- Surgeons planning refractive surgery should be certain that the patient does not have a predisposition to keratoconus

- Genetic testing for corneal dystrophy is widespread, but keratoconus is a much more complex condition

- The research into keratoconus genetic screening is promising, and data will become more precise as more information is included

- The ultimate goal is to develop a test available for every potential keratoconus patient, which will become an inexpensive industry standard.

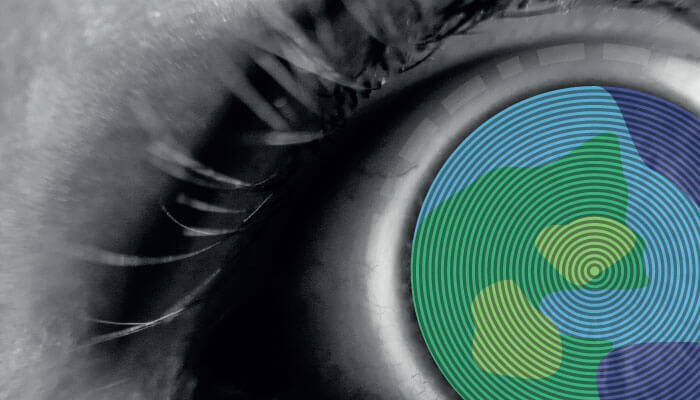

Eyes may appear perfectly normal, yet be predisposed to serious conditions – some of which can be triggered by medical intervention. It follows that the ability to screen for such predispositions would be very useful, particularly where elective surgery is being proposed. Keratoconus (KC) is a classic example – if you are offering a patient refractive surgery to achieve spectacle-free vision, you want to be certain that the eye is not prone to KC. Also, if you are looking for early indicators where family history exists, or in patients with corneas that high dioptric values or astigmatism, you want to be able to catch them as early as possible. But is KC screening a realistic option?

Important considerations

To answer that question, we can look at some other disorders where genetic screening is now the norm. Corneal dystrophy, like KC, can be triggered by refractive surgery or eye injuries; unlike KC, however, testing for corneal dystrophy is increasingly widespread. This is because corneal dystrophy is a well-characterized monogenic disorder, and screening is therefore very simple: we know that if the patient has no keratoepithelin mutations, we can safely proceed with the surgery. But KC is far more complex than corneal dystrophy; can we develop a useful screen for this condition? I think we can; consider, for example, breast cancer, the genetic complexity of which is not dissimilar to that of KC. We know that mutations in the BRCA gene are strongly associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. It is also true, however, that not all breast cancers have a known genetic etiology, and only some of those that do will fall into the BRCA camp. Nevertheless, BRCA screening is useful to guide treatment choices in breast cancer management.

Given the above, it doesn’t seem unrealistic to expect that we will get to a similar position with KC, and we are certainly actively working towards that goal. The research is still at an early stage, but extremely promising – we’ve already found over 300 variants within 75 genes that are strongly associated with KC. The data will only get better as we look at more and larger populations, and as we add hundreds of genes – and thousands of mutations – to our screening panels. Incidentally, I believe it is particularly important to include, as we are doing, a broad range of ethnicities in this work, because our experience is that the genes and mutations most commonly implicated in KC differ from population to population. This kind of information is very important for us at Avellino Labs – if we’re going to develop a genetic test applicable to a given geographical area, we need to be sure that it will catch the mutations typical of the people in that area.

Looking to the future

Our long-term goal is to develop a product that could be used to screen every patient potentially at risk for developing KC – those with family history, contact lens candidates, refractive surgery candidates, and those patients with corneal shapes that are steep or questionable upon exam. Of course, providing a universal KC test at a price that is both commercially viable and acceptable to the market will require economies of scale – and that is what we are working towards. We want the test to become a standard that physicians agree upon, and not be prohibitively expensive. Genetic testing has not had consistent success in the eye care industry, but to get an idea of the likely adoption pattern of a KC test, we should look to the uptake of the corneal dystrophy test.

At first, many surgeons were resistant to the product; they would claim, for example, that they didn’t need a genetic test for the corneal dystrophy because they “know it when they see it.” But now, as more physicians are seeing patients with the disease, they’re increasingly accepting that actually it’s better to confirm than not, especially as the patients themselves are more and more aware of it. Patient health and safety should always be the primary concern, but as genetic testing for conditions becomes more mainstream for all areas of healthcare, screening will eventually help reduce litigation risks.

Today, our focus is on the benefits to the patient. A genetic screening test allows early identification of at risk patients, which empowers both the physician and the patient with information, allowing better treatment decisions and lifestyle changes. Often, you can avoid the more complex KC procedures – transplantations and so forth – by choosing specific vision correction procedures or getting the patient into a monitoring program and using treatments like cross-linking. Even simple lifestyle changes, like actively managing inflammation and making the patient aware of the dangers of eye rubbing can help reduce progression in patients.

Mainly due to an increased awareness of the prevalence of KC in the world, we expect to see a much faster uptake for the KC test than what we saw for the corneal dystrophy test, in fact, it’s difficult to find reasons not to apply a KC test. I certainly don’t anticipate any ethical issues. Our genetic test will screen for particular KC-associated genes and mutations that are specifically associated with KC. As with any genetic test, physicians and patients need to work together with a genetic counsellor to understand the implications of the data that is being provided, and how it may change over time. Overall, the advancement of precision medicine and use of AI tools in eye care is something to be excited about, and as physicians use them more in their practice, they will become more comfortable having these types of discussions with patients. Ultimately, that will mean better care through earlier detection, which I know physicians are excited about.