At a Glance

- There are no strict guidelines for dealing with DME patients who don’t respond to anti-VEGF injections

- Available options include continuing with the same treatment, switching to another anti-VEGF agent, or switching to a dexamethasone implant

- A recent real-world study shows better outcomes in patients who switched to a dexamethasone implant, compared with patients who were given further anti-VEGF injections.

We have a problem in DME management: the patient who simply does not respond to intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. There are no strict guidelines on managing such individuals – which is another way of saying we don’t always know what to do with them. But the problem isn’t going to go away. We need to develop a strategy to deal with it.

At present, options to manage anti-VEGF non-responders mainly comprise of the following:

- continue anti-VEGF treatment, using the same drug to which the patient is thus far unresponsive

- continue anti-VEGF treatment, but with a different drug

- switch to a dexamethasone implant.

What evidence is there to support each of these three routes?

Option 1: Continue unchanged

Evidence pertinent to this option includes data from the Protocol I and Protocol T randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Protocol I indicated that where anti-VEGF therapy has had little effect after three months, maintaining that same therapy for a year or more can provide a small visual gain – 2.8 letters, on average, after 52 weeks. Similarly, protocol T showed that patients deemed unresponsive at three months might expect a visual acuity gain of four to five letters after one year of continued treatment with the same drug. Note, however, that both Protocol I and Protocol T involved intensive treatment schedules – 8-10 injections over the first year. The question is, if we can only achieve a slight visual acuity gain in an intensive-treatment, controlled trial setting, what can we achieve in a real-world environment?

Actually, we don’t need to guess the answer to this question – we have the data. A retrospective analysis of 170 eyes (1) recorded that 38.2 percent were classified as non-responders at month 3; of these, about 50 percent converted to late responders after continued treatment. The key point is that only 50 percent of month 3 non-responders went on to achieve the modest visual acuity gains seen in RCTs.

Thus, as is so often the case, clinical trial data is not exactly reproduced in real life. Reason for this are strict inclusion criteria of RCT, which only apply for a part of our patients seen in daily practice, a strict follow-up of patients and a rather higher number of injections in RCTs.

Option 2: switch to another anti-VEGF agent

Might those who respond poorly to one anti-VEGF therapy be better served by a different anti-VEGF drug? At present, unfortunately, we have no RCT data that can answer this question. And real-world data tend to have drawbacks: many such studies report outcomes in patients that switched to another anti-VEGF drug, but do not compare these to controls (patients that remained on the same drug). Similarly, it can be difficult to apply rigorous inclusion criteria in real-world settings. Most of the studies on switching from one to another anti-VEGF agent in DME non-responders include patients with a long history of pre-treatment before switching. Thus, most studies are by no means limited to early non-responders who get switched at month 3. To my mind, due to these highly variable inclusion criteria – and the lack of a control group –the data from such studies does not allow to draw conclusions on the effect of switching among anti-VEGF agents. The fact is that we actually don't know so far if switching from one anti-VEGF agent to another is of benefit for early non-responders.

Option 3: Switch to a dexamethasone implant

Finally, if patients are not responding to anti-VEGF therapy, might it be better to switch them from anti-VEGF to a drug with a different mechanism of action? We explored this question very recently (2) (see box below).

Shall we stay, or shall we switch?

- Twelve-month study, real-world setting

- Retrospective case-control study; 14 study sites

- Comparing continued anti-VEGF therapy vs. early switch to dexamethasone implant in non-responders

- Inclusion: Previously treatment-naive DME patients deemed sub-optimally responsive after three anti-VEGF injections

- “sub-optimal response” = VA gain of 5 letters or less, or CST reduction of less than 20 percent

- n=110; mean age= 61.4 +/- 11.2 years; best corrected visual acuity (BCVA)= 20/60 Snellen

- Treatment group: switch to dexamethasone implant (n=38) after anti-VEGF loading phase

- Control group: continue with anti-VEGF for 12 months (n=72)

- matched control group (n=38)

- Outcome measures: change in BCVA, change in central subfield thickness (CST)

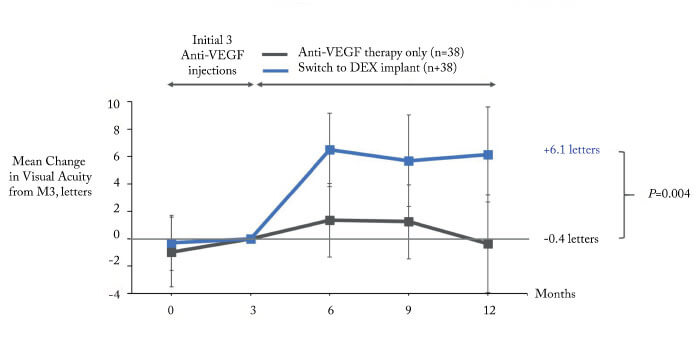

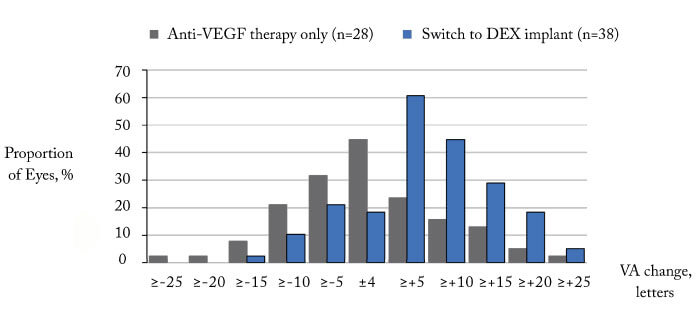

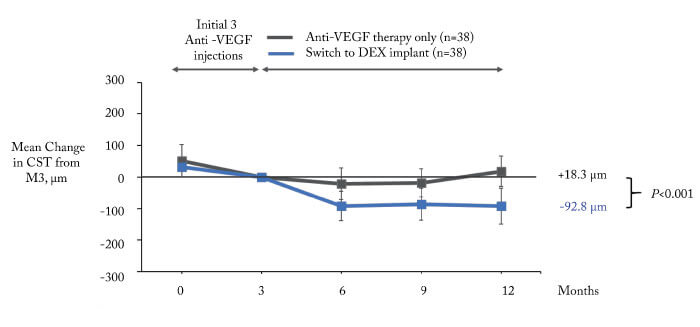

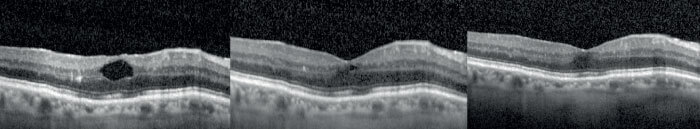

The results? The dexamethasone group had significantly better outcomes, both with regard to BCVA (Figure 1, 2) and CST (Figure 3). Furthermore, the patients maintained on anti-VEGF did not benefit from this continued therapy: there was no mean visual acuity or CST improvement after one year. Could it be that the observed lack of treatment benefit in the anti-VEGF maintenance group is due to under-treatment? After all, this is a common problem in real-world studies. However in our study we did not observe a better outcome in patients with more intensive treatment: stratifying the anti-VEGF maintenance group into two categories – 4-6 injections (n=35) and 7-12 injections (n=37) – shows that there is no significant difference between these categories in terms of mean visual acuity change (2). To conclude, the most likely interpretation of our data is that, on average, there is no benefit in maintaining anti-VEGF therapy in non-responders in real life; by contrast, switching to dexamethasone is likely to result in functional and anatomical improvements within a year.

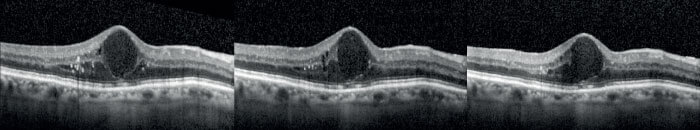

Finally, to give a concrete example of the benefits of switching to dexamethasone implants, consider the case of an 82-year-old gentleman, a patient at my clinic, in whom three ranibizumab injections had absolutely no effect (see box below).

When DME Gets Stubborn

- Male, 82 years

- Diabetes mellitus (15 years); HbA1c: 6.8 percent

- Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- Treatment-naive DME: started on ranibizumab injections

- Three injections: nil effect!

- Patient started to become demotivated for further treatment after 3 months since he experienced no benefit

- By contrast, the impact of implanted dexamethasone was evident within three months, and grew in extent over the 12-month follow-up.

Time to switch tactics

Of the three options available to those of us faced with patients who respond sub-optimally to anti-VEGF, it is clear that:

- Maintaining anti-VEGF therapy provides no functional or anatomical benefit, on average, in real-world conditions

- Switching to a different anti-VEGF agent has no reliable, supportive data at present

- Switching to dexamethasone implants provides significant benefits, in terms of mean changes to BCVA and CST, in a real-world setting.

From the data we have so far, I believe that on average dexamethasone implants provide the best option for patients who respond sub-optimally to anti-VEGF. This strategy significantly increases the probability of improved outcomes in a real-world setting. However, we urgently need more data on the characteristics of patients that benefit from one or the other treatment option in order to make individualized treatment decisions in those patients.

References

- E Maggio et al., “Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for diabetic macular edema in a real-world clinical setting”, Am J Ophthalmol, 195, 209 (2018). PMID:30098350. C Busch et al., “Shall we stay or shall we switch? Continued anti-VEGF therapy versus early switch to dexamethasone implant in refractory diabetic macular edema”, Acta Diabetol, 55, 789 (2018). PMID: 29730822.