In the past seven or eight years, I have treated more than 1,000 eyes with corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL), first as part of the CXL-USA study and later with the Avedro KXL system. The majority of these cases have been typical patients with progressive keratoconus – older teens and adults in their 20s and 30s — but it is worth discussing how to address less common CXL cases that surgeons may encounter.

Younger or very anxious patients

Young patients — and very anxious or claustrophobic adults —benefit from what I like to call “verbal anesthesia,” or a steady stream of reassurance that they are doing great, the procedure is going well, and so on. It can be very helpful for an anxious patient to be allowed to have a parent or other loved one in the room as a comforting, reassuring presence – perhaps even holding their hand throughout the procedure. We have a sound system in the treatment room so that patients can choose their own Pandora music station to help them relax.

Patients with intellectual disabilities

Patients with autism and other intellectual disabilities have been among my most difficult cross-linking cases — not because of any clinical aspects of the case, but due to the communication challenges and difficulty gaining the patient’s cooperation. Creativity may be required. One author recently reported on a case of a teenager with Down syndrome whose father held a tablet computer just behind the UV light to help the child maintain fixation during the procedure (1). Patients with Down syndrome have a much higher than average incidence of keratoconus, but also may be diagnosed at a later stage than those without intellectual disabilities (1, 2).

With any patient with learning difficulties, we schedule an extra session with the patient and a parent or caregiver. This additional time gives us the chance to introduce the concept and the procedure room and practice some of the potential challenges: lying still; fixating on a light; bringing the microscope or light source over their head. The key to success with such patients is to ensure that they feel secure and cared for throughout the procedure.

With some patients with learning disabilities, it may be necessary to consider general anesthesia. The UV light source unit is portable and could be transported to a hospital if needed. The anesthetist must ensure that sedation is deep enough to ensure proper alignment of the light source without the eye rolling back. Clinicians should be aware that patients with Down syndrome are at higher risk of anesthesia-related complications. They may also not be good candidates for corneal transplant, due to difficulty following postoperative instructions. Soeters and colleagues recently provided a tool to help clinicians decide whether such patients can be successful under local anesthesia (1).

There is still an enormous issue with access to care in the population with intellectual disabilities. In many cases, state Medicaid insurance programs still do not cover CXL, much as they once covered penetrating keratoplasty but not the less invasive DSEK and DMEK procedures. I believe that CXL will also eventually be Medicaid covered, with time and advocacy by corneal surgeons. For anxious patients, and patientswith learning disabilities alike, it may eventually be very beneficial to have an FDA-approved epi-on procedure. A less invasive procedure could help anxious patients be less fearful.

Older patients

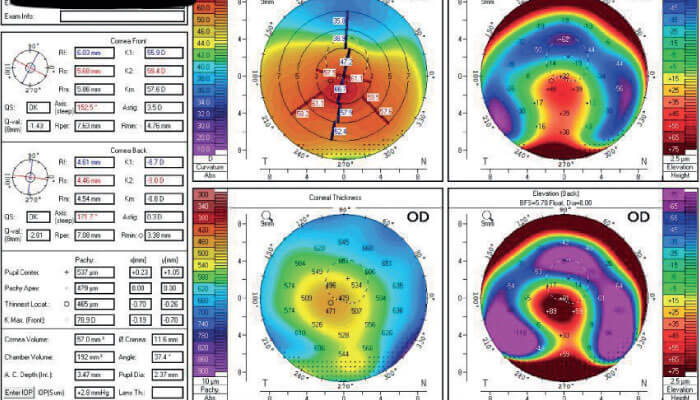

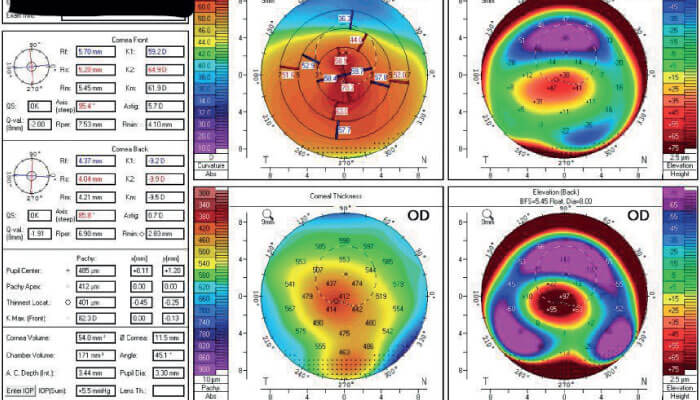

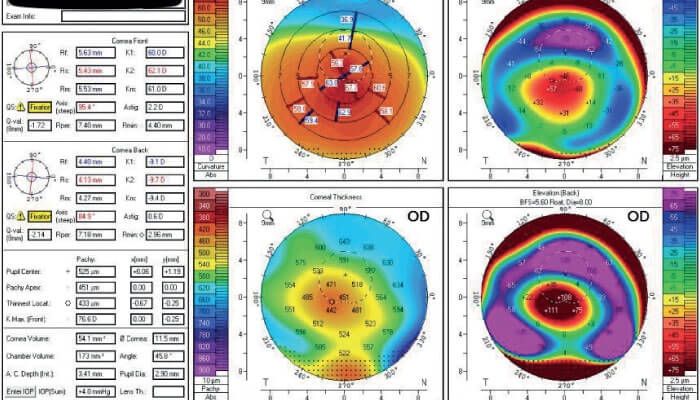

Keratoconus is a life-long disease. Although it is less well recognized, some patients can still have significant progression after age 40 (see Figure 1). It is not uncommon for a patient to notice their vision changing (beyond just presbyopia). Upon exam, I may find unusual topographic features, but also some early cataract that makes it difficult to determine the source of the vision change. But when I see them again in 6-12 months, there is clear evidence of progression. The good news is that older patients are probably progressing much more slowly than younger keratoconus patients (3), so we do have the luxury of time to confirm the diagnosis and schedule treatment.

In addition to the slowing down or halting progression, CXL often results in some corneal flattening. I find this to be particularly helpful with older patients (and essentially all patients), because it may mean they can get back into an easier form of vision correction (4), with significant cost and lifestyle benefits.

Post-refractive ectasia

I think it is still an open question whether true post-refractive ectasia actually exists. The cases we label as post-refractive ectasia may have had undiagnosed ectatic disease before the refractive surgery or there may be an inflammatory component (from excessive eye rubbing), even though ectasia is traditionally defined as a non-inflammatory condition. In any case, in patients with previous refractive surgery, clinicians should be very careful with epithelium removal along the flap edge so as not to accidentally disrupt the flap or open old incisions. Additionally, I always try to address any underlying issues that may have led to eye rubbing, such as eczema, dry eyes or allergy.

With cross-linking, we have a wonderful opportunity to potentially halt a sight-threatening disease and protect patients’ vision. With proper verbal anesthesia and appropriate precautions for unusual cases, a wide range of patients diagnosed with progressive keratoconus or post-refractive ectasia can be treated very successfully.

References

- N Soeters et al., “Performing corneal crosslinking under local anesthesia in patients with Down syndrome”, Int Ophthalmol, 38, 3, 917 (2018). PMID: 28424993.

- M Shapiro and T France, “The ocular features of Down’s syndrome”, Am J Ophthalmol, 99, 659 (1985). PMID: 3160242.

- T McMahon et al., “Longitudinal changes in corneal curvature in keratoconus”, Cornea, 25, 3, 296 (2016). PMID: 16633030.

- K Singh et al., “Alterations in contact lens fitting parameters following cross-linking in keratoconus patients of Indian ethnicity”, Int Ophthalmol, 38, 4, 1521 (2018). PMID: 28646439.