In March 2020, I joined a group of highly trained surgeons and select members of the medical community – mainly ophthalmologists – on an expedition through the Amazon. The aim: to restore sight and prevent blindness. The Instituto da Visão-IPEPO from São Paulo, Brazil, provides cataract surgical services, free glasses, and tertiary eye care to cover a population of over two million people in metropolitan São Paulo, the Amazon, and beyond, with the use of telemedicine and other innovative technologies.

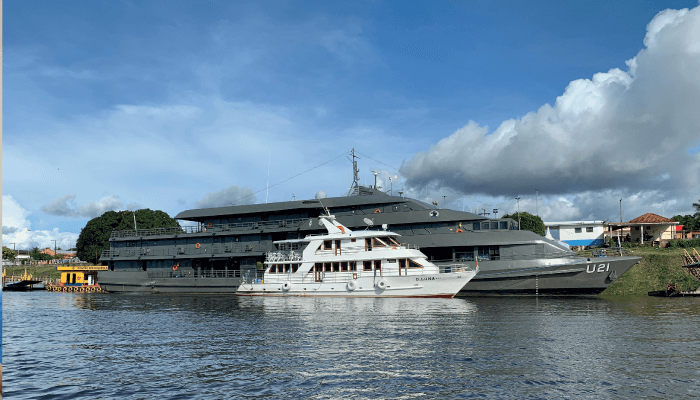

The project “Oftalmologia humanitaria” was founded by Rubens Belfort Jr., Head Professor of Ophthalmology at the Federal University of São Paulo. Belfort, along with Jacob Moyses Cohen, Professor of Ophthalmology at Federal University of Amazonas in Manaus, Brazil, usually organizes two or three expeditions a year, each time to a different place in the Amazon – typically, supported by the Brazilian navy, and the ophthalmic industry. Notably, the project received the 2019 Antonio Champalimaud Vision Award, which has the support of The Right to Sight – an initiative in collaboration with the World Health Organization and the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness.

The single greatest cause of blindness in developing countries or remote locations with little to no access to medical care is cataract (see Figure 1). In places with high UV radiation, pterygium also has a huge impact on decreasing vision. Uncorrected refractive error, including presbyopia, is also major cause of sight deterioration. And so, during our expedition through the Amazon the goal was to perform cataract and pterygium surgery, use telemedicine to check for glaucoma by evaluation of the papilla, and distribute glasses. I was told that the surgical program worked in three steps. The first step: preselection of patients by the residents at the Cohen clinic in Manaus; the second step: the surgery itself; and then, some days later, we would arrange another visit – the third step – to check for postoperative complications, which would be treated in Manaus, if necessary. The Cohen clinic is operated by Jacob Cohen and his son Marcos Cohen. Marcos, a highly experienced surgeon, taught me a lot, mainly in the field of pterygium surgery.

The mission was only a short one – lasting four days – so we used a smaller boat, without the support of the navy, to travel to Urucara and Parintins. Parintins is a municipality in the far east of the Amazonas state in Brazil. The city is located on Tupinambarana Island on the Amazon River, and the population of the entire municipality is around 115,000. Uracara is much smaller. Both places have small hospitals, but no ophthalmology services, and the 16-hour boat journey to the large hospitals in Manaus is not affordable for the majority of the population.

The trip started at the international São Paulo Guarulhos airport. I was surprised not to see any locals at the gate five minutes before boarding time. But I quickly learned some cultural differences: in Germany time might be measured in minutes, in Brazil it is hours, but in the Amazon, it’s days! After a four-hour flight we arrived in Manaus, the capital of Amazonas – and the only city in the world with two million inhabitants that can be reached only by airplane or boat. We boarded our boat, the D. Luna, and sailed through the night; we were supposed to arrive at our first stop and start surgery the very next morning at 7am. During that first evening, I was introduced to the crew and the team, which included highly honored members of the ophthalmological community, such as Rubens Belfort and Alfred Sommer, a professor of epidemiology and ophthalmology, and former dean of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who dedicated his life to blindness prevention strategies, child survival, and public health. Also on board was Miguel Burnier, a professor of ophthalmology, pathology and oncology at McGill University in Canada and President of the PAAO (Panamerican Association of Ophthalmology), who was an inspiring teacher.

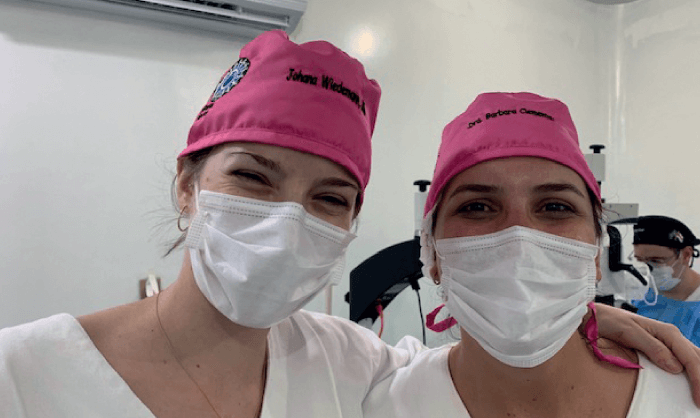

My bunkmates were two medical students, Laeticia Ettinger and Laura Nishimura, and Barbara Clemente, one of the younger surgeons, who has since become a great friend and teacher; she had just finished her surgical fellowship with Belfort. The four of us occupied two berths, so we were forced to get to know each other quickly; luckily, we got along really well.

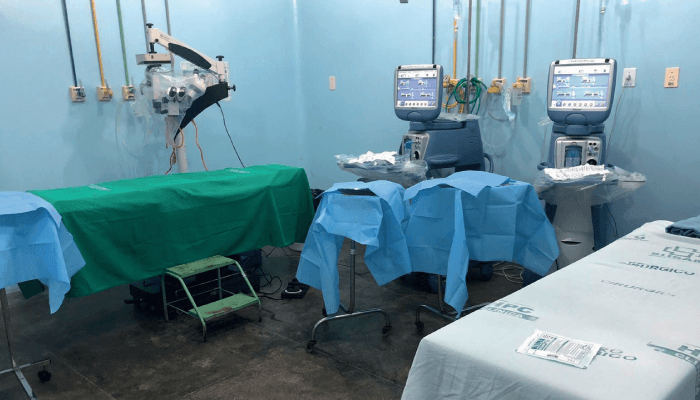

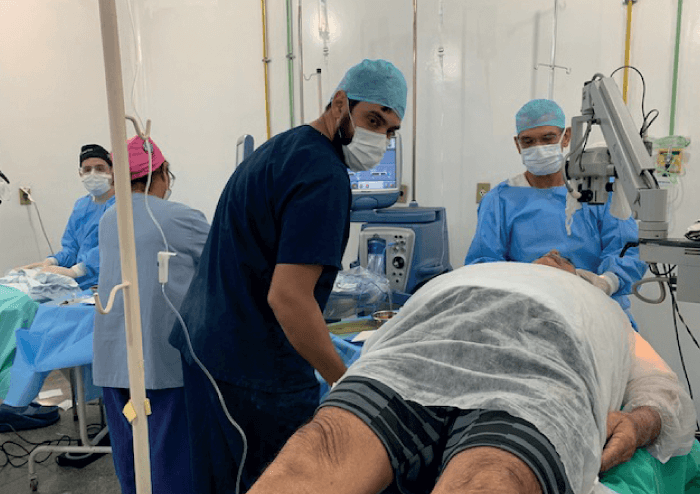

We arrived at Urucara at noon, welcomed by the city mayor, and began to set up the equipment for surgery. We brought boxes containing the IOLs, reading glasses, surgical material, and phaco machines. Patients had been waiting for us patiently since 4am, but there were no complaints, just smiles and words of gratitude. That day, we performed around 50 surgeries, finishing around 10pm. All surgeries were supervised by the anesthesiology team members: Lenilson Moreira and Gustavo Saraiva. All patients received an IV-free, sublingual sedation, and topical – and if necessary peribulbar – anesthesia. After the first day we had to pack everything up again, and we sailed to Parintins, where we arrived the next morning. We spent two days there, and performed 100 cataract procedures.

The surgical team included four surgeons: Lincoln Freitas, Fernando Drudi, Marcos Cohen, and Barbara Clemente, as well as two technicians. I watched numerous surgeries over a couple of days, and Lincoln Freitas devoted a day to teaching me how to perform surgery step by step. He has a vast experience in anterior segment surgery, but he is also an incredibly calm and patient teacher, and he taught me the 12 steps of cataract surgery back to front, as every potential mistake has an impact on the surgery, and makes it more difficult. We started with the removal of Healon from the anterior chamber after IOL implantation, and finished with capsulorrhexis, the early but decisive step.

Operating conditions in the Amazon were (unsurprisingly) very different to the hospitals I had worked in, but it was amazing to see that it is possible to practice responsible medicine using simple means, sometimes it called for creativity.

What struck me the most were the interactions between medical staff and patients: everyone talked to each other in a very warm, heartfelt way. We felt united under a common cause.