- The UK-based charity, Fight for Sight was founded back in 1965 by the country’s first ophthalmic pathologist, Norman Ashton

- Fight for Sight has funded a number of breakthroughs in ophthalmology in the last 50 years

- The charity funded David Spalton’s work on square-edged IOL designs that have dramatically reduced rates of PCO following cataract surgery

- Some of the discoveries, such as the function of the gene that causes choroideremia, CHM, has led to the development of gene therapies, currently in clinical trials

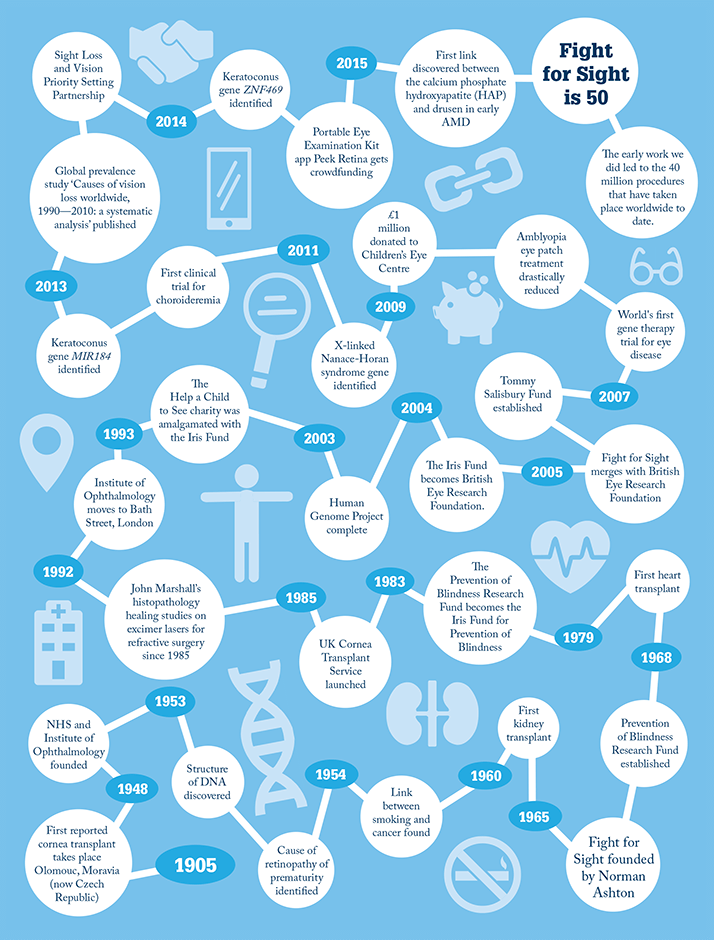

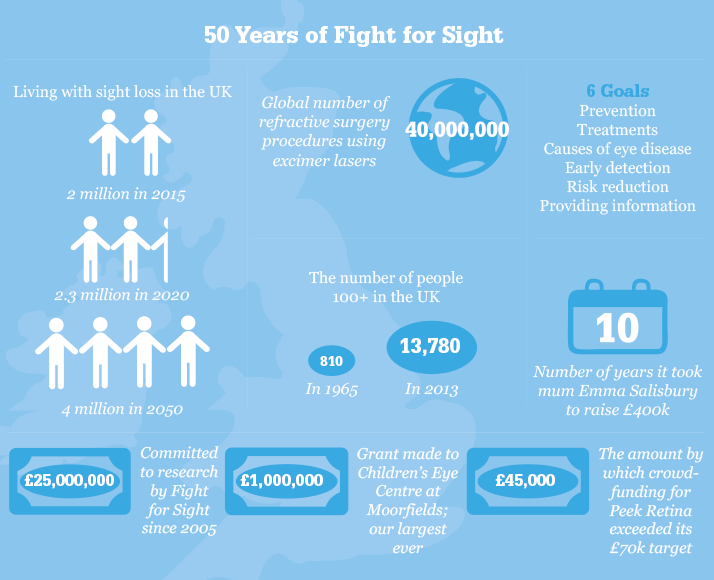

Fifty years ago, the United Kingdom was a very different place. Its National Health Service (NHS) was a teenager and the population was booming with post-war babies. Just 810 of its 54 million people were centenarians – compared with 13,780 in 2013 – and only seven years had passed since Watson, Crick, Wilkins and Franklin had discovered the structure of DNA. Fifty years ago also saw the foundation of the British charity Fight for Sight by the UK’s first ophthalmic pathologist, Norman Ashton. Born in 1913, Ashton qualified in medicine in 1939, just as World War II began. In 1948 he was invited to be Director of Pathology at Moorfields Eye Hospital and the newly created Institute of Ophthalmology at the University of London, a post he held for 30 years. It was in 1965 that he founded Fight for Sight to provide funding for the Institute of Ophthalmology. “Ophthalmology was of little interest to most pathologists,” says Michèle Acton, Chief Executive of Fight for Sight. “But Ashton believed that a ‘complete pathologist’ must also undertake research to understand the nature of disease.” From his laboratory, Ashton published over 200 papers and trained numerous ophthalmic pathologists who dispersed around the globe.

Nineteen sixty-five also saw the Royal Eye Hospital League of Friends establish the charity Prevention of Blindness Research Fund. Following successive rebranding (first as the Iris Fund for the Prevention of Blindness, then as the British Eye Research Foundation), it merged with Fight for Sight in 2005, creating the largest UK national charity dedicated to funding eye research. An early research breakthrough stemmed from Ashton himself. In 1953 he discovered that high levels of oxygen, given to help premature babies breathe, disrupted retinal blood vessel growth. Retrolental fibroplasia (now retinopathy of prematurity) was a major cause of blindness in the UK. Ashton’s work led to controlled oxygen delivery, saving the sight of many. The charity has been instrumental to several significant landmarks via the basic steps that underpin new fields of research. In the 1970s and '80s, for example, when laser refractive surgery emerged, the Iris Fund supported Moorfields’ John Marshall to help develop it. “This was a brand new technique so we needed to find out how different eyes would respond, whether myopic, hypermetropic or astigmatic,” says Marshall, now at the Institute of Ophthalmology at University College London (UCL). “The early work we did led to the 40 million procedures that have taken place worldwide to date.” The Fund also supported David Spalton’s work at St Thomas’ Hospital, London, as he and his research colleagues investigated the effects of a square-edged intraocular lens (IOL) design on posterior capsule opacification (PCO) rates. They discovered that the physical pressure of such an edge provides a physical barrier to lens epithelial cell migration, preventing PCO after cataract surgery. “Our work had a fundamental influence on the design of the lens,” says Spalton, now retired from the NHS but still active in research and consulting. “The lens won international recognition and improves visual outcome for millions of patients each year.”

The next sequence of events

In 2003 the Human Genome Project was completed – arguably the most important body of biological knowledge we’ll ever have. Almost every field of biomedical research gained momentum from the task begun over a decade earlier to map the entire genome of Homo sapiens. Finding the causative genes behind inherited disorders became possible.Following the discovery that mutations in the gene RPE65 cause Leber congenital amaurosis in some children, we helped fund the team responsible for the world’s first clinical trial of gene therapy for eye disease. Knowing the right gene for Nance-Horan syndrome, for example, also means that families can be given a precise molecular diagnosis and realistic genetic counselling. The advent of next-generation DNA sequencing to scan multiple regions simultaneously (rather than sequentially mapping one locus after another) makes this faster and easier – and this is how our teams discovered two key genes implicated in the development of keratoconus. It’s not all about the double helix, though. Our researchers at Queen’s University Belfast have significantly advanced bone marrow-derived stem cell therapy for diabetic retinopathy. We funded the research underpinning the discovery that children with amblyopia need only wear an eye patch for three months – for only a few hours a day – to bring the “lazy” eye up to speed, rather than all day for years.

Landmark research

January of this year brought news of an unexpected potential trigger for AMD: its hallmark, drusen, form early in the disease process, and do so around rogue spherules of hydroxyapatite – the form of calcium phosphate found in teeth and bone mineral. This was huge news, providing a clear target for treatment and a biomarker of disease status. Imre Lengyel, the project’s lead at UCL, is partially funded by Fight for Sight. An organization without statutory funding must make a little go a long way. Donors want to fund research, not university overheads – but the latter are part of the full cost of research. Happily, universities can claim a top-up from the government’s Charity Research Support Fund – up to 26 percent across all awards – if the call involves open competition and peer review. So that institutions can access this additional resource, our funding process involves both. We have committed £25 million to eye research in the past decade. To increase our impact, we often co-fund. The award-winning prevalence study ‘Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990—2010: a systematic analysis’ was part-funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and others; Fight for Sight paid for the data analysis. One of our most rewarding lines of research has been in choroideremia. Super-supporter Emma Salisbury approached us to set up the Tommy Salisbury Choroideremia Fund when her son, then aged 5, was diagnosed with the condition that threatened to blind him by the age of 40. Ten years and £400,000 later, a treatment for choroideremia may be in sight. Emma’s contribution helped enable Miguel Seabra at Imperial College London to track down the function of the protein produced by the causative CHM gene. This led, via collaboration with a leading retinal surgeon and additional funders, to a successful Phase I gene therapy trial. Now startup biopharmaceutical company Nightstar has attracted a £17 million investment from Wellcome Trust subsidiary Syncona to get the treatment to clinic.Innovation is everywhere Andrew Bastawrous, a lecturer and ophthalmologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, used our clinical training fellowship (co-funded with the UK’s Medical Research Council) to take him across Kenya gathering data on the incidence and progression of conditions such as AMD and glaucoma. Inspired by this logistically difficult task, Bastawrous launched the Peek project to develop a smartphone app toolkit for ophthalmic telemedicine. Last November, the Peek team launched a crowdfunding appeal to raise extra cash for manufacture and distribution. It worked. To date, they’ve exceeded their £70,000 target by over £45,000. Attention is shifting from researchers to patients in terms of who decides what gets funded. With guidance from the James Lind Alliance, we partnered with The College of Optometrists, NIHR, RNIB, the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth), and Vision 2020 on the 2013 Sight Loss and Vision Priority Setting Partnership. “We thought it hugely important, given such limited resources for research and so many unanswered questions, for research funders to understand how patients, carers and eye health professionals prioritize these questions so that future research can be targeted accordingly,” says RCOphth CEO, Kathy Evans. Now we aim to encourage UK funders of eye research to include the priorities in their grant application process. The challenge is to ensure that researchers are neither deterred from working outside the priorities where there is scientific merit, nor paying lip service to them in a bid for limited funds (as we can only afford one in six projects).

Where next?

It’s impossible to predict the state of eye research 50 years from now. Stem cell research may have long since fulfilled its potential for human self-repair. Who knows where 3D printing will take us? Germline gene therapy might even eradicate inherited eye disease altogether, assuming the ethical considerations can be met. We will surely have treatment for dry AMD; a one-off fix for glaucoma. But what would our vision – a future where everyone can see – really look like? “Our family has always known about sight loss,” says Emma Salisbury. “My granddad had choroideremia too. As kids, we learned how to help him. We let him know what was on his dinner plate by describing a clock face – your meat is at 12 o’clock, the potatoes at 4 – but he couldn’t really play with us.

“I don’t want Tommy’s life to be like that. He already has difficulty seeing when it’s dark. I know there is now hope, but I won’t stop until I know Tommy will always be able to see me and see his own children.” How many causative genes are out there, unidentified? We don’t know. Even when a gene is identified the pathway to pathology may be oblique. “In some retinal diseases, the mutation is known, but how this causes disease and why one mutation can result in varying severity is not understood,” says Omar Mahroo, Fight for Sight researcher and academic clinical lecturer in ophthalmology at King’s College London. “Better understanding of the retina at a cellular and molecular level, and of how genetic and environmental factors interact there, would help guide treatment or predict responses to treatment. This is very important. “In the long term, previously untreatable diseases can become treatable. Existing treatments can be applied where they are more likely to work and less likely to harm. This would both improve quality of life for future patients and reduce the wider financial burden of untreated eye disease.” Never has the pace of change been faster. People who might once have been sent home from the clinic and told nothing could be done now have options or at least some hope. “At the moment we have six goals”, says Michèle Acton. “We fund research to help us understand the causes of eye disease, to enable earlier diagnosis, to develop ways of preventing sight loss, to bring new and better treatments to the clinic, and ultimately to restore sight to those who have lost it. We also believe it’s extremely important to inform people affected by sight loss about the things we learn. “Over time, our goals will need to adapt to new treatments reaching the clinic, a changing research landscape, an aging population and a potential doubling of the number of people with sight loss in the UK. But we will always continue to invest in research wherever we can have greatest impact and leverage. In the best case scenario we’ll soon be out of a job.”

Ade Deane-Pratt is Fight for Sight’s Research Communications Officer.