To read Ray Radford’s 2021 update on monovision, click here

- As cataract and refractive surgery improves, patients’ demands grow – “perfect” vision, with good near and distance focus, is now want many patients want

- Monofocal intraocular lenses are one way of achieving the best possible range of vision for patients without introducing unwelcome aberrations

- Though many surgeons doubt patients’ ability to adapt or be satisfied, monovision has been successful in the over 90 percent of patients

- The key to patient satisfaction with monovision is to listen to your patients, clarify their expectations, and establish reasonable and well-understood goals

Monovision is not a new concept. In fact, some people’s vision is naturally set up to provide them with both distance and near vision, helping them avoid presbyopia without a doctor’s help. So why is this vision solution so overlooked by cataract and refractive surgeons? At the 2013 meeting of the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons (ESCRS), there was only one main speaker to discuss monovision. During a UK talk, I asked an audience of consultant surgeons to raise their hands if they routinely discussed presbyopic correction – in particular using monovision techniques – with their UK National Health Service (NHS) patients. Out of about a hundred surgeons, fewer than five hands went up. It’s clear that monovision isn’t getting people’s attention. So why should we offer it to our patients?

Most patients in NHS practices are between sixty and ninety years of age. They’re all presbyopic by default, In the NHS, a monofocal lens is the “standard premium” lens. Monofocal lenses have been developed over the last 50 years, so at this point they are extremely well manufactured of high quality and very reliable. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists considers it best practice to offer patients a choice of focus – we know that patients who are myopic may wish to remain myopic because that’s what they’ve been used to all their life, whereas those who suffer from hyperopia have had the disadvantage of losing their near vision much earlier and have always been spectacle-dependent, so it’s nice to offer patients the option of seeing in the way they’re most comfortable seeing or giving them something new.

Demanding patients

As the accuracy and recovery of cataract surgeries continue to improve, patients now expect – and demand – better outcomes, not just in terms of the surgical success itself but in terms of refractive results. I recently had a patient worried that her vision wasn’t perfect within 24 hours because her neighbor, who had undergone the same cataract surgery days before, could see perfectly well by then. Such is the rapid recovery of most elderly patients from NHS cataract surgery. Given that our patients are more demanding as a result of our own improvements, it seems only sensible to have a discussion with them about their refractive outcome expectations. Many will tell you they want the best possible distance vision – but they’re disproportionately surprised and dismayed to find they don’t have equally good near vision after successful surgery as they have not really listened to or understood the preoperative consent. People hear often only want they want to, readily listening to the positive message about how great modern cataract surgery is, assuming wrongly this is for all distances and tasks. Some consultants even run practices dedicated to implanting secondary lenses or offering other procedures to patients whose ametropia has been well treated, but who didn’t fully understood before surgery that they would lose their near vision as a result. So to me, it makes sense to offer people the option of retaining some near vision in one eye before going ahead with cataract surgery and making sure they understand want is meant by near and distance vision by physically demonstrating with charts and reading font books.Avoiding “Vaseline Vision”

Monofocal lenses have some specific advantages over multifocal intraocular lenses (mIOLs), and key among them is the much higher mIOL exchange rate. Nearly all patients will suffer from glare or dysphotopsia of some type when using mIOLs. There’s also often an overall reduction in contrast and many of patients will complain of “Vaseline vision,” a common term for complaints of filmy, waxy or hazy vision after implantation (1). So widespread is the knowledge of that problem that some experts in the field recommend early surgery on the second eye, so that patients can’t compare one against the other. The one thing no multifocal surgeon would recommend is the implantation of a monofocal in one eye and a multifocal in the other – that isn’t considered best practice. But mIOLs are not the only way. For some people, monovision is a natural state. Others have already tried it using contact lenses. It isn’t new to the surgical scene, either; if you type the term into an Internet search, you’ll find a plethora of advertisements recommending monovision created by LASIK. Clearly, then, we’re very used to offering it to patients – and patients are ready to try it. So why don’t we include it in conversations about NHS cataract surgery, too?Satisfaction

For many years, the literature has papers from all over the world supporting monovision. Figures vary between publications, but satisfaction with intraocular lens monovision certainly reaches 90 percent (2,3), which agrees with my own experience. This outperforms most of the quoted figures for multifocal lenses (4–6), which isn’t surprising given that a monofocal lens doesn’t have all the disturbing visual symptoms of a mIOL (4). It’s worth noting that some recent publications discussing multifocal practice have suggested that, to give patients the best outcome and guarantee better near vision, surgeons should consider a mIOL with preferential near correction. It strikes me that, in simpler terms, this is just monovision – but with the potential disadvantages of mIOLs.Risking binocularity?

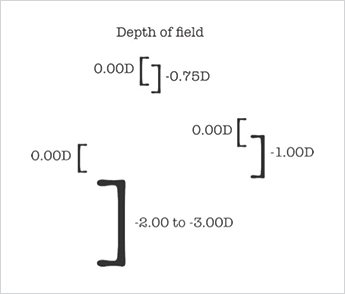

The major concern with monovision, of course, is the risk to binocularity. But I don’t often see discussion of the fact that patients with recent, genuine (1.5 to 2.0 D anisometropia) monovision actually maintain summation. The eyes, of course, don’t actually see anything; the brain interprets the images it receives. We’ve all had patients who, in a single eye, have attained 6/5 and N5 with a simple monofocal lens despite minor astigmatism – indicating that the visual system in certain individuals is capable of far more than we assume. We certainly don’t understand it fully. But, given the brain’s ability to interpret visual information so well and to maintain summation, then as long as we don’t give people an extreme degree of monovision, (>3D of anisometropia) the most likely result is a very happy patient. In those terms, monovision is actually a misnomer. Most patients will maintain binocularity, particularly if we don’t exceed a refractive aim of -1.5 D in either eye. I have my own set of guidelines for different types of patients. In hyperopes, for instance, I tend to go up to 0.75 D to give them some near vision. Most patients achieve around the N8 mark, which is about the size of newspaper print. For patients with a lower degree of hyperopia or low myopia, up to 1 D in the near eye usually gives them reading vision on the order of N6 – but if they want particularly good near vision, then an aim of 1.5 D usually achieves an N5 correction unaided. Patients who already have refractions of above 3 D, I leave with 2 D in their near eye, which usually results in N5 to N4.5 vision. I do occasionally aim for -3 D in extreme myopes, because they have already adapted to holding things close and prefer to maintain that status quo. I find it slightly annoying when people tell higher myopes holding things close, “You’re not looking at it properly,” when that’s perfectly acceptable given that’s the way their vision works. Why change that, when to do so would reduce their comfort and satisfaction?Understanding the patient’s needs – and delivering what you promise

There are similarities between counselling patients for monovision and for multifocals, because there’s no guarantee that they won’t use spectacles for some tasks. Some people are very detail-oriented and want a very specific focus at very specific points, so they still want three pairs of glasses for their daily activities. Not everyone needs that – most people get by with the depth of focus that blended vision provides. I also think it’s very reasonable to check dominance and, if the patient has a clear preference, correct that eye for distance. Consultants who offer monovision feel that it’s important to make sure distance correction is as good as possible, and I fully agree. Patients’ vision should be at or above driving standards – at least 6/9, and preferably 6/6, in the distance-corrected eye. To achieve this, we need good surgery and accurate biometry. To make refractive correction as accurate as possible, I suggest doing the near eye first. This allows fine-tuning of their distance eye and, having achieved some near vision, the patient is delighted to see distance once they’ve had the second eye done. In my experience, most people don’t want to lose all their near vision, either. The hyperopes I treat are amazed to be able to read anything at all, though I take care not to push their near correction too far. But neither of these is a hard-and-fast rules; patient preference should always be taken into consideration when making any surgical plan.Why does monovision work?

So why does monovision actually work? Despite a number of very senior surgeons in the UK who say it doesn’t, it certainly works for a majority of patients. It works because we retain some depth of field – and possibly because modern monofocal lenses are premium lenses and therefore have very few aberrations, resulting in better quality of vision. Patient preparation is key, too. It’s always interesting to ask patients, before offering refractive correction, what their expectations are, what they already know, and with whom they’ve discussed it. Some patients come already primed to ask for monovision based on success in people they know or having tried contact lens monovision prior with success. Others come in saying they don’t want it based on other information they’ve gathered from their opticians or from people who’ve tried contact lens monovision and been unhappy with it. In cases of doubt or strong preference against, I respect the patient’s wishes and avoid monovision. The issue with contact lenses monovision dissatisfaction, though, is potentially that the patient’s vision isn’t static. People taking their contact lenses in and out means the brain has to adapt to the new image each time the refraction changes, rather than adapting to a constant stimulus and or adapting and accepting the images being processed. I find it interesting that some multifocal practitioners tell their patients they need to wait up to six months to adapt to the new image. I’ve only had one patient take three months to adapt, and he had a high degree of monovision. The majority of patients seem to adapt within hours or days – a few weeks at the most. Through close liaison with occupational health doctors, I’ve provided monovision to many professionals for whom sight is vital, from police drivers to surgeons, and they have all found monovision to be not only convenient, but excellent. When I have asked should I use a multifocal in professionals with visually demanding occupations the answer has usually been to avoid doing so.Who might benefit?

Of course, it isn’t for everyone. Not all patients are happy with their degree of monovision. I had a myopic patient who wanted more myopia because that’s what they were used to, which is why I prefer a near aim of at least -1.5 to -2 D in myopes. There was another who had a fantastic result, 6/6 and N5 unaided, but wasn’t comfortable, so they had a secondary lens implanted to make both eyes distance-focused. I’ve even had a patient who had 6/6 and N5 vision unaided, but was dissatisfied with their middle distance vision and couldn’t improve it by using glasses – so again they sought secondary correction to have both eyes the with the same focus. But these represent only a handful of people out of many hundreds and, compared to some of the success rates in previous generations of multifocals, the overall results are very encouraging. There are, of course, cautions when giving people monovision, particularly in the presence of ophthalmic disease or at high degrees of astigmatism. Surgical incisions might help reduce corneal astigmatism, and it’s possible to reduce up to two diopters simply by providing opposite clear corneal incisions – although, for more marked astigmatism, a toric lens offers the best chance of success. Toric lens monovision works, I have experienced it.Explaining, listening and gaining mutual understanding

The most important aspect in providing monovision is to understand the patient’s needs and expectations, and to communicate clearly with your patients and colleagues to ensure that everyone understands what the aims are and what’s achievable. For surgeons who have not previously offered monovision on the NHS, it’s probably best to start cautious and offer 0.5 to 0.75 D to interested patients. That will give them at least some degree of near vision. Meanwhile, build your confidence by looking at world literature. There are plenty of recent papers from China and the USA, both of which have huge populations of patients receiving monovision. But the single most important concept to grasp is that communication is paramount. Explaining, listening and gaining mutual understanding is critical to achieving patient satisfaction. In practices where patients are heard and their expectations managed and met, I truly believe that “monovision” is, as I’ve said, a misnomer. Satisfied patients would agree with me that better names for the procedure might be “presbyopic corrected vision,” “spectacle-free vision,” or even the term that I feel really sums it up best – “clear vision.” Patients themselves often sum it up as simply “amazing” or “brilliant.”Ray Radford is a consultant ophthalmic and oculoplastic surgeon at multiple practices in the UK.

References

- FA Bucci Jr., “Vaseline vision dysphotopsia”. Available at: http://bit.ly/1HfZcPU. Accessed June 25, 2015. S Greenbaum, “Monovision pseudophakia”, J Cataract Refract Surg., 28, 1439–1443 (2002). PMID: 12160816. J Xiao, et al, “Pseudophakic monovision is an important surgical approach to being spectacle-free”, Indian J Ophthalmol., 59, 481–485 (2011). PMID: 22011494. F Zhang, et al, “Visual function and patient satisfaction: comparison between bilateral diffractive multifocal intraocular lenses and monovision pseudophakia”, J Cataract Refract Surg., 37, 446–453 (2011). PMID: 21333868. NE de Vries, et al., “Dissatisfaction after implantation of multifocal intraocular lenses”, J Cataract Refract Surg. 37, 859–865 (2011). PMID: 21397457. P. Sood, MA Woodward, “Patient acceptability of the Tecnis® multifocal intraocular lens”, Clin Ophthalmol. 2011; 5, 403–410 (2011). PMID: 21499564.