Establishing the actual prevalence of keratoconus is important for many reasons, not least because the allocation of public funds to healthcare activities, such as screening programs, is influenced by such data. And effective screening is essential if we are to diagnose patients sufficiently early to preserve vision with procedures such as corneal cross-linking (CXL). But what is the current situation regarding estimates of keratoconus prevalence?

From here

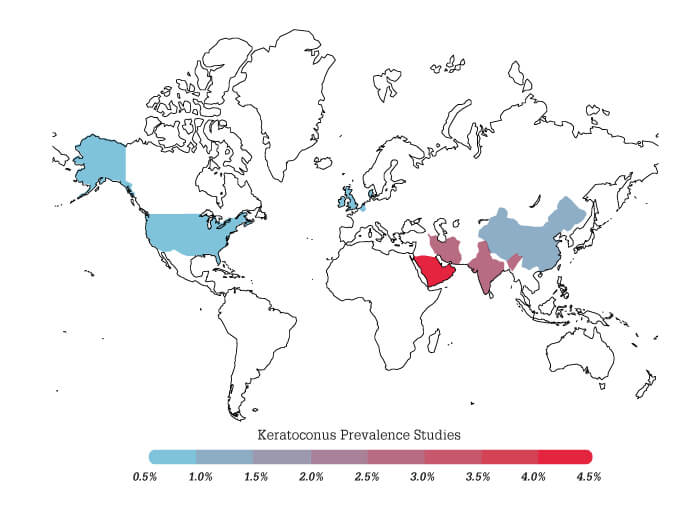

At present, it seems that keratoconus is generally thought to be a rare condition. This impression, however, is based on a 1986 paper by Kennedy and colleagues, which found a prevalence of 0.05 percent among Minnesota, USA, patients examined during the period 1935–1982 (1). Is it wise to rely on this research? After all, modern prevalence rates may have changed since then. Also, the methods used to identify keratoconus in that period (irregular light reflexes or irregular keratometry mires) are only likely to identify advanced disease. Accordingly, the study by Kennedy et al. may have missed many cases that modern corneal imaging instruments and techniques – such as Scheimpflug corneal tomography with the Oculus Pentacam – would find. Finally, it seems likely that keratoconus prevalence exhibits very significant geographic variation (Figure 1), and so the prevalence in a Minnesota population, therefore, may not reflect that typical of other ethnic groups.

To there

For all these reasons, we at the Light for Sight Foundation (www.lightforsight.org) decided it would be timely to assess the global prevalence of keratoconus. We began, however, with a pilot study – actually, it was part of an optometrist’s PhD thesis – in the Middle East, a region thought to have relatively high keratoconus rates. To avoid population bias, this study (see sidebar, “Keratoconus prevalence among pediatric patients in Riyadh”) we recruited people who presented to emergency rooms in general hospitals rather than specialist ophthalmological centers. These data have now been published (2), and it was gratifying to find that, of 1,044 eyes assessed that both Brad Randleman and Emilio examined and graded, there were only differences in opinion on keratoconus diagnosis. The key point, though, is that we recorded a keratoconus prevalence of 4.79 percent – almost 100 times more than that reported by the Kennedy et al. paper (1). It was clear to us that keratoconus, at least in some parts of the world, cannot really be described as a rare disease. This finding convinced us of the value of extending our pilot study to the global stage.

Keratoconus prevalence among pediatric patients in Riyadh

- Aim: To evaluate keratoconus prevalence among pediatric patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Design: Prospective, cross-sectional, observational, multicenter study

- Study population: Patients aged 6–21 years attending emergency rooms for non-ophthalmic appointments at four sites in Riyadh.

- Exclusions: Pre-existing ocular disease other than corneal ectasia or history of ocular surgery

- Methods: Bilateral corneal evaluation using a rotational Scheimpflug system (Pentacam HR, Oculus, Wetzlar, Germany), by a single expert individual, set at standard resolution, 25 images per scan.

Corneal images were rated by two independent experts; keratoconus was diagnosed based on a distinct focal abnormality of anterior corneal curvature with concomitant corneal thinning.

In cases where the experts differed regarding the diagnosis, a new unmasked evaluation was carried out by both individuals to achieve consensus. - Results: Evaluation of 522 patients (1044 eyes) suggested a prevalence range of ~4 to ~5.5 percent; this range resulted from inter-expert diagnosis discrepancy in 9 patients. Joint evaluation of these 9 cases achieved consensus, resulting in a final prevalence measure of 4.79 percent (2).

- Conclusions: In Riyadh, the prevalence of keratoconus is considerably higher than the values found in previous studies, and nearly 100-fold that reported for a North American population over the period 1935-1982 (1).

The excellent concordance between the diagnostic judgments of two independent examiners (discrepancies occurred in only ~1 percent of the study population) suggests a robust case-finding methodology, which gives additional credence to the ~5 percent prevalence estimate.

Direction of travel

Accordingly, we are now extending our investigation to many other countries worldwide. This expansion phase has benefited from constructive feedback from peer reviewers when we submitted the pilot study data for publication in the British Journal of Ophthalmology. We modified our study design based on these comments and developed an improved protocol. And that became the basis for K-MAP, our global study of keratoconus prevalence. A key aspect of K-MAP is its simplicity; to participate, a site need only meet five criteria; to have:

- ethical committee approval in place

- access to an Oculus Pentacam for diagnostic measurements

- an on-site anterior segment specialist to conduct measurements

- an appropriate system for obtaining and storing patient signed consent forms, and

- signed the publication policy relating to K-MAP data and study protocol.

Progress to date has been most encouraging; centers in South America and Russia have already confirmed their participation, and the Russians, in particular, are making a very significant contribution to K-MAP data. Other interested countries include the USA, Switzerland, Australia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Mexico, Peru, and Syria. Some of these are just at the point of joining up, while others are already collecting data.

We have been delighted to find that optometrists are particularly interested in supporting the K-MAP study; these professionals are often well-positioned to advise us on how best to access the patients, which can be a major obstacle. For example, an optometrist colleague in Australia, obtained funds to support vision screening in schools via a grant application co-submitted with local ophthalmologists; the keratoconus assessments were simply added on to the ophthalmologists’ other vision tests. Similarly, in South Africa, an optometrist will also conducting screenings within their public school system – which is our ideal scenario. And, in the pilot study, our PhD student in Riyadh – also an optometrist – opted for a different approach; she managed to set up an Oculus Pentacam in children’s hospital waiting rooms and proactively asked people if they would like to be examined.

What are the implications of data obtained to date? At the very least, our pilot study suggests that keratoconus prevalence among children and adolescents, at least in some parts of the world, is far higher than previously thought. If K-MAP generates similar findings, it will be difficult to continue to think of keratoconus as a “rare” disease, suggesting the need for increased screening of pediatric patients – ideally within the school system – to support early diagnosis and treatment before an irreversible loss of vision.

Why may the true prevalence rate be much higher than found in previous studies? One contributory factor could simply be that keratoconus prevalence is increasing in many parts of the world; certainly, my impression – and that of many of my fellow ophthalmologists – is that keratoconus is becoming increasingly common. This increase could be caused by several factors, including environmental changes – for example, drier weather and higher pollution – that lead to increased eye-rubbing. Finally, of course, genetic factors associated with particular populations might also contribute to a high prevalence in specific regions – perhaps this was the case in Riyadh.

The K-MAP destination

It no longer seems viable to rely on the lowest of all prevalence estimates – the Kennedy et al. study – as a guide to keratoconus prevalence. Our pilot study, generated with modern diagnostic technology, suggests that the true prevalence may be nearly 100-fold higher – at least, in some parts of the world. Our K-MAP study, being global in scope, is designed to uncover worldwide prevalence rates, and our current impression is that they will be closer to the 5 percent prevalence of the Riyadh study than the 0.05 percent prevalence of the Minnesota study. In any case, the K-MAP data will be invaluable in guiding decisions regarding pediatric screening programs and related healthcare strategies. Future studies will build on K-MAP to investigate prevalence in specific high-risk groups, such as adolescents with Down’s syndrome. The overall impact of these studies will be to refine our views on who to screen and when, and hopefully will direct beneficial changes to the keratoconus treatment paradigm.

References

- R Kennedy et al., “A 48-year clinical and epidemiological study of keratoconus”, Am J Ophthalmol, 101, 267 (1986). PMID: 3513592.

- E Torres-Netto et al., “Prevalence of keratoconus in paediatric patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia”, Br J Ophthalmol, 102, 1436 (2018). PMID: 29298777.