I’m currently working on non-viral gene therapy, which – I believe – will be the second wave of therapies in this field. This alternative approach uses plasmid vectors, which are composed of entirely human elements that can package the gene, and deliver it to target organs. Non-viral gene therapy has not traditionally been considered as effective as the use of viral vectors because of the cell’s ability to silence plasmid vectors after a short time, meaning that they are no longer able to express the gene of interest.

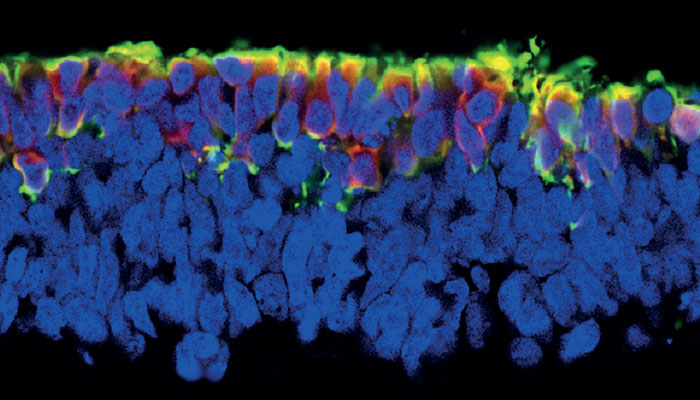

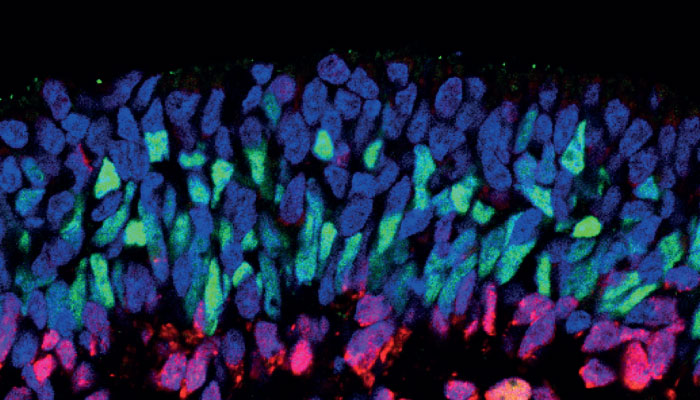

Fortunately, we have managed to find the missing ingredient: the scaffold/matrix attachment region (S/MAR). These molecules serve as anchor points for our DNA, mediating the structural organization of chromatin and playing a role in gene expression. If you place an S/MAR into the plasmid vector, it allows it to sit in the nucleus alongside our existing genome. There, it can express the gene without being silenced.

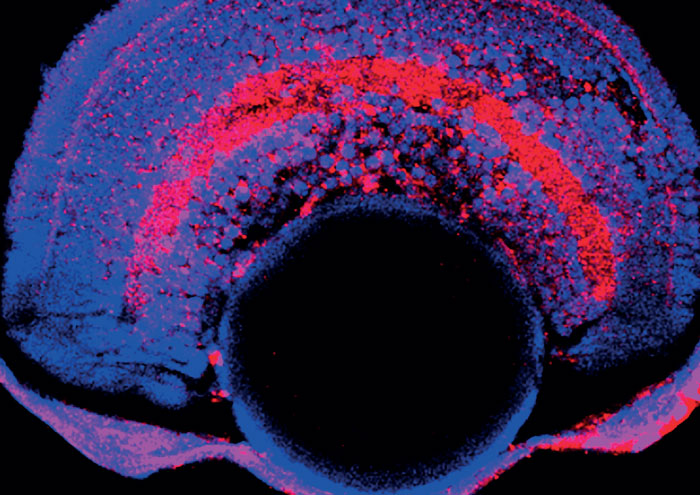

These non-viral gene therapy delivery systems are able to carry genes of any size; this is important because there are inherited retinal diseases caused by genes that are larger than the size limit of viral gene delivery (which is around 8000-9000 kilobases). A key example is Usher syndrome, the most common cause of deaf-blindness worldwide, where the most prevalent causative gene is USH2A, this is around 16,000 kilobases in size, and mutations in this gene also contribute to non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa (RP). In other words, a significant number of patients who are not amenable to gene therapies based on viral vectors could be helped with the non-viral systems.

Currently, those patients undergoing gene therapy treatments require steroids administered before and after the surgery to reduce inflammation and the risk of an immune response to the virus. Luxturna is licensed for single administration, the potential immune system response to a second dose is still difficult to predict. As the plasmids are made from human components, the chance of an undesirable immune response is significantly lower. Those patients undergoing viral gene therapy today may need a non-viral alternative in the future.

In the past, the early viral vectors integrated into a patient’s genome, sometimes resulting in insertional mutagenesis – another risk, but this is less so with newer adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors. The S/MAR plasmid vectors sit alongside our DNA in the nucleus, so there is no risk of mutations occurring.

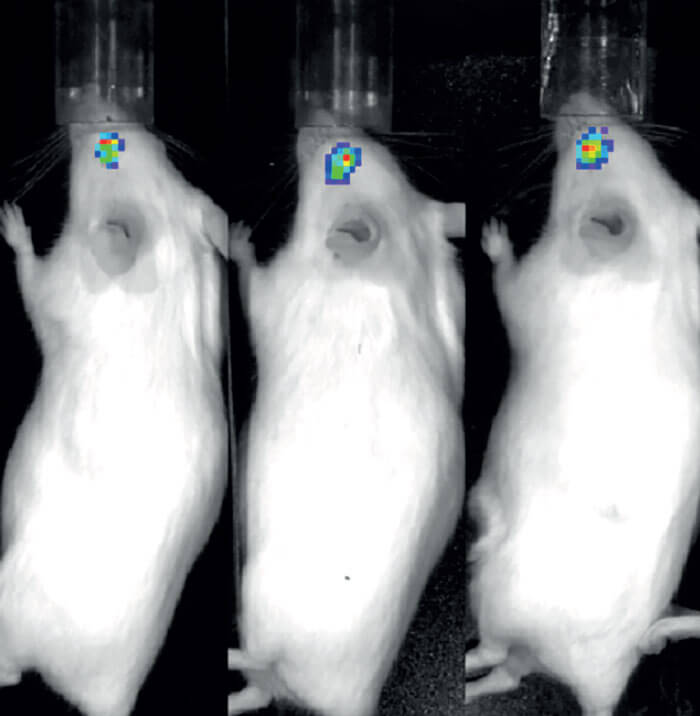

Taking these aspects of non-viral gene therapies into account, researchers consider them to be safer and more effective – and perhaps the non-viral approach will become the standard delivery system for all gene therapies in the future. But, at the moment, we are only at the preclinical stage – working with animal models and stem cells to show that they are having the required effect.

Another research area that I focus on is mutation-based genetic therapies, and in particular nonsense mutations, which are responsible for up to 70 percent of human genetic diseases. In ophthalmology, nonsense mutations can account for between 30-50 percent of cases in some disorders, such as aniridia, choroideremia, RP and Leber congenital amaurosis. We have been testing a range of small molecule drugs with the ability to bind to our ribosomal protein-making machinery; if it comes across a nonsense mutation, it helps override this and form a functional protein. The results of our preclinical work on applying these drugs to the field of inherited retinal diseases has now been published, and we are in the process of moving into clinical trials.

The ophthalmic gene therapy field is extensive, and research is moving at an incredible pace. The networks developing between scientists and clinicians are really strong, and there is a great feeling of working together to develop a smooth pipeline for the translation of these therapies.