How Good a Doctor Are You?

Your income may depend on it… but we have no real way to measure what actually matters to patients

Every physician strives to do their best for patients, but are we doing enough? Currently, there is no way to truly know how our outcomes compare with others, which also makes it impossible to know if we are “up to standard.” Implementation has begun on systems that measure individual physician outcomes and then base reimbursement upon them; such systems are a desirable replacement for fee-for-service because they could reduce unneeded care and improve the care that is delivered – but the devil is in the details…

Current methods do not truly assess our success as doctors. Detailed case-by-case oversight only occurs when there is an accusation of malpractice or negligence, and although devastating complications are sometimes reviewed at morbidity and mortality conferences, these do not measure routine care. Infrequent board exams might test a minimum standard of knowledge, but they cannot measure its application in daily practice. And although self-described Centers of Excellence may publish case series with success and complication rates, reports of general results in the wider community are rare.

The overall upshot? When selecting a surgeon for ourselves or a family member, it’s very difficult to objectively determine who is best – or even who is adequate. Online voting polls and magazines listing “Top” doctors receive much attention (mostly in advertisements for those voted highest), but are based on subjective responses from unknown respondents. One popular assumption is that a doctor who frequently performs a certain procedure or frequently treats a specific condition must be better than one who seldom does – and there is considerable evidence that this is correct. (1). However, the fact that surgery rates for a procedure vary dramatically by region of the country suggests that more surgery may not be better for patients (2). More research would be helpful to study the need for surgery and its quality, including its effect on patient quality of life (QoL).

There are many reasons why doctors and patients should favor standardized, publically available data on medical outcomes. For physicians, such data can improve the overall quality of care because it could help identify the methods that are most successful. For patients, it could provide reassurance that their medical team is competent.

The challenge is to develop outcome criteria that represent objective, quantifiable, and valid measures of the results of care. With the advent of electronic medical records (EMR) and national databases generated for billing purposes, some initial attempts have been made to do this. Unfortunately, the big databases that are available are not designed to assess outcomes, but rather to mimic paper charts and to record details for billing purposes. From them, one can determine how often tests, exams, or procedures were performed – but not whether they were appropriate, interpreted correctly, or had a reasonable outcome. The outcomes reported so far have been “process measures” – how many have you done? These data have been compared with Preferred Practice Patterns of national organizations, which are generated by consensus, but rarely validated by prospective studies. As big database studies can derive provocative findings – for example, the recent report that fewer elderly hospitalized patients die under the care of female internists than male internists (3) – prospective validation is vital for such work.

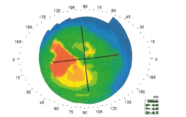

To use a specific example, consider how to assess the quality of care provided to a glaucoma patient. It is fashionable to propose that the best measure of outcome is the patient’s perspective, because patient-oriented outcomes are not routinely captured in clinical measures (acuity, visual field tests etc.). However, although QoL questionnaires theoretically measure the patient’s viewpoint, individual expectations and mental state can affect the correlation between clinical measures and reported QoL: the more depressed a person is, the worse they rate their visual function – even when it is normal. Furthermore, because diseases such as glaucoma have minimal disease-related symptomatology until late in their course, the inevitable side effects of standard eyedrop treatment – even when performed perfectly in accord with recommended practice – might lead patients to conclude (legitimately) that their quality of vision or life is either no better or even worse after treatment. How many of us can think forward 10 years to what would have occurred had such treatment not been given?

Currently, well-validated QoL questionnaires are not included in commercial EMRs. Medicare may have implemented post-visit questions for patients, but these deal in the “experience” during a visit (“how quickly were you seen?” or “did the staff treat you well?”). And though these may maximize service quality, they do not assess medical outcome. For instance, a 2012 Archives of Internal Medicine report demonstrated that respondents in the highest patient satisfaction quartile had a higher likelihood of hospital admission, greater expenditures, and higher mortality (4). And there may be other negative consequences – one possible contributing factor (among many) for the current opioid epidemic could be Joint Accreditation reviews that emphasized patient reports of inadequate pain relief (5).

Instead of QoL questionnaires, what standard clinical measures would be good benchmarks? Visual acuity after cataract surgery? Visual field progression rate for glaucoma? These exist in EMRs, but they may conflict with the patient’s view of their desired outcome. Patients who want uncorrected distance vision and need glasses after IOL implants are unhappy with uncorrected 20/20, just as few glaucoma patients appreciate that the dramatic slowing of field worsening with successful therapy is “better” than their natural course. To select a field criterion for glaucoma patients we need to know the rate of slowing that is compatible with best present outcome. It may not be “no” worsening, but an “acceptable” rate, adjusted by the distribution of case severity and patient demographics. If knowledge of physicians’ ranking is effective, it could produce a shift toward better overall outcomes, as in the cardiac surgery example mentioned above.

There has been a rush to produce outcome measures that are “practical” – data easily gleaned from the EMR. One such “quality measure” recently suggested was a particular IOP lowering after laser angle treatment for glaucoma… Compared with recently published data, the particular success criterion selected (from one 20-year-old clinical trial) is far too strict. Rather than picking immediate standards that later must be amended, studies are needed to estimate reasonable outcomes based on data from a variety of practice settings.

In my view, the healthcare system has never really stressed the things that are important to patients, and we need to develop methods to accurately benchmark if we are doing a good job for our patients. It is past the time when we can act as if someone else will make this transition meaningful – we all need to be productively involved.

The author reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

- HH Dasenbrock et al., “The impact of provider volume on the outcomes after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis”, Neurosurgery, 70, 1346–1353 (2012). PMID: 22610361.

- Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. “Variation in the care of surgical conditions: spinal stenosis”, (2014). Available at: bit.ly/DartAtlas. Accessed February 10, 2017.

- Y Tsugawa et al., “Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for Medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians”, JAMA Intern Med, 177, 206–213 (2017). PMID: 27992617.

- JJ Fenton et al., “The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures and mortality”, Arch Intern Med, 172, 405–411 (2012). PMID: 22331982.

- DM Phillips. “JCAHO pain management standards are unveiled. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations”, JAMA, 281, 428–429 (2000). PMID: 10904487.

Harry Quigley is A. Edward Maumenee Professor of Ophthalmology, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University.