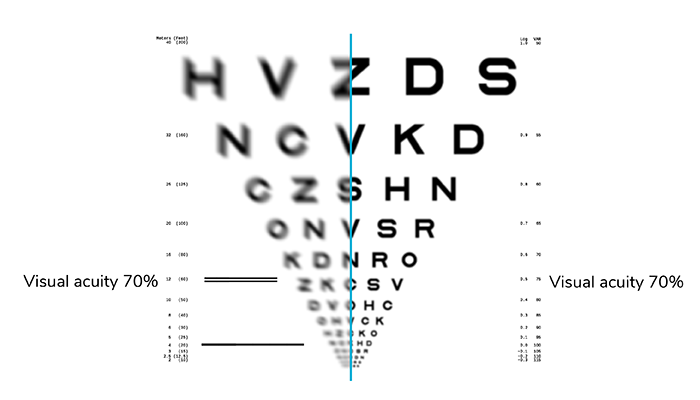

Figure 1. The difference between visual acuity and visual quality. In both images, the patient has the same visual acuity, but different visual qualities – and it is the degradation of the latter that causes so much of the visual disability in patients with corneal ectasias.

What is the current state of the art for rehabilitating the vision of patients with keratoconus? That’s one of the questions we are most frequently asked, and the answer is always, “It depends.” There is certainly a spectrum of options, but the best one depends on the individual patient’s cornea. Patients with complex corneal pathologies, such as failed refractive surgeries and highly advanced corneal ectasias, are often referred to our clinic – the ELZA Institute in Zurich, Switzerland – and we have decades of experience in managing such cases. Here, we share what we have learned over the years.

Quality versus acuity

With keratoconus, there can be a big difference between visual acuity – what a patient can read on a chart – and visual quality (see Figure 1). Early on in the development of a cone, patients not only develop increasing amounts of ametropia, but also regular and – crucially – irregular astigmatism, which causes the biggest problems.

Cone development creates irregular astigmatism because the distortion of the corneal shape increasingly creates irregular surfaces of the anterior and posterior cornea, and this manifests as the hallmark higher-order aberration (HOA) visual disturbances that keratoconus is famous for causing. Irregular astigmatism cannot be corrected by spectacles or regular contact lenses alone.

Surgical intervention

If a patient has a mild, stable keratoconus with satisfactory daytime vision with spectacles, the best course may be to take no action until the condition changes. If progression does occur, then corneal cross-linking (CXL) should be performed to halt further deterioration.

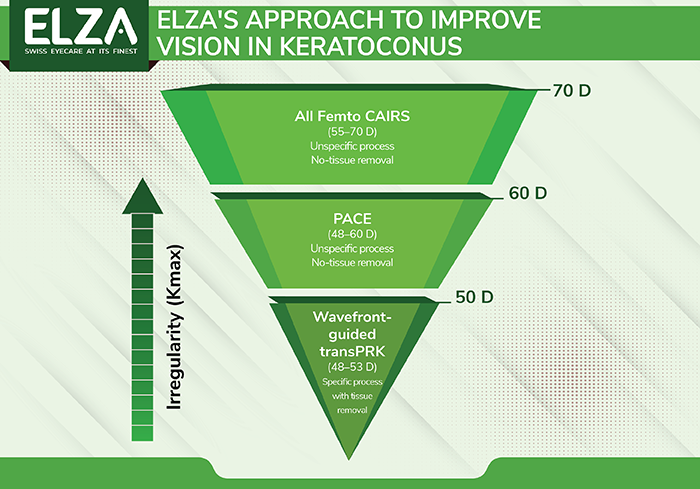

If surgery is necessary, there are several options available, and these can be used in isolation or in combination to rehabilitate vision as much as possible (see Figure 2). Typically, where we start on this journey depends on the amount of corneal irregularity present in the cornea. If there is a significant amount, we start with a less-specific process to help flatten the cone; if required, we follow this with more targeted approaches to further improve vision.

Ring segments

Intracorneal ring segments (ICRS) is the surgical intervention that typically delivers the greatest corneal regularization effect. ICRS, which have been available for over 20 years, are crescent-shaped devices made from polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA); they are implanted into crescent-shaped pockets made in the stroma (either by a blade or a femtosecond laser). Once implanted, the presence of the ring segments raises the cornea and causes the corneal curvature over the cone to flatten. This not only helps to redistribute biomechanical forces away from the cone region, but also to regularize the shape of the cornea, all without removing tissue. ICRS can also be removed at a later date; in other words, the procedure is reversible.

The corneal reshaping induced by the ICRS acts to reduce corneal irregularities and enhance patients’ quality of vision. The only disadvantage with ICRS is that, in some cases, the rigid nature of the ring can result in ring migration or extrusion – and there is a very small risk of corneal infection or neovascularization.

So, how can this be improved? By making the rings from corneal tissue…

CAIRS and All Femto CAIRS

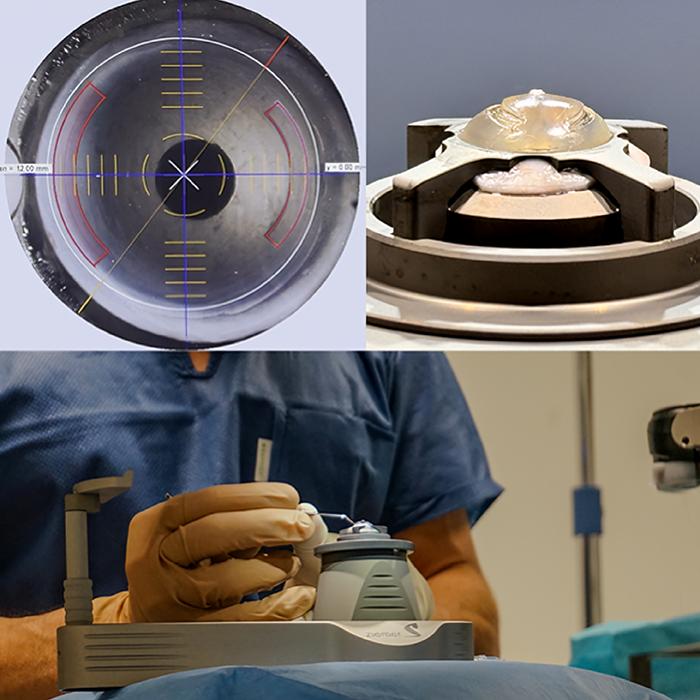

The brainchild of ophthalmologist Soosan Jacob, CAIRS – corneal [allogeneic] intrastromal ring segments – involves the creation of ring segments from human donor corneas. With CAIRs, the tissue inserted into the pocket (essentially collagen, rather than rigid PMMA) should have a lower risk of migration or extrusion. Cornea, cataract, and refractive surgeon Shady Awwad worked with Soosan to further enhance CAIRS to make it a fully femtosecond laser-based procedure, called All Femto CAIRS.

With ICRS, the most appropriate ring length is chosen from the manufacturer’s selection; it is then inserted into the appropriately placed pocket. With All Femto CAIRS, the surgeon can specify the exact dimensions of the corneal ring segment, as well as the placement of a femtosecond-laser created tunnel in the stroma (see Figure 3). This makes the procedure as customizable to each patient’s cornea as it possibly can be. Awwad observes that “the allogeneic nature of the rings means that we can place the rings in pockets that are shallower in the stroma, and this amplifies the reshaping effect, compared with PMMA rings placed in deeper pockets,” suggesting that CAIRS procedures have more potential to regularize corneal shape than ICRS. This year, the ELZA Institute became the first center in Switzerland to offer All Femto CAIRS. Our experience with it – and that of our patients – has been entirely positive to date.

Figure 2. The ELZA pathway for ectatic cornea rehabilitation surgery. There are several surgical options available today, and in isolation, or combination, can be used to improve the regularity of the cornea, and the visual quality too.

PACE

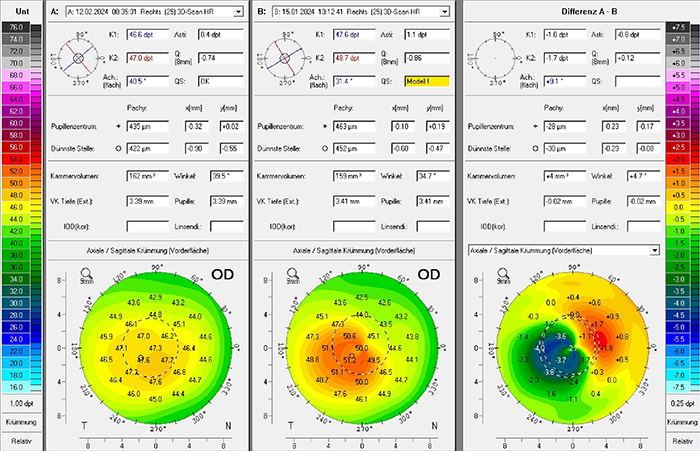

If a cornea requires cross-linking, an excellent option in many cases is PACE (PTK-assisted customized epi-on CXL), which we described in a recent issue of The Ophthalmologist. PACE is a second-generation customized CXL method that uses a phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) ablation to remove the corneal epithelium above the cone (but no stromal tissue), which is then followed by a short, high-fluence partial epi-on/epi-off cross-linking procedure. The cross-linking effect is greatest over the cone – also the region that requires strengthening – and less in more peripheral regions. This is because PACE produces a riboflavin gradient (greatest over the epi-off cone region, lower in regions where it is required to penetrate the remaining epithelium), as well as a UV gradient (epithelial cells absorb UV energy) and an oxygen gradient (epithelial cells consume oxygen, which is required to diffuse into the stroma and oxygen is rate-limiting for the UV-riboflavin photochemical reaction that strengthens the cornea). This results in a significant immediate flattening of the cone and regularization of the cornea (see Figure 4). Over six months to a year, the method leads to around 8–12 diopters of total flattening. If a further flattening effect is required on the cornea, PACE can be performed after All Femto CAIRS. In suitable corneas, either procedure (in isolation, or in combination) can be followed by therapeutic PRK surgery if necessary.

Figure 3. Creation of the All Femto-CAIRS ring segments from the donor cornea.

Wavefront-guided transPRK (surface ablation)

Once a cone is cross-linked, the cornea may flatten slightly – up to 1 diopter – over the next six months. For corneas with sufficient biomechanical strength and residual tissue after CXL, wavefront-guided photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) surface ablation with an excimer laser can be considered (see Figure 5). This technique, primarily aimed at corneal regularization rather than refractive correction, can significantly reduce HOAs. Our excimer laser platform, the SCHWIND Amaris, has a built-in wavefront-guided ablation algorithm that can specifically address and reduce the HOAs in irregular corneas. It is a precise process, suitable for corneas up to a general limit of 52 or 53 diopters, and can significantly enhance visual quality by addressing irregular astigmatism.

Figure 4. The effect of PACE on corneal topography; before and 5 minutes after the procedure.

Patient-centric care

As we have shown, there are several options available for rehabilitating the vision of people with keratoconus. But combining them can yield better results than using the techniques in isolation. The “best” approach? Well, that is specific to each and every eye, and selection should be driven by the topography, tomography, pachymetry, and biomechanics of the cornea, as well as, of course, the experience of the surgeon and the wishes of the patient.

Ultimately, whether the treatment is surgical or non-surgical (for example, special contact lenses), it’s important for patients to know that – no matter how bad their vision is with keratoconus – there is hope.

Figure 5. Wavefront-guided TransPRK being performed.