, that she learned what was happening to her. She told me: “I just cried and said, ‘So I’m not going mad?’ I remember feeling a huge relief that I didn’t have a mental health problem: it was an eye condition.”

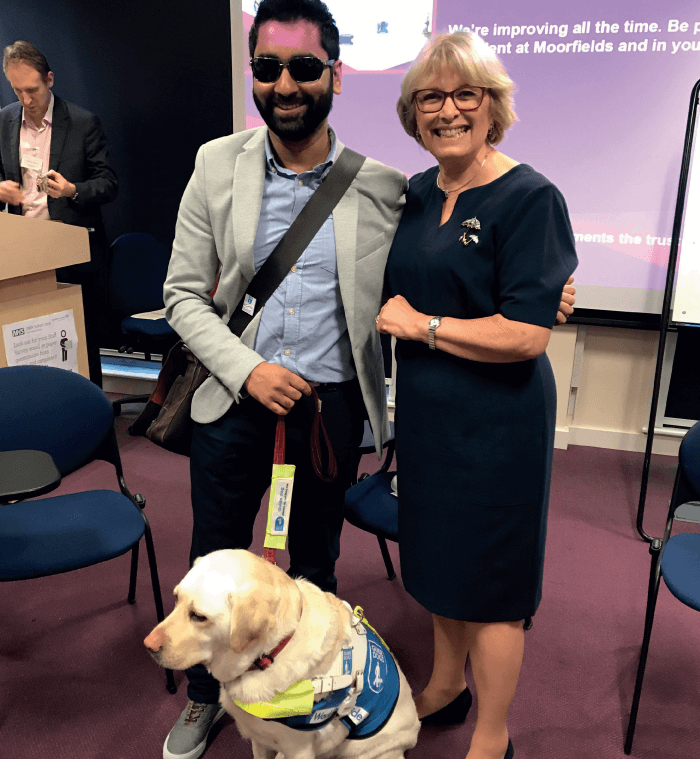

CBS Awareness Day last year was celebrated at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London. The hospital gave me a lecture theater in its Academy, and it was there I hosted the world’s first CBS Patient Day at which the CBS community were joined by ophthalmologists, doctors, researchers, ECLOs, ROVIs, medical students, and representatives from the eye charities.

One of the speakers was Amit Patel, who was a trauma doctor before a hemorrhage in both his eyes robbed him of sight. Not only has he had to come to terms with his new reality, but he has developed CBS. His hallucination is particularly terrifying. It is of a young woman, covered in blood, mud and tears. Amit says, “She stands in terrifying silence and she follows me everywhere – on the train, on the tube, in the street. My wife has even heard me shouting at her in my sleep.” Amit’s guide dog, Kika, has begun to sense before the hallucination occurs. She warns Amit by placing her head on his lap and remaining there until the hallucination vanishes.

This intrigued me, and I approached Claire Guest, the CEO of the Medical Detection Dogs’ charity. These amazing canines had featured in my Telegraph Column very often. Not only are they able to correctly detect cancer through their extraordinary sense of smell, but they are also able to alert their owners when medication – for conditions like Addison’s disease, epilepsy or diabetes – is required. I asked Guest if she thought it was possible that Kika could do this. Her answer was a very firm “yes” and then another “yes” to my next question: would she do some research to establish the change in Amit’s body that Kika is detecting? If we could feed that information into the research in Newcastle (see Researching CBS box), who knows what we might find?

For those who might not have heard of the charity, I asked Guest to explain the two sides of Medical Detection Dogs’ work. She began by describing the current disease-detection work: “Medical Detection Dogs (MDD) is a world-leading charity training dogs, pioneering both medical assistance and disease detection. The work is committed to carrying out empirical research to improve operations and to inform future medical technologies. To further this aim, MDD is currently working on a range of NHS approved clinical trials, exploring dogs’ ability to locate urological cancers, and is also researching the volatile detection of the malaria parasite and Parkinson’s disease.”

For CBS, it would be the medical assistance detection that would be needed, and Guest went on to explain how that would fit the CBS research. She said: “The other arm of MDD, Medical Alert Assistance Dogs, uses olfactory alerting ability for day-to-day support for people living with chronic conditions. The Assistance Dog is trained to alert its carefully-matched human partner to an oncoming emergency episode by detecting a change in his or her odor as their health condition changes; for example, a complex type 1 diabetes attack. There is anecdotal evidence that dogs may be aware of an oncoming visual hallucination in individuals with CBS, and so they could potentially be trained to alert and give a warning. MDD wishes to explore this further, train and partner the first dog, and collect data in relation to the reliability and impact of this canine intervention.”

Researching CBS

Kat da Silva Morgan, PhD Researcher at the Institute of Neuroscience, Newcastle University, UK

At Newcastle University, we are investigating how the activity levels of the visual part of the brain are different in people who experience CBS and hallucinations, compared with people with eye disease who do not. Based on the deafferentation hypothesis, which suggests that loss of sensory information from the eyes may result in compensatory hyperexcitability and disinhibition of the visual cortex, the study aims to investigate changes in the visual cortex by examining markers of cortical activity, such as blood flow and neurotransmitter concentrations. Using this information may allow researchers to further interrogate the mechanisms that precipitate into the occurrence of visual hallucinations in CBS.

Building on this work, researchers at Newcastle University are investigating a novel therapy for patients experiencing CBS, which uses non-invasive brain stimulation as a treatment for hallucinations in an ongoing placebo-controlled crossover trial informed by a pilot study conducted in collaboration with King’s College London. The trial aims to assess the therapeutic benefits of inhibitory non-invasive electrical brain stimulation applied over consecutive days to target specific areas of visual cortical hyperactivity in CBS, and its subsequent effects on visual hallucinations. Using both patient reports of changes to the subjective nature of their visual hallucinations and neurophysiological observations of changes to brain activity, the findings of this study will help inform further, larger scale, treatment studies in CBS.

Research delving into CBS only began in the 1990s when Dominic ffytche showed the first interest in the condition (along with other causes of visual hallucinations) since Charles Bonnet documented his grandfather’s hallucinations in 1760. With funding from the Thomas Pocklington Trust, Fight for Sight (which holds my Restricted Fund) and the National Eye Research Centre, Esme’s Umbrella has a research team at Newcastle University, working with ffytche. This research project is nearing its end and the results will be known in the spring of 2020. Shockingly, these are the only two centers hosting CBS medical research in the world. Even in the USA, which has the deep pockets of its medical foundations and universities, there is still no CBS research. My invitation to the ophthalmology department at Stanford University in California, to be the USA’s lead in CBS research, was declined. However, Fight for Sight has put out a call for another researcher. Funded by the money I have managed to raise and matched by Blind Veterans, CBS research will continue next year. We do not know, yet, where it will be or what specific aspect of CBS will be researched, but it is good to know that someone will be taking another step towards treatment and a cure.

Listening to the clinical psychologist who represents Esme’s Umbrella in the USA – Gary Cusick – it is evident that exactly the same scenario is playing out on the other side of the Atlantic. Gary Cusick works exclusively with the visually impaired (not a role we have in the UK, but one which would be welcome) at the McDowell Centre in Louisville, Kentucky – a comprehensive state rehabilitation center for people with every type of blindness or visual impairment. He says, “Clients typically do not talk about what they are seeing, perhaps for fear of being thought psychotic. I have been working with Esme’s Umbrella for the last year, answering questions regarding CBS from family members, clients and vision professionals in North America. CBS is still relatively unknown and may be mistaken for hallucinations seen in dementia patients. As the baby boom generation of the USA reaches the age when macular degeneration develops, it is vital that CBS be understood.”

Not only do we need Gary Cusick’s role to be replicated in the UK, but we also need specialist CBS nurses. Modeled on the way Macmillan nurses care for people who receive a cancer diagnosis, CBS nurses would do the same – liaising with ECLOs, ROVIs, GPs, sensory services, optometrists and ophthalmologists too, for the benefit of everyone in the family. Not being a charity, Esme’s Umbrella is not in a position to fund these nurses but, potentially, one of the large charities could step in.

David Probert, Chief Executive of Moorfields, comments, “CBS can have a significant psychological impact on patients who are also having to deal with the impact of losing a vital sense. The condition is poorly understood across the healthcare world and there is no clear treatment nor support service that is universally available to support people with CBS. It is important to support efforts to improve the care available for these patients, and Moorfields is proud to support this initiative.”

TH&IS commissioned the first CBS information video, which is available on the website, and is working now to make Dominic ffyche’s training course for nurses and anyone interested in qualifying as CBS carers interactive online; the course will carry CPD points.

Obtaining a referral to ffytche’s specialist national service for CBS has never been easy – mostly because the need to clone him is paramount – but now there are two new requirements in the Individual Funding Request process. The first is proof of exceptionality or rarity and the second asks for evidence of clinical effectiveness and previous treatment. As CBS is neither exceptional nor rare, and as there has been no research and no medication available, CBS patients fall at the first two fences. It is clear that the IFR is not fit for CBS purpose.

What would work? To have CBS included as part of specialist ophthalmologist services, so patients can access ffytche – and other doctors, yet to be appointed – through NHS commissioning. The complexities of achieving this are manifold and almost unintelligible to someone not familiar with the specialized terminology of NHS England.

Studies and research on treatment options are few. Michel Michaelides explains, “There are no studies of how CBS is managed by ophthalmology services in the UK. Clinical impression is that most ophthalmologists will explain the symptoms, reassure and signpost for further support. If CBS is clinically significant, it might be referred to a neurologist/neuro-ophthalmologist rather than be treated in a general ophthalmology clinic. There is no high-quality clinical trial evidence for the treatment of CBS.”

The words “clinical impression” and “might” illustrate the problem.

A few steps to create the much-needed medical and support pathway would save the healthcare system and social services millions. Giving evidence to the Minister for Loneliness, I explained how people living with severe CBS can find it impossible to distinguish between what is real and what is not. Eventually, they are too distressed and frightened to leave their homes – where they will require the input of social services. Others, who can no longer tolerate the terrifying or sexually explicit images, contemplate suicide. At the moment, if I speak to someone in this distressed state, I have to rely on the local low-vision charity to send an outreach worker on a visit, or suggest a phone call to the Samaritans. CBS needs to be included in The Campaign to end Loneliness.

Meanwhile, I am extremely grateful for all the help and support I receive from the ophthalmic sector as a whole – clinicians, nurses, ELCOs, ROVIs, and the charities. Insisting, quite rightly, that CBS needed a wider audience, Sandra Ackroyd and Tracy Atkinson from Sight Support Hull and East Yorkshire hosted an Information Day at York College in April of this year for me, and another is planned for Charles Bonnet’s 300th birthday on March 13, 2020.

As readers will be well aware, media coverage of sight loss issues is low down on the health journalists’ priority list. And yet, this is the sense that most people least want to lose. Unless there is a surgical breakthrough that restores sight, very little is written about the effect of a sightless world on everyday life. There is confusion, too, in the public’s mind between eye disease and conditions for which people wear glasses.

When I was a young actress, I appeared in an American play called Butterflies are Free, which is about a blind musician. I played his girlfriend and remember well the rehearsal days. The director insisted that the whole cast wore blindfolds all day, during lunch and coffee breaks too, so that we all gained some understanding of living in a sight-skewed or dark world. I will never forget the fear and helplessness that instantly took over – and that was only for a short time. When CBS appears, the loneliness and isolation already being experienced, is compounded by anxiety and depression, which often follow as quality of life takes a further downturn.

However, there is now considerable light at the end of the tunnel – not least from Rupert Bourne, Consultant Ophthalmic Surgeon at Cambridge University Hospitals, and Professor of Ophthalmology at Anglia Ruskin University, who encapsulates everything I am trying to achieve. He understands entirely the need for patients to receive a warning and for specialist nurses. Discussing CBS with me, he says, “One of the key features of CBS is that patients are fully or partially aware of their complex visual hallucinations that occur in the presence of vision loss. Given that the proportion of those with vision impairment who do experience CBS may range from 5 to 27 percent, it is beholden on clinicians, nurses and AHPs, like optometrists, to enquire about these symptoms, as it is quite possible that the prevalence may actually be much higher because of the stigmatization and fear of confiding, or of being considered mentally ill by relatives or health professionals. Correctly diagnosing CBS provides reassurance to the patient, but also means that the needs of the patient can be better assessed and managed. My clinical specialization is glaucoma, and when one asks about CBS symptoms in patients with glaucoma and vision impairment, I am always surprised how many patients do affirm these hallucinations and how often this has not been recognized by either the patient, the carer, or the clinical team. I think that enquiry about CBS symptoms should be a routine part of the history-taking by members of the clinical team and, often, this is best done by a nurse with awareness of CBS in advance of seeing the doctor or optometrist. Given that CBS may evolve during a patient’s clinical follow-up, it is important to continue making enquiries at subsequent visits rather than presume symptoms will not appear after the first visit, when often the history-taking is most comprehensive.”

CBS remained with my mother, Esme, for the rest of her life. Her confidence disappeared, as did her joie de vivre. She became exhausted with the constant need to “shunt her brain into another gear” to remove the hallucination – and then only temporarily. Waving her arms, sweeping the gargoyle off the table or clapping her hands took over her days. This was 10 years ago, but little has changed for the CBS community.

In 2020, no one should be left to cope alone when their life has been dramatically and negatively altered by what Charles Bonnet himself described as “the theater of the mind.”

References

- City of London University, “Caring for the Caregivers: Exploring support for caregivers of visually impaired people”. Available at: https://bit.ly/2O5Nb7G. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- City of London University, “Exploring support for family members and friends of people with visual impairment” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2DckRtO. Accessed November 22, 2019.