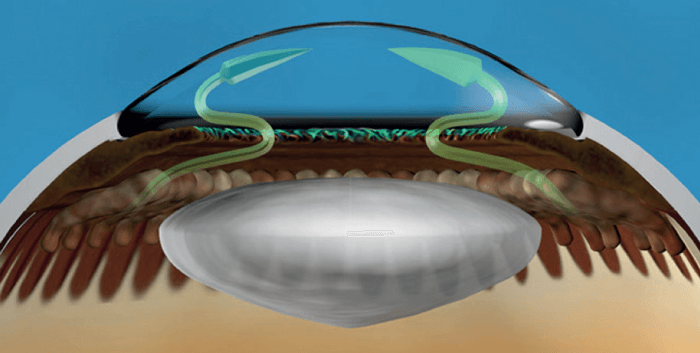

Figure 1. ECP is an aqueous inflow reducing procedure. Combining ECP with other outflow procedures offers a balanced surgical solution for the patient that follows the same line of thinking used when offering inflow and outflow medications.

At a Glance

Although pharmacologic treatment remains the backbone of glaucoma therapy, there has also been incredible innovation and growth in the surgical device arena, not least MIGS

Though it is common for a patient to be on a number of topical medications, it is not common practice to combine more than one MIGS procedure to achieve the same end – though perhaps it should be

Combining procedures – such as ECP with the iStent (3) – makes sense; there is a growing body of real-world experience, both in terms of efficacy and safety

Though a practice still very much in its infancy, combining procedures should be given the same consideration afforded to the combination of pharmaceutical agents with different mechanisms of action.

The most common first-line medical treatment for glaucoma is a prostaglandin analog eye drop. In addition to prostaglandins, beta-blockers, alpha-adrenergic agonists, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and other traditional medications, we now have new pharmacologic additions, such as nitric oxide-donating compounds, Rho-kinase inhibitors and a variety of fixed combination options. In total, there are around nine different classes of glaucoma medications from which physicians mix and match to get a patient to their target intraocular pressure (IOP). An effective and useful strategy is to combine medications with different mechanisms of action to achieve an additive effect.

Although pharmacologic treatment remains the backbone of glaucoma therapy, there has also been incredible innovation and growth in the surgical device arena. Some of the procedures, such as the iStent Trabecular Micro Bypass (Glaukos), have safety profiles that arguably compare favorably to the side effects of topical medications. And yet, though it is common for a patient to be on a number of topical medications, it is not common practice to combine more than one minimally invasive glaucoma surgical procedure (MIGS) to achieve the same end. I would argue that this strategy should be considered more frequently.

Affirmative action

In the same way that we combine topical hypotensive drops to impact inflow and outflow in a sequential approach to strengthening therapy, we can combine MIGS procedures to augment IOP control; this can be in the form of multiple similar devices or by combining devices with different mechanisms of action. The procedure I have performed most commonly to reduce aqueous inflow is endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP). The ab interno procedure shrinks and effaces the ciliary processes in a controlled and titratable manner, resulting in an effective reduction of aqueous humor production. A review of several published studies of ECP shows a reduction in IOP between 18 percent and 47 percent in patients across the spectrum from moderate to severe disease states (1).

I feel that it is most beneficial to treat a full 360 degrees of the ciliary epithelium, applying laser both to the ciliary processes and the intervening crypts. I use the EndoOptiks E2 laser and endoscope system (Beaver-Visitec International, Inc.); I prefer a curved probe, which allows me to treat approximately 270 degrees through a single incision, then treat the remainder of the ciliary ring via a second incision. The laser is generally set between 200 and 300mW and the ciliary processes are treated sufficiently to cause them to shrink and whiten, but not to pop. Though the safety profile is favorable (2), it is necessary to plan for inflammation following ECP. An intracameral steroid at the completion of the procedure is ideal, and I generally prescribe frequent post-operative steroid drops and topical NSAIDs as well.

In combination with ECP to reduce aqueous production, it is possible to use any of a number of MIGS procedures aimed at improving aqueous outflow. iStent and Hydrus microstent (Ivantis) can augment trabecular outflow, while Trabectome (Neomedix) or Kahook Dual Blade (New World Medical) can be used to remove trabecular meshwork to bypass the traditional outflow pathway. The rational combination of ECP with the iStent has already been described in the literature (3); there is a growing body of real-world experience with both techniques in terms of both efficacy and safety.

iStent and beyond

The release of the iStent inject has only increased adoption and success with this device. The iStent inject system deploys two separate stents, increasing the probability of accessing the collector channels. Studies have shown that placement of multiple stents does positively titrate treatment (4), and the new device also eases implantation with a direct, perpendicular approach to the trabecular meshwork, rather than circumferential; iStent designs continue to evolve in an attempt to further improve efficacy. The Hydrus microstent also aims to improve the traditional outflow system, dilating and scaffolding Schlemm canal to augment outflow of aqueous humor. The 8-mm-long Hydrus spans an entire quadrant, potentially providing access to numerous collector channels in this region, but there is not as much clinical experience with this newer device as with iStent.

Goniotomy performed using the Trabectome lowers IOP by selectively removing the trabecular meshwork and inner wall of Schlemm canal from 90 to 120 degrees of the nasal angle. This device uses a micro-electric cautery system. The Kahook Dual Blade is a similar, minimally invasive but single-use approach, providing aqueous direct access to the collector channels and distal outflow system by removing a section of trabecular tissue procedure; real-world experience is less.

The suprachoroidal space provides a further potential drainage route, analogous in some ways to the uveo-scleral outflow route promoted by some medications. The CyPass (Alcon) was the first device to work in this way but has recently been withdrawn over concerns regarding adverse effects on the corneal endothelium. For some clinicians this setback sounded a precautionary note over widespread early adoption of new technologies, though for most experienced surgeons it merely reinforced the need for a full and candid discussion of the risk-benefit ratio of any form of surgical intervention.

Evidently any surgical procedure has risks, but MIGS procedures generally have fewer serious complications than traditional penetrating surgery, making them more attractive for both patients and surgeons than a trabeculectomy, at least in the early stages of treatment. When we combine one of these new approaches to increasing aqueous outflow with ECP, still the only widely-available treatment to decrease aqueous production and secretion, we have highly effective glaucoma treatment with an excellent safety profile.

Consider combining

It behooves those planning healthcare to ensure that any new procedures are both clinically- and cost-effective before widespread adoption, particularly in areas of nationally funded health services. When considering clinical and financial benefit, some have expressed concerns over the cost of MIGS outflow procedures compared to their efficacy, especially when stacked up against the relatively low cost of topical drugs in the UK. In this regard it is important to consider not just high device costs (iStent, Hydrus) but overheads, such as initial setup (ECP, Trabectome), and savings afforded by using MIGS, consequent upon reduced need for follow up consultations compared with traditional surgery (trabeculectomy or tubes).

MIGS in general, and ECP in particular, are enjoying a quiet crescendo as surgeons realize that they can add these procedures to phacoemulsification in patients with combined cataract and glaucoma for little extra cost; indeed, if one factors in reduced need for follow-up consultations compared with trabeculectomy, MIGS procedures may work out ultimately to be more cost-effective.

Combining MIGS inflow and MIGS outflow procedures is still very much in its infancy in Europe, and I acknowledge that it is not currently widely accepted. But when it comes to evaluating efficacy, I believe that combining an inflow and an outflow procedure should be given consideration in a manner analogous to the combination of pharmaceutical agents with different mechanisms of action.

References

- K Kaplowitz et al., “The use of endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation for moderate to advanced glaucoma”, Acta Ophthalmol, 93, 395 (2015). PMID: 25123160.

- L Seibold et al., “Endoscopic Cyclophotocoagulation”, Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol, 22, 1, 18 (2015). PMID: 25624669.

- T Ferguson et al., “Microbypass stent implantation with cataract extraction and endocyclophotocoagulation versus microbypass stent with cataract extraction for glaucoma”, J Cataract Refract Surg, 43, 377 (2017). PMID: 28410721.

- L Katz et al., “Long-term titrated IOP control with one, two, or three trabecular micro-bypass stents in open-angle glaucoma subjects on topical hypotensive medication: 42-month outcomes”, Clinical Ophthalmology, 12, 255 (2018). PMID: 29440867.