All doctors will know that there are certain cases that stay with you forever. For me, one such case was a young boy, Paul, from my own home village, where my parents still live. Something fell into the child’s eye, and he developed an infection – microbial keratitis. When his parents realized, they took him to a village clinic, where the young patient was given medication. The parents only brought the child to our specialized eye hospital when they became aware that the medicine wasn’t working. I knew immediately it was too late to save the eye – the infected cornea had practically melted away. I had to deliver the bad news to the parents, all the while knowing that the outcome would have been very different if they had come to me earlier. We had to remove the child’s eye, which is a difficult procedure in itself, all the time thinking of the impact this disfiguration would have on his education, future career, and other prospects.

I wanted to help find solutions to help stop more children and adults losing eyes to infection. After my ophthalmology residency, I started a collaboration with my professor, Matthew Burton, at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to help us understand the epidemiology of the disease, the underlying risk factors and causes, and how to prevent blindness. Under his mentorship, I completed a three-year PhD project, treating patients from south-western Uganda who come to us with microbial keratitis.

One of the things we were really interested was the patients’ journey: we were keen to know what happens between the time the person gets the first symptoms and the time they visit our eye hospital. It is important because microbial keratitis is what I call a “time disease.” If someone gets this condition, they should start effective treatment within 72 hours in order to have a good outcome. However, we found that it usually took patients two weeks or longer to see an eye care professional. By the time they did, for most of them it was too late to save their vision, or even their eyes.

We found that the majority – six out of 10 – of our patients used traditional eye medicine before coming to see us. This was not surprising, as in Uganda, traditional treatments are a widely used alternative to conventional medicine. We discovered that patients who used traditional eye care methods came to us much later, and their outcomes were much worse, compared with patients who did not use alternative methods; a much larger proportion of the first group became blind, or lost their eyes.

Traditional medicines are commonly contaminated and contain microorganisms that can damage the eye. A pre-existing eye condition, such as an injury (common in farmers or gardeners), corneal scar or local infection around the eyelids or the eye drainage system, gives microorganisms easy access to the eye. Also, conditions such as HIV or diabetes, or applying steroids to the eye, reduce the immune system’s natural ability to fight off an infection.

Traditional trouble

Ideally, we would simply like to encourage people not to use traditional eye medicine, but achieving behavioral change is extremely difficult, especially when it results from deep-rooted beliefs. In the local language, microbial keratitis is described as a “storm” – a destructive force that people believe only traditional medicine is capable of curing. Community elders and traditional healers – respected members of the community – tend to encourage this viewpoint. Using the findings of our research, we were fortunate to obtain a large Wellcome Trust funding to Matthew Burton and to me as a post-doctoral research fellow to do a series of multinational and multicenter interventions to prevent severe infections due to microbial keratitis. One of the interventions is to explore ways of influencing behavioral change in the community. We decided to work on “sensitization messages,” and have been fortunate to be working with Terry Cooper, an award-winning photojournalist, to develop audio-visual messages focusing on the experiences of patients who had used traditional medicine in eye care. We intend to record their messages and distribute them in local communities. Hearing messages from their peers is a lot more effective for people than listening to a “white coat” physician, and they begin to realize the danger and the extent of damage that traditional methods can cause.

Telling traditional healers that their ways don’t work is proving to be even more controversial, but with clear evidence and real case studies it is possible. It would not be wise to antagonize healers, so we need to find a way to bring them on board. There is a precedent to our work: Uganda has a history of HIV pandemic, and one of the ways it was combated was through health workers and healers working together. The umbrella body for traditional healers of Uganda (THETA) worked with healthcare professionals, and made changes to their practice, for instance, not using the same knife for different patients. We hope that we can emulate this important work in eye care, and that this way of getting our message across to communities will work to the benefit of our patients.

Our treatment protocol for patients with microbial keratitis

Affected patients usually experience pain and a foreign body sensation in the eye, as well as redness and excessive tear production. It is sometimes caused by an object falling into the eye or an injury. Our first step is to screen all patients for HIV and diabetes, since we found that almost 40 percent of HIV-positive patients did not know they were infected before coming to us with an ophthalmic issue. We then conduct an ocular examination using a torch and a slit lamp, and document the findings.

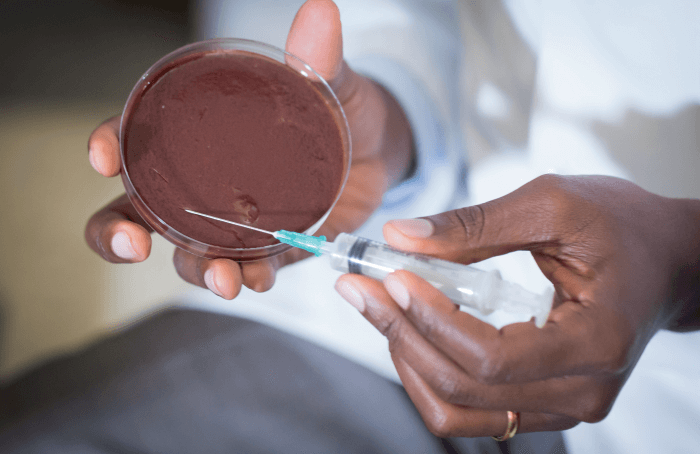

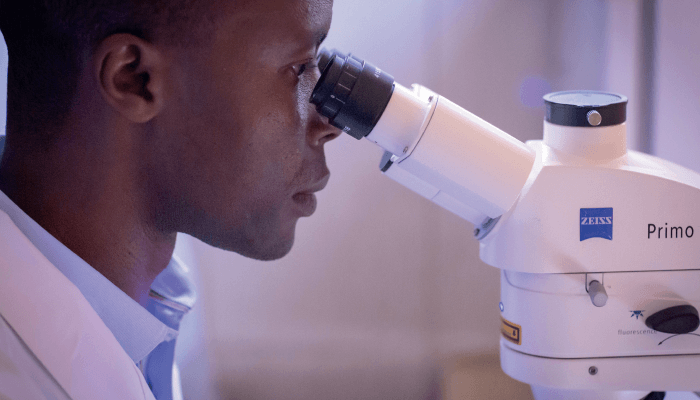

Before checking patients’ vision, we take photographs of the front of the eye to document clinical findings digitally. Following that, we apply anesthetic drops and take a sample from the cornea at the slit lamp or under an operating microscope if the patient is anxious. We use some samples for microscopy, some as culture, and some as genetic PCR material.

We are fortunate to have a laboratory microscope that helps us to quickly determine if someone has been infected by fungi or bacteria – that is critical when deciding on the initial treatment. We recently set up a state-of-the-art confocal microscope that allows us to visualize fungal hyphae directly in the corneal tissue. We send the rest of the samples to the main microbiology lab, where they are processed, and we get the results back in two to three days. By that time, the patient will have already started initial treatment. Depending on the severity of the condition, some patients can be treated at home, or if the infection is severe, they are admitted to hospital for close monitoring.

In the first week, the treatment is given hourly, day and night, until the patient responds to medication. On average, patients with fungal keratitis are treated for 8–10 weeks, and patients with bacterial keratitis require a much shorter treatment regime. If a patient does not respond to the treatment, we amend it depending on the culture and the sensitivity results we receive from the lab.

If there is a perforation, we sometimes apply glue and use a contact lens, but we mostly use a conjunctival flap, and occasionally perform an ultrasound to check if the infection has extended to the deeper layers of the eye. If the eye needs to be removed, we offer the patient counselling. We also work with a trained oculist – a technician whom we trained at Aravind Eye Hospitals as part of the funding for the PhD project able to fit artificial eyes. We discharge patients from our care after three months, following control appointments.