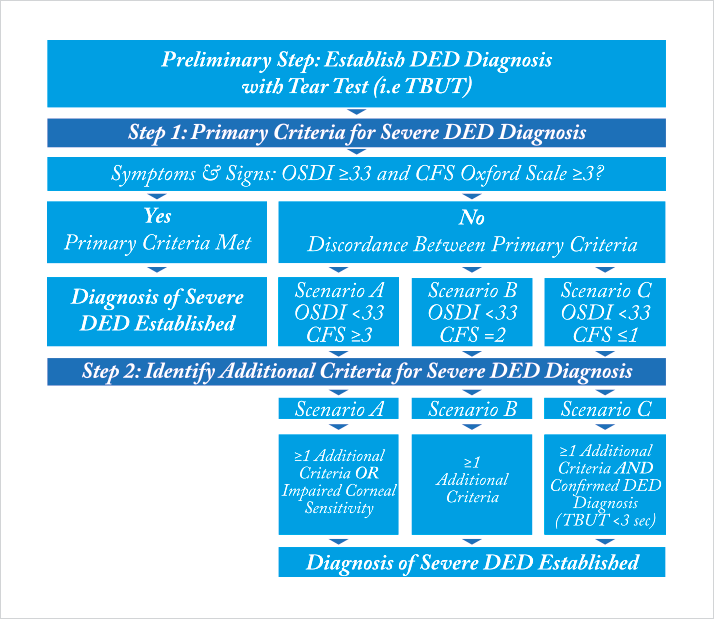

Diagnosing dry eye disease (DED) is a challenge. As we saw last month, it’s a multifactorial disease, with many disparate causes. DED has a highly variable symptom profile at different stages of the disease, and there’s often a discordance between signs and symptoms (1,2): a patient can have severe symptoms, yet show no sign of ocular surface damage, whereas others have advanced ocular surface damage, yet report no symptoms. Historically, this has been characterized by a lack of correlation between patients’ subjective irritative ocular symptoms (as determined by, for example, questionnaires) and the results of commonly performed objective tests, such as corneal fluorescein staining (CFS) and tear film break up time (TFBUT). Clearly, symptoms alone are not enough to obtain an accurate and timely diagnosis of the severity of many cases of DED – which can impact upon treatment decisions and complicate the evaluation of disease progression. This was the situation when members of the ODISSEY European Consensus Group met in September 2012, with the goal of reviewing the clinical and scientific challenges in diagnosis and management of severe DED and generating an algorithm that identifies the criteria most relevant to thepatient. This would allow for a simplified, targeted and reproducible evaluation of the ocular surface and facilitate the assessment of disease severity (3). They discussed and evaluated 14 criteria for DED severity (Box 1), eventually producing a two-step scoring algorithm for diagnosing severe DED (Figure 1), with just two criteria – a symptomatic assessment with the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire and an evaluation of ocular surface damage by CFS being sufficient as a frontline assessment of DED severity for the majority of patients. Where there was discordance between signs and symptoms, further assessments are recommended with eight “determinant” factors being listed – and these included biological markers of inflammation and apoptosis as well as osmolarity and meibomian gland disease or eyelid inflammation. Their presence, in addition to OSDI scores ≥33 or CFS score ≥3 on the Oxford scale, was accepted as diagnosis of severe DED.

Box 1. List of the markers and evaluations of disease severity, as discussed by the ODISSEY European Consensus Group.

- Aberrometry

- Blepharospasm

- Conjunctival staining

- Corneal fluorescein stainin

- Filamentary keratitis

- Impaired visual function

- Impression cytology

- In vivo corneal confocal microscopy

- Inflammatory biomarkers (e.g. HLA-DR, MMP9, cytokines)

- Meibomian gland disease or eyelid inflammation

- Refractory to standard disease treatments

- Schirmer test

- Tear film breakup-time

- Tear hyperosmolarity

It’s long been known that most patients find long questionnaires boring, so it’s important to keep the number of questions down to the absolute minimum – the OSDI questionnaire asks only twelve. However, OSDI address the symptoms’ frequency but not the intensity. DED – particularly severe DED – negatively impacts patient QoL, which is in turn, poorly associated with clinical findings (4–7). A new questionnaire, developed and validated first in Japan (and now in the UK): Dry Eye–Related Quality-of-Life Score (DEQS) successfully combines both symptoms (frequency and intensity) and QoL in just 15 questions, and was found to have good reliability, validity, specificity, and responsiveness for the assessment of DED symptom severity and their effect on QoL (8). The multifactorial nature of DED, combined with the confusing discordance between signs and symptoms will always mean that the diagnosis and staging of DED and its impact on QoL has been particularly challenging, but diagnostic algorithms, such as ODISSEY, and easy-to-use patient-reported outcomes, such as DEQS, are improving the situation, and benefitting patients with DED.

Next month

Treatment challenges and the need for European consensus Patients with severe dry eye in the EU have a problem: few effective treatment options, and little in the way of professional consensus regarding what the best course of treatment is. Lubricant eyedrops and ointments often fail to provide relief – as they do not address the underlying problem of ocular inflammation. Corticosteroid eyedrops have a potent anti-inflammatory effect… but come at a cost of common and concerning side-effects like cataract and IOP elevation. Ciclosporin eye drops should be an option – but to date, this has either meant off-label commercial products, or impractical hospital pharmacy-produced ciclosporin formulations that require refrigeration and have a short shelf-life. Patients with severe dry eye in Europe need something better than the current treatment options – so we’ll explore what could meet their requirements in next month’s issue.

References

- KK Nichols, JJ Nichols, GL Mitchell, “The lack of association between signs and symptoms in patients with dry eye disease”, Cornea, 23, 762–770 (2004). PMID: 15502475. BD Sullivan et al., “Correlations between commonly used objective signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of dry eye disease: clinical implications”, Acta Ophthalmol, 92, 161–166 (2014). PMID: 23279964. C. Baudouin et al., "Diagnosing the severity of dry eye: a clear and practical algorithm", Br J Ophthalmol., 98, 1168–1176 (2014). PMID: 24627252. S Vitale et al., “Comparison of the NEI-VFQ and OSDI questionnaires in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome–related dry eye”, Health Qual Life Outcomes., 2, 44 (2004). PMID: 15341657. M Li et al., “Assessment of vision-related quality of life in dry eye patients”, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 53, 5722–5727 (2012). PMID: 22836767. M Li et al., “Anxiety and depression in patients with dry eye syndrome”, Curr Eye Res. 36, 1–7 (2011). PMID: 21174591. KW Kim et al., “Association between depression and dry eye disease in an elderly population”, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 52, 7954–7958 (2011). PMID: 21896858. Y Sakane et al., “Development and validation of the Dry Eye-Related Quality-of-Life Score questionnaire”, JAMA Ophthalmol. 131, 1331–1338 (2013). PMID: 23949096.