There is no doubt that the field of ophthalmology has advanced with the introduction of new surgical adjuncts. The proper use of these tools, however, requires successful practice and training to ensure that we are delivering the best care to our patients – especially when we are presented with complex cases. This reality applies not only to ophthalmology trainees, but also to experienced surgeons who may be implementing new surgical adjuncts in their clinical practice.

Surgical adjuncts in clinical practice

Surgical adjuncts may be used to address surgery in complex cases, such as small pupil size or intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS). Though surgeons may be able to plan for potential complexities, challenges may arise during the procedure that require surgical confidence with specific tools for a successful outcome. For instance, IFIS is commonly caused by the patient’s use of systemic alpha-blockers like tamsulosin (Flomax, Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Ridgefield, Connecticut, USA). Complication rates in these cases can remain low if the surgeon is aware of this medication history and can anticipate its influence by preparing to use appropriate tools, such as iris retractors, pupil expansion rings, or a viscoadaptive ophthalmic viscosurgical device (1). Tools like iris hooks and the Malyugin Ring (MicroSurgical Technology, Redmond, Washington, USA) have both demonstrated safety and efficacy in minimizing possible intraoperative complications that can arise during cataract surgery in eyes with small pupils (2). Cases of weakened or compromised zonules are also challenging, but can be managed with tools such as MST Capsule Retractors (MicroSurgical Technology).

Successful simulation training

Whether a surgeon is encountering a previously unfamiliar phacoemulsification machine or a new surgical adjunct, simulation training plays a critical role in reducing the rates of complications associated with cataract surgery and IOL insertion, most notably, posterior capsule rupture. What difference can well-designed simulation training make? A cataract surgery study from the Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ National Ophthalmology Database reported a 38 percent reduction in complication rates with the introduction of EyeSi simulator training for first- and second-year trainee surgeons (3). Low-cost, low-technology, smartphone-based simulator models intended for use by trainees at home have also been proposed to establish important skills like corneal incisions, capsulorhexis, and suturing. These may be especially important in regions without adequate access to more sophisticated simulators – like remote locations or developing countries – or in a pandemic (4). However, simulator training on the use of surgical adjuncts remains uneven. For instance, a recent survey of 67 ophthalmology trainees in Scotland found that only 3 percent had received formal simulation training in the use of capsular tension rings – a well-established surgical adjunct (5).

Though simulator training is critical for trainee surgeons, I always stress that established surgeons still require adequate training with less familiar techniques or adjuncts. Practice is important to develop the confidence needed during the procedure, especially if the need for tools like a surgical adjunct arises unexpectedly.

Procedures have become more nuanced with the introduction of these important tools – and the days of watching a brief video before attempting a new technique are over. In my experience, training videos do continue to play a role, but they should be used in conjunction with simulator training. I encourage surgeons without access to a wet or dry lab to practice in the operating theater on a model eye. Training sessions can be brief, especially if a trainer or experienced surgeon provides support and guidance.

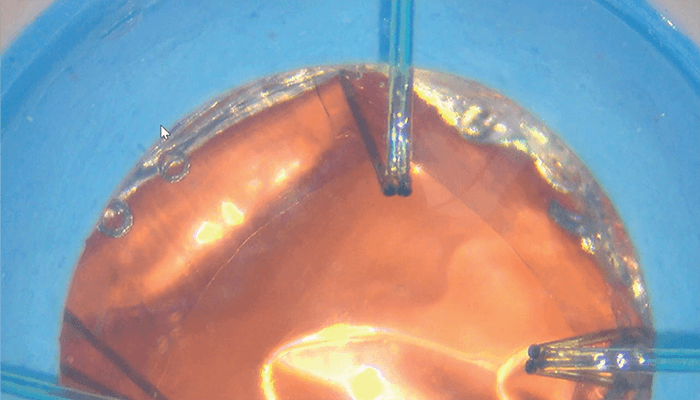

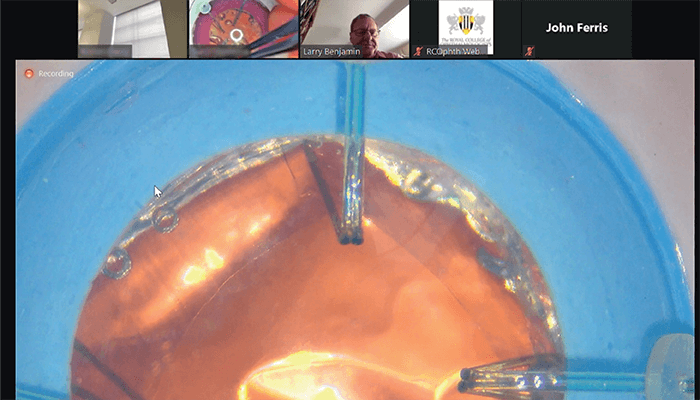

Figure 1. A trainee being supervised placing MST Capsule Retractors in an advanced cataract eye model (Phillips Studio, Bristol, UK).

Figure 1. A trainee being supervised placing MST Capsule Retractors in an advanced cataract eye model (Phillips Studio, Bristol, UK).

Figure 1. A trainee being supervised placing MST Capsule Retractors in an advanced cataract eye model (Phillips Studio, Bristol, UK).

Figure 1. A trainee being supervised placing MST Capsule Retractors in an advanced cataract eye model (Phillips Studio, Bristol, UK).

Training considerations beyond technique

The Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology (AUPO) has developed a framework for training that takes trainees through all aspects of patient care, from pre-surgical consultation and patient assessment through the procedure itself. Keeping this wider view of expertise in mind, one of the most important aspects of training and confidence is adequate communication – with both the patient and the support staff during the procedure. Good communication can help maintain a calm atmosphere that is especially critical if a procedure does not proceed as initially planned. Simulation is an important tool to prepare both the surgeon and staff for challenging cases, and simulators are designed to present difficult levels of complications. This aspect of training is important as it demonstrates that something done successfully in a straightforward case should also be managed in more complex settings, such as those when the patient is moving or agitated. Simulations train the surgeon and staff to maintain composure during a wide range of situations that inevitably arise during actual procedures.

The importance of surgeon self-assessment

After developing some degree of confidence with simulation training on new techniques or surgical adjuncts, trainees may wonder how to determine if they are ready to apply their new skills in practice. Fortunately, I have found that trainees are very good at scoring themselves, and validated tools are available for assessment. The Small Incision Cataract Surgery (SICS) Ophthalmic Simulated Surgical Competency Assessment Rubric (Sim-OSSCAR) is based on the International Council of Ophthalmology’s Ophthalmology Surgical Competency Assessment Rubric and has been considered a valid and reliable trainee assessment tool (6). A similar tool is in development that will help surgeons assess their level of skill with new techniques and specific surgical adjuncts.

Democratizing training

The use of remote training and trainee assessment tools, with adequate mentor support, offers a promising opportunity to democratize ophthalmology training worldwide. Trainees simply need a relatively affordable microscope, an internet connection, and a smartphone to access supervised expert training regardless of their physical location around the world. We know that simulation training works as evidenced by the reduction in complications following its introduction (3). With the possibility of accessible remote training options, we can now expand expertise with promising surgical adjuncts to a wider population of surgeons, which ultimately serves to improve patient outcomes – even in complex cases.

John Ferris is Consultant Ophthalmologist in the Gloucestershire Eye Unit, Royal College of Ophthalmologists Surgical Skills Faculty Lead, based in Gloucestershire, UK.

The author reports the following financial disclosures: Simulated Ocular Surgery and Simulation Gallery websites.

Hero image and teaser image Collage Elements Credit: Pixabay.com

References

- DF Chang et al., „Prospective multicenter evaluation of cataract surgery in patients taking tamsulosin (Flomax),” Ophthalmology, 114, 957 (2007). PMID: 17467530.

- P Nderitu, P Ursell, “Iris hooks versus a pupil expansion ring: Operating times, complications, and visual acuity outcomes in small pupil cases,” J Cataract Refract Surg, 45, 167 (2019). PMID: 30527439. [published erratum: J Cataract Refract Surg, 45, 257 (2019). PMID: 30704744.]

- JD Ferris et al., “Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ National Ophthalmology Database study of cataract surgery: report 6. The impact of EyeSi virtual reality training on complications rates of cataract surgery performed by first- and second-year trainees,” Br J Ophthalmol, 104, 324 (2020). PMID: 31142463.

- V Golash et al., “Low-tech intraocular ophthalmic microsurgery simulation: A low-cost model for home use,” Indian J Ophthalmol, 69, 2846 (2021). PMID: 34571647.

- C Mulholland, “Trainee experience with capsular tension rings in Scotland-the need for structured simulation exposure to surgical adjuncts,” Eye (Lond), 34, 1497 (2020). PMID: 32265512.

- WH Dean et al., “Ophthalmic Simulated Surgical Competency Assessment Rubric for manual small-incision cataract surgery,” J Cataract Refract Surg, 45, 1252 (2019). PMID: 31470940.

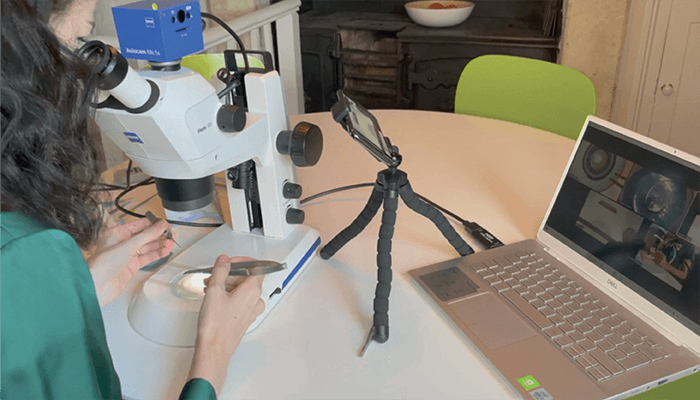

Figure 2. Microscope set up for remote teaching.

Figure 2. Microscope set up for remote teaching.