Few of us would claim that glaucoma management is ideal: we lack the tools to predict the course of disease in any individual, and we are frequently required to make clinical decisions under time-limited and stressful conditions. But the reality may be even worse than we thought: the truth is that most of the patients we label as “glaucoma suspects” will never suffer glaucoma-related vision problems. Yet we send them from our clinics burdened with the fear of encroaching blindness, and often recommend unpleasant therapies or traumatic surgery to manage a risk we cannot quantify.

Other than waiting for better predictive tools, is there anything we can do to change this state of affairs? I believe so. Firstly, we glaucoma specialists need to adopt a more patient-centric approach and take greater account of the patient’s own risk attitude and individual needs. And secondly, we need to reflect more deeply on the extent to which our decisions are affected by unconscious bias and limited knowledge. These actions are within the capability of every glaucoma physician, and would, I believe, result in better, more individualized patient care.

It’s telling to listen to the language commonly used in a glaucoma clinic: we happily inform patients they are “glaucoma suspects” without considering the effect we are having. Think about it from the patient’s perspective: when we say “glaucoma” – even when qualified by “suspect” – the patient most likely hears “blindness.” We all know that elevated IOP in the absence of disc changes or field loss is not equivalent to clinical glaucoma, but in our patients, we allow this observation to trigger the fear of sight loss. In consequence, our well-meant “glaucoma suspect” label reduces patients’ quality of life forever, particularly if they have any family history of blindness. Thus, our good intentions end up causing harm to people who do not actually have glaucoma when they first visit our clinic.

We should also be mindful of the time asymmetry inherent in glaucoma management. The five to fifteen minutes we allocate to each patient during a clinic contrasts remarkably with the ten to forty-year time-frame required for ocular hypertension to develop into significant open-angle glaucoma. Remember, 95 percent of confirmed glaucoma patients progress slowly while maintaining good visual acuity (1).

Indeed, UKTGS data show that two-thirds of patients have no progression during two years without treatment, and EMGT studies reveal that one-third exhibit no progression in seven years (2). Furthermore, where progression occurs it is often largely limited to one eye; hence, binocular vision compensates for the monocular deficit such that patients are not impeded in daily tasks.

Even end-stage glaucoma patients often function well in standard life tasks (3). Given these statistics, why are we labeling healthy people as “glaucoma suspects,” thereby making them worry about blindness for the rest of their lives? It would be far better to use our limited time with each patient to truly understand their needs, to explore their attitude to the risk of progression and to share what we know of the actual likelihood of progression.

How might we change things? A critical part of the answer is to recognize our own limitations. We should accept and admit that we have no idea which patients will progress and which will not; that we have no insights into the plot of a given individual’s glaucoma story. All we can do is talk about the present in the context of the past – and, in doing so, we are influenced by our inherent biases, habitual thought patterns, and our experiences of previous decisions (4). Thus, our insight is no more than hindsight, and is of limited value in determining which patients are at risk of blindness.

It is clear that we do not make clinical decisions on the basis of knowledge alone; my own experience suggests that conformity, bias, expectation, distraction, and fatigue all influence us significantly. Of these factors, unconscious bias may be particularly problematic. It seems to be hard-wired into humans, perhaps because in many circumstances it is an efficient way of operating. The ability of unconscious bias to skew glaucoma management is exemplified by confirmatory inaccuracies in cup-to-disc ratio (CDR) assessments (see box "It’s hard to see what’s before our eyes").

Conversely, Swedish studies – in which “experts” examined the same disc images on multiple occasions – reported marked variability in a given expert’s descriptions of a given image (5). In other words, people can’t even confirm their own CDR assessments when shown the same images at subsequent times! These kinds of observations have led me to conclude that only CDR changes of 0.2 or more should be taken to indicate genuine changes in disc morphology.

- A patient was examined at a glaucoma clinic over 20 times: first by a consultant, next by several registrars, then by some middle-grade doctors and finally by a new junior doctor

- All clinicians noted that the patient’s CDR was 0.7 – except for the new doctor, who recorded a CDR of 0.3

- Instant reaction: the outlier CDR reading must be an error made by an inexperienced, newly qualified doctor

- Subsequent observation: the actual CDR was indeed 0.3; therefore, only the junior doctor had been sufficiently free of bias or influence to record what he actually saw

- This example illustrates how an opinion – especially one held by a senior individual – can gather increasing credibility as more individuals conform to it, regardless of its actual basis in fact.

Similar problems arise in the field of IOP measurement (see box "IOP – Who Decides What’s Safe?"). We assume that instruments are correctly calibrated and good technique is always applied, it is clear that IOP readings are not reliable, but nothing is written as to how the reading can be influenced by the observer’s expectations (6). An objective pressure reading therefore requires the observer to be ignorant of previous readings.

The point is that our observations and actions are inconsistent and easily influenced by factors that have nothing to do with what is actually in front of our eyes; in fact, it is a humbling experience to realize just how wrong one can be and how often!

- Textbook guidance for new doctors suggests that IOP over 21 mmHg requires treatment

- Doctors who are guided by experience rather than textbooks, however, would probably be more concerned by IOP over 25 mmHg, and certainly by pressures over 30 mmHg

- At the same time, most experienced glaucoma physicians will have seen patients who – despite having “safe” IOP levels of 14-20 mmHg – nevertheless have significant or advanced glaucoma

- Furthermore, recent studies indicate no direct correlation between IOP and glaucoma and analysis of historical case data shows that progression predictor calculators have poor-to-zero correlation with actual outcomes (7)

- Similarly, it is known that some glaucoma cases progress despite pressure reduction, and some remain stable without IOP reduction therapy

- Therefore, although high IOP can be a legitimate concern, it does not directly predict glaucomatous change

- This “gray area” gives plenty of scope for clinical decisions to be influenced by factors, including unconscious bias!

Unsurprisingly, clinical decisions made on the basis of flawed observations and limited knowledge are substantially imperfect. For example, a physician whose clinic starts with a patient exhibiting complete loss of field in one eye, advanced losses in the other, and a pressure profile that has always been below 25 mmHg is likely to work to a relatively low “treatment threshold” for the rest of that clinic.

By contrast, a physician whose first 15 or 20 patients have no significant field loss is likely to have a higher treatment threshold – possibly a lower limit of 25 or even 30 mmHg. The same patients may be managed differently according to which other patients their doctor has seen that day.

This kind of questionable decision-making persists throughout the glaucoma management timeline. Notably, a 15-year audit in Glasgow found that only 7 percent of therapy changes were related to evidence of progression; most were due to drug intolerance or to a perception that IOP had been insufficiently lowered. This statistic raises a question: if 93 percent aren’t progressing, why were they prescribed drugs? It’s difficult to claim that we are managing their risk of progression when, as noted, we don’t know what that risk is for any given patient.

How about an example from personal experience? As a registrar, I saw a man who – having occasionally had pressure slightly over 21 mmHg – had been on drops for six years. He believed he had glaucoma, yet he had fully healthy discs and full visual fields. As his pressure was below 20 mmHg, I suggested to him that he was fine and should stop applying drops. But five years later, as a consultant, I saw him again; he still believed he had glaucoma, and was now on two types of drop – but still had full visual fields and healthy discs!

So, at various points in the past, his physicians had decided he required treatment, undoubtedly on the basis of a mixture of knowledge and feelings. The mixture might have included the following propositions: IOP is the only modifiable glaucoma-associated factor; doctors have an obligation to protect their patients; the doctor feels the patient is at risk of glaucoma, and so on. But on no occasion did anyone attempt to establish the patient’s own attitude to the risk of glaucoma progression; rather, decisions were made on the basis of the doctor’s own feelings about the situation.

Similarly, our decisions regarding surgery can sometimes be difficult to fully defend. Trabeculectomy may save vision in many cases – but, given that trabeculectomy studies typically have only a 2-5-year follow-up, we have not quantified its lifetime burden of harm. For example, we know that the risk of post-trabeculectomy blebitis and endophthalmitis is life-long, and that the results of such infection are usually blinding. I personally have seen cases of infection and blindness several years after trabeculectomy.

Cruelly, sight loss typically occurred in the eye that had the fullest visual field and healthiest disc. And I have to wonder how many myopes with tilted discs, borderline pressure, and stable, non-progressive visual field loss have undergone trabeculectomy unnecessarily. My view is that a potentially blinding operation in an otherwise stable eye should not be considered lightly; indeed, there is a significant risk that the operation will result in loss of vision far quicker than the natural history of the disease itself.

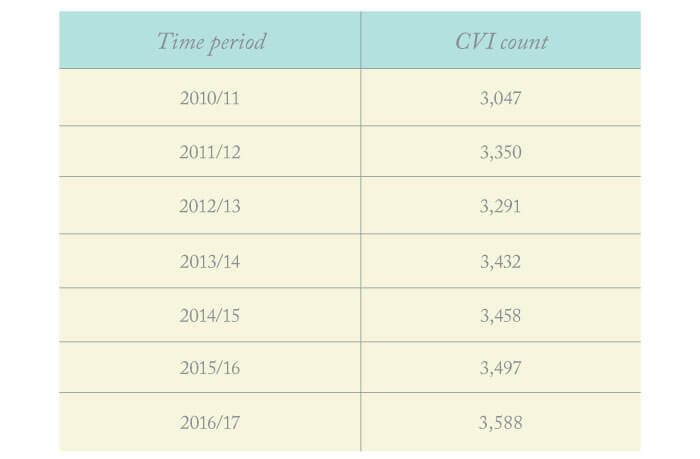

Regrettably, the last 30 years have seen no significant reduction in glaucoma-related blindness in the UK (See Table 1), despite the introduction of new treatment approaches. It seems that our best efforts make little difference to the overall glaucoma burden. Part of the issue, I believe, is continued over-reliance on pressure control for glaucoma management, despite evidence that the correlation between IOP and glaucoma is somewhat weak (unless pressure is over 30 mmHg or secondary glaucomas), and has no simple direct genetic basis.

As Richard Feynman said: “No matter how beautiful your theory is, if it does not agree with experiment, it is wrong.” It is time for glaucoma clinics to accept this, and act accordingly. Repeated studies and personal experience show IOP is not a great guide to predicting who will progress.

Patients were noted to have:

- 0.9 discs with full visual fields

- IOP >40 mmHg with no sustained progression

- IOP <14 mmHg with progressive end-stage glaucoma

- Absent temporal rim of disc but 6/5 vision (where is the foveal nerve bundle signal from?)

- Symmetrical IOP profiles (15-28 mmHg lifetime range) in the same patient’s eyes, yet one eye fully healthy and one with progressive field loss and nerve thinning

- Progressive glaucoma only after the pressure lowered with surgery.

Another part of the issue is the unreliability of the criteria we use to diagnose and monitor glaucoma. The situation is improving, in that automation helps provide more objective readings – but we must remember that even computerized systems are limited by the dataset on which they are based and by the algorithms they use for image analysis. Furthermore, automated technology remains susceptible to sources of error, such as tilt and variation in the shape of the eye or the disc.

As noted above, what we really need is a means of identifying patients at genuine risk of significant glaucomatous progression and visual field loss in their lifetime. Absent this, the emotional drive to treat all those who might be at risk of progression – in the context of a disease with a 40-year timescale – will lead to new dilemmas and cost pressures, particularly given our ageing demographic. For example, when should treatment start: immediately, or at a certain threshold of field loss, or at the earliest nasal step, or when the patient has decided their individual risk profile justifies potential side effects?

Not all is lost, however. While waiting for the development of genuinely useful predictive tools, each of us can immediately take steps which, albeit relatively simple, could make a significant difference (see box "Glaucoma: exceptional real cases").

- Revise your attitude to IOP: accept that a normal pressure is any pressure at which there is no field loss or disc damage

- Revise your attitude to glaucoma diagnosis: progression is the only evidence for glaucoma

- Be aware of your limitations: at present, it is not possible to predict the course of glaucoma in any individual

- Listen to your patients: understand their experiences and concerns, the extent to which they are satisfied with their current vision, and their attitude to the risks of glaucomatous sight loss

- Be aware that disease management decisions can easily suffer from unconscious bias. Understand your own biases, risk attitudes and decision drivers, and reflect on how these differ from those of your patients

- Tell and show your patients what you know: the Spaeth glaucoma chart is an excellent resource

- Review your patients’ understanding of what you have said.

I hope that reflection on the points I raise here will result in a new approach to glaucoma patients. For example, consider how most of us conduct consultations; the majority of our patients are relatively routine cases, and so we dispose of them with rapid, simple consultations, thereby saving our time and energy for the more difficult cases.

Obviously, it is easier to make rapid decisions that align with our previous experience than to apply sustained mental effort and remain aware of one’s own biases. But we need to take the more difficult road, if we are to provide relevant, personalized care over time-periods that are meaningful to the patient. Not least, we need to better understand our patients; indeed, I suggest that the patient should do more talking than the doctor during the consultation. We can help this process by posing appropriate questions.

For example, we might ask the patient what they know about their eye condition, what they think will happen to their vision, and what key questions or worries they have. The answers they give will help us provide useful information that each patient can assimilate and actually remember.

At the same time, we must learn to be honest with ourselves regarding our own biases and motivations; this too may help us to be more honest with patients. In fact, I believe we could make a big difference simply by replacing the misleading “glaucoma suspect” terminology with a more open and reassuring statement of fact, as follows:

“I have no irrefutable evidence that you have glaucoma today; most likely you will never have it. If you do develop glaucoma in time, the likelihood is that it won’t significantly affect your daily life. I am happy to continue to monitor you, however, and if things do change then we can discuss treatment options.”

Such an approach will help patients understand that most people with ocular hypertension don’t ever progress to glaucoma, and that early glaucoma cases often progress very slowly. And this will in turn reassure them and leave them with a better quality of life than otherwise. It will also reduce future consultation times, which is good for everyone.

When making decisions – such as with regard to potentially blinding surgery – let’s remain aware of how the decision is being made and influenced. Who has input, and what kinds of bias or influence may be swaying their decision? Ultimately, the patient should make the decision – after all, they must live with the outcome, whether their decisions are conscious or passive.

When we accept this, we will also understand that a key role of the doctor is to help each patient understand the specific reality to address, and to support each patient as he or she decides on the most suitable course of action. Doing this whilst remaining aware of, and resisting, our own biases and agendas will, I believe, significantly improve the well-being of patients who are labeled with or believe they have “glaucoma.”

References

- D Crabb, “Learning from big data and large cohorts - Big data collection from clinics”, Paper presented at European Glaucoma Society meeting, 2016, Prague, Czech Republic.

- EuroTimes, “Translating the UK glaucoma treatment study” (2018). Available at: https://bit.ly/2WuWrTB. Accessed June 10, 2019.

- WE Gillies et al., “Management and prognosis of end-stage glaucoma”, Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 28, 405 (2000). PMID: 11202461.

- Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow. Penguin Books: 2011.

- AL Coleman et al., “Interobserver and intraobserver variability in the detection of glaucomatous progression of the optic disc”, J Glaucoma, 5, 384 (1996). PMID: 8946294.

- Review of Ophthalmology, “Can You Trust Your IOP Readings?” (2011). Available at https://bit.ly/2X2oEFY. Accessed June 10, 2019.

- G Spaeth, “Target IOP – How much is enough?”, Instructional course at European Glaucoma Society meeting, 2016, Prague, Czech Republic.