Inspiring the Next Generation

Sitting Down With... Harry Quigley, A. Edward Maumenee Professor of Ophthalmology, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University

Why glaucoma?

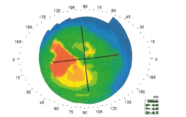

Among the ophthalmology specialties, I thought that glaucoma was the one with the most diversity. There was medical, surgical and laser treatment, various kinds of issues and problems, and lots of interesting diagnostic challenges. At the point in which I entered the field, the damage that glaucoma causes at the optic nerve was just starting to be understood as an important aspect of the disease, and I was able to train in Doug Anderson’s laboratory, which was applying new neuroscience techniques to the field.

From your research so far, what do you consider to be your most important finding(s)?

Helping to figure out not only how the retinal ganglion cell dies, but how to stop it from dying. Knowing the basic information about the pathways is important as it leads to a way in which we can stop it happening quite so often, and I think the fact that we have developed information about this is going to be the most important thing for glaucomatologists.

What are your thoughts on the future of glaucoma care?

I think sustained delivery will replace eye drops, so 10 years from now, nobody will be taking eye drops except for acute treatments such as a course of antibiotics. Right now, our most active area of research is trying to get a way of delivering neuroprotective agents to patients over an extended period, without eye drops or pills, so treatment won’t depend on whether an elderly patient with arthritis can squeeze a bottle and get a drop in their eye, or whether patients can remember to administer treatment. Another whole area of our research shows that in the real world, only half of the eye drops we prescribe are actually used, and many of those don’t effectively get onto the surface of the eye. So sustained delivery is the future without any question. I also think neuroprotection could eventually replace lowering eye pressure, but because we presently know that lowering eye pressure is protective, it is not ethical to perform the trial where you only do neuroprotection. It is best, and very feasible, to have sustained delivery methods that do both at the same time.

You’ve authored a book for people with glaucoma. Is enough being done to educate patients about their condition?

I think we could always do a lot more, and I think it would be worthwhile to study what patients think about how much they know, and how much more they would like to know. There is quite a diversity among patients; some don’t want to be confused with extra information and some want to know as much as possible, as it helps them feel in control of what is going on. We have a lot of evidence that patients who ask a lot of questions adhere to therapy better, and that almost certainly translates into better long-term preservation of vision. So that was one of the motivations for the book, and I wrote it as if I were talking to a patient, as they feel most comfortable reading about things that are scary and complex when it is understandable in a lay language. We sell the book in our office, and it is also freely accessible online – it is successful with patients.

You’ve been at the Wilmer Eye Institute since 1977 – any notable career highs?

The career highs are that we have grown big; when I joined there were seven of us on the entire faculty of ophthalmology, and I now have a division with nine glaucoma specialists. Along the years I have had the chance to interact with and train people who are leaders in the field nationally and internationally, and I take credit for them because, although they were already smart and motivated when they came here, we gave them opportunities to launch and get going. Much like your children or your grandchildren, those are the things that are most important. Not that somebody named a building after you or that you published 400 articles, but that somebody is continuing to write 400 articles – a multiplication of your effect. I think the high is that we have had a whole lot of people who have learned how to think and do, and how to take care of patients with glaucoma.

Who have been your mentors and role models?

I have a wonderful set of people I have been privileged to work with. In college I researched in George Wald’s lab; he later received his Nobel Prize for understanding the mechanisms of vision. At Harvard, John Dowling – who is widely seen as one of the most important vision researchers in our generation – let me do experiments literally in his office because there wasn’t room elsewhere. When I was a fellow at Bascom Palmer, it was in Doug Anderson’s lab that I began developing the animal models of glaucoma which now exist in monkeys, rats and mice. Irvin Pollack, who unfortunately died last year, was my residency glaucoma mentor, and he taught me a lot about how to be humane and caring for patients with glaucoma. And here at Hopkins, Edward Maumenee (whose chair I now hold) would give you lots of help, encouragement and ideas, and lead you to believe you were smarter than you thought you were. This was inherently really motivating because he was considered the dominant figure in both American and international ophthalmology. So I have just been blessed, and that’s just a few of the people who helped me out.

Day-to-day, what do you find most rewarding?

Right now I have enough experience in juggling a lot of things, so I am rarely bored! I balance the clinic and working with my five laboratory colleagues, and doing something in the clinical research realm that elucidates the mechanism of angle-closure glaucoma, or tells you how the optic nerve changes when you change the eye pressure, is just tremendous. We have some clinical research projects that are my latest, most fun ideas, and some of them crashed. And they should – if everything in research ends up with a successful publication then you are not challenging yourself enough.

We also have wonderful and generous patients who are donating money and making it possible for us to foster the development of young clinician-scientists, and we have a grant from the NIH to support these new careers. I am leading this, and I think it is probably one of the most fun things that I like to do. Lastly, now I have been here this long, I can introduce some of my junior colleagues to administrative duties…

What keeps you busy in your spare time?

I am involved in ecological restoration projects here in our local area. It all started three or four years ago when my wife won a prize for the best garden in Maryland, and we became interested in native plant gardening. I am part of a team that plants and takes care of trees in Baltimore city, and I am on the board of the city’s arboretum which has teaching programs for children about nature.