Despite surgical advances, ocular inflammation after cataract surgery is a reality that, if managed ineffectively, can have a significant impact on patient comfort, recovery, and final visual outcome (1). And it doesn’t take a great deal of surgical trauma to alter the blood-aqueous barrier, resulting in protein leakage, cellular reaction, and subsequent inflammation in the anterior chamber. Diabetes, use of tamsulosin, a history of iritis, or extended phaco time are just some of the many factors that can increase the risk of inflammation following cataract surgery (2). Even low-grade inflammation, if uncontrolled, can lead to conditions such as cystoid macular edema (CME), which can ultimately cause permanent vision loss.

Topical anti-inflammatory drugs, such as corticosteroids, have been the foundation of postoperative inflammation control for half a century. With the introduction of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which are thought to complement steroids and provide additional inflammation control, it has become common for surgeons to employ both steroids and NSAIDs to control and prevent inflammation resulting from cataract surgery (3).

Advances in drug-delivery options have since expanded post-cataract inflammation management, and regimens are beginning to shift in response (See: A timeline of novel corticosteroid options). Cataract surgeons Dave Patel and Cathleen McCabe cite sustained-release drugs that remove the adherence burden from patients, and innovative delivery mechanisms that improve intraocular penetration among the options that are reshaping their post-cataract inflammation control strategy.

Years of research and development have led to several novel ophthalmic corticosteroid options that minimize or eliminate the patient’s role in reducing postoperative inflammation:

- In February 2018, Dexycu (dexamethasone intraocular suspension 9%, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals) became the first and only FDA-approved intraocular corticosteroid, administered as a single injection to treat postoperative inflammation.

- In August 2018, the FDA approved Inveltys (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 1%, Kala Pharmaceuticals), a twice-daily topical steroid for the treatment of inflammation and pain after ocular surgery.

- In November 2018, Dextenza (dexamethasone ophthalmic insert 0.4 mg, Ocular Therapeutix) was approved as an intracanalicular insert to treat postoperative ocular pain.

- In June 2019, the Dextenza insert was approved for the treatment of ocular inflammation.

- Most recently, in February 2019, Lotemax SM (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic gel 0.38%, Bausch + Lomb) was approved for the treatment of postoperative inflammation and pain after ocular surgery.

According to Patel, quelling inflammation after cataract surgery is now more important than ever because of heightened patient expectations: “Today, cataract surgery is so efficient and technology has advanced to such an extent that patients are seeking faster, easier recovery options. They have these elevated expectations, because we’ve become so good at doing cataract surgery.” As one of the most commonly performed surgeries in senior populations, Patel remarks that surgeons have become more proactive in trying to reduce recovery time – with a key objective being to aggressively treat and minimize post-surgery inflammation.

McCabe adds that the aim of inflammation control is to make sure that the ocular tissues are not surrounded by inflammatory mediators. “We want to make sure we provide a medication that, in essence, bathes tissues in a healing environment so that we can control any postoperative discomfort or light sensitivity,” she explains. However, she also emphasizes the value in thinking long term: “Inflammation can cause scarring of ocular tissues, such as posterior synechia or even peripheral anterior synechia, as well as scarring of the anterior capsule, the iris, or the cornea. If there’s enough inflammation after surgery, the capsular bag can contract; in the long term, this can lead to swelling in the retina — CME – which can affect visual function.”

For routine cataract cases, Patel says he has long implemented an anti-inflammatory regimen of topical steroids, including Pred Forte (prednisolone acetate suspension 1 percent; Allergan), Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate suspension 0.5 percent; Bausch + Lomb), or Durezol (difluprednate emulsion 0.05 percent; Novartis), used four times a day for about three weeks. However, Patel adds that in his experience, delivering the steroid within the eye itself has the best effect as it eliminates the risk of a topically applied drug not penetrating.

McCabe’s typical regimen for uncomplicated cataract surgery is similar: Durezol, or, if a patient is a known steroid responder, Lotemax, as well as Prolensa (bromfenac ophthalmic solution 0.07 percent, Bausch + Lomb). “Another way of providing a post-operative anti-inflammatory effect is to use Omidria (phenylephrine ketorolac intraocular solution 1 percent/0.3 percent, Omeros) at the time of cataract surgery,” she says. Combining Omidria with a sustained-release steroid formulation, she adds, could allow patients to avoid topical anti-inflammatories altogether.

When prescribing a week-long regimen of multiple postoperative eye drops, it’s important to consider the likelihood of patients being able to manage. “It’s crucial to have a good understanding of your patients and their dynamic outside of the office. For the most part, this is a geriatric population, so their memory might not be perfect. They may not remember to use the medication; or sometimes they have arthritis and administering the drug is challenging,” explains Patel. On top of this, it is common for patients to have comorbidities – such as diabetes or retinal membranes – that require more aggressive or longer-term steroid use. McCabe tends to employ a “belt-and-suspenders” approach for more challenging cases (for example, when she is worried about non-compliance or a predisposition to inflammation-associated complications), which relies on a layered combination of steroidal products.

Surgical factors also need to be considered in the decision and may lend themselves to a more customized approach for inflammation control. “Patients who have had a lengthy surgical process – those who require manipulation of the iris, or patients who had complications such as a posterior capsular break – will have prolonged or excessive inflammation,” explains Patel. “Similarly, patients who have had previous bouts of uveitis or inflammation tend to have a more robust inflammatory response to surgery or injury, so they require a lot more steroid treatment as well.”

Patel points out another anatomy-related obstacle when steroids are delivered topically; getting the right amount of drug in the eye. “Some patients may have corneas that do not process the steroids as expected. When this happens, we’re really not sure how much of the drug is active within the eye once it’s delivered on the surface (4).”

Ultimately, patients who are poorly adherent to their postoperative drop schedule tend to have a prolonged visual deficit because the inflammation can limit the quality of vision. Patel also highlights the additional risk of inflammation within the retina causing secondary effects, like macular edema. “The idea is really to prevent the nidus of inflammation, and using the steroids more aggressively has been shown to result in patients having better visual outcomes — and more steady outcomes — avoiding complications like retinal or macular edema.”

Both surgeons said they have generally been successful using topical steroids to counteract inflammation, and that their typical regimens tend to be effective. However, plans that rely so much on patient adherence are inherently somewhat unreliable. Thus, Patel and McCabe argue that surgeons should welcome the array of FDA-approved options now available to mitigate some of this variability.

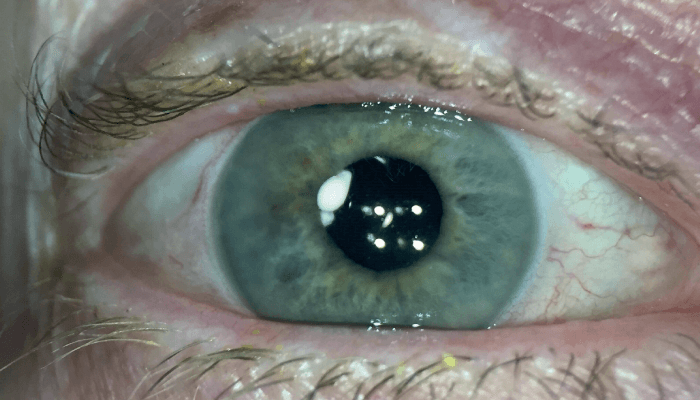

Patients with a history of inflammatory conditions or risk factors that might predispose them to a more substantial postoperative inflammatory reaction (for example, anterior uveitis, diabetic macular edema, epiretinal membrane, prior retinal surgery, or retinitis pigmentosa) may benefit from an alternative approach. McCabe has begun to favor sustained-release options, such as Dexycu (dexamethasone intraocular suspension 9%, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals), or Dextenza (dexamethasone ophthalmic insert 0.4 mg, Ocular Therapeutix). Dexycu is injected into the ciliary sulcus at the end of cataract surgery, where it delivers a bolus of dexamethasone that tapers over the first few weeks after surgery, when it dissolves completely (see Figure 1). Dextenza is inserted into the lower lid tear canaliculus at the end of cataract surgery, where it elutes dexamethasone onto the ocular surface and gradually resorbs after about 30 days (see: Tackling Drug Delivery).

Figure 1. In some cases, Dexycu may be visible at the pupillary margin in the immediate postoperative period. Image courtesy of Dave Patel.

A number of innovations in corticosteroid drug formulations have enabled improved delivery to the eye, including molecules with improved penetration and sustained-release drugs.

Better penetration

Changes to the formulation of an established ophthalmic steroid, loteprednol etabonate, aim to improve penetration into the eye and reduce dosing:

- Inveltys. Using mucus-penetrating particle (MPP) technology the company refers to as AMPPLIFY, Inveltys is able to better penetrate through ocular surface mucin barriers. According to preclinical data, it delivers 3.75 times more loteprednol etabonate to the aqueous humor compared with a traditional suspension. It is also differentiated from other topical corticosteroids by its indicated dosing schedule – twice daily, versus three or four times a day for other options (4).

- Lotemax SM. Similarly, Lotemax SM delivers loteprednol etabonate in a submicron particle size for faster drug dissolution in tears (5, 6), providing two times greater penetration to the aqueous humor compared with Lotemax Gel (7). The enhanced penetration enables less frequent dosing (three times per day), and ultimately, less reliance on patient adherence to the drop schedule.

Sustained release

Two formulations of dexamethasone are designed to be placed by surgeons — one directly into the eye, one into the lower punctum — effectively removing patients’ involvement in postoperative steroid administration:

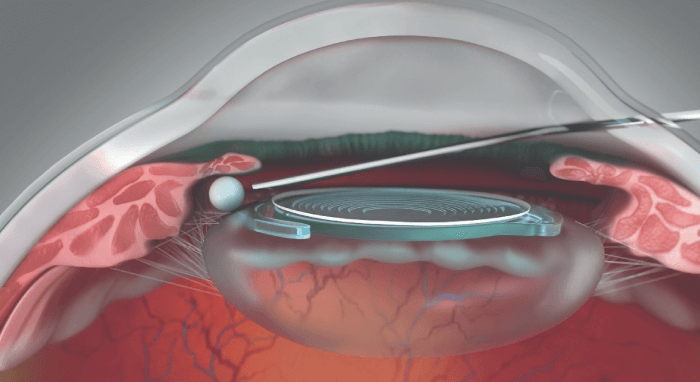

- Dexycu. Formulated using the proprietary Verisome sustained-release technology, Dexycu is a cohesive, bioerodible liquid steroid depot injected into the ciliary sulcus at the end of cataract surgery, where it delivers a tapering dose of dexamethasone for about 21 days (see Figure 2). In controlled clinical studies, Dexycu provided a significant anti-inflammatory effect that began early and was sustained throughout the postoperative period (8, 9).

- Dextenza. Another dexamethasone delivery system, Dextenza uses a resorbable hydrogel device inserted at the end of surgery into canaliculus of the lower lid, where it remains in place for about 30 days, delivering a tapered dose of medication to the ocular surface (10).

Figure 2. The bioerodible, sustained-release Dexycu is delivered behind the iris at the end of surgery. Image courtesy of EyePoint Pharmaceuticals.

“If I think there’s a higher risk of inflammation postoperatively, I will use something that’s less dependent on patient compliance. And that even includes when I think the patient might not be able to afford the drops. The idea is to insert something in the OR, so I don’t have to rely on their ability to access the drug or to put the drug in,” says McCabe. “In addition to eliminating compliance issues, putting the medication in the eye has some real advantages, such as providing constant dosing. Instead of peaks and troughs that may happen if there’s a missed dose here or there, with an implant or insert we know that it’s always there, and the dosage is tapered throughout the course.”

Patel started out using Dexycu only in high-risk eyes, but he noted that there are many other clinical scenarios in which Dexycu may be useful, including routine cases. “I’ve also utilized Dexycu in eyes that are undergoing combination cataract and glaucoma surgery, because they tend to have more reaction within the chamber, requiring more steroids, or more frequently dosed steroids,” he says. “I’ve chosen to use this intracameral formulation in the hopes that it can better control the inflammation, and resolve patients’ post-surgical care in a rapid fashion.”

“The advantage with Dextenza versus eye drops is that it may enable the patient to have a shorter duration of treatment, and patients are not required to administer it,” says Patel. “However, with Dextenza, an enzymatic process has to take place for it to penetrate into the anterior chamber of the eye, which is no different than with the topically applied drugs. My concern with Dextenza is the possible variability of effect. We’re not really sure how much of that drug is released, depending on the patient’s anatomy, so we are essentially theorizing that it’s a slow, sustained release, when in fact the concentration may be variable, depending on the eye being dry or lubricated, and how much of the implant is exposed within the tear duct.”

So what now? It is clear that cataract surgery has come a long way: from extracapsular extraction and weeks of recovery to micro incisions and spectacle independence. Now that the surgery itself is so refined, one key to giving patients the best surgical experience and outcome is minimizing postoperative inflammation. It seems counterproductive to leave this crucial part of the process literally in the hands of patients, when options with less variability now exist. Novel anti-inflammatories will hopefully drive the future of postoperative treatment regimens and help provide patients with the best visual outcomes after cataract surgery.

References

- R Lindstrom, “Reducing the Risk for Inflammation and Infection Following Cataract Surgery” (2014). Available at: https://bit.ly/36D2PhL.

- CA Murrill et al., “Postoperative care of the cataract patient”, Clinical Ocular Pharmacology, 4, 729, (2001).

- JR Wittpenn et al., “A randomized, masked comparison of topical ketorolac 0.4% plus steroid vs. steroid alone in low-risk cataract surgery patients”, Am J Ophthalmol, 146, 554, (2008). PMID: 18599019.

- K Järvinen et al., “Ocular absorption following topical delivery”, Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 16, 3 (1995).

- Kala Pharmaceuticals, Available at: https://inveltys.com.

- P Khadka et al., “Pharmaceutical particle technologies: an approach to improve drug solubility, dissolution and bioavailability”, Asian J Pharm Sci, 9, 304, (2014).

- E Phillips et al., “Viscoelastic and dissolution characterization of submicron loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic gel, 0.38%”, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 56, 1525 (2015).

- ME Cavet et al., “Ocular pharmacokinetics of submicron loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic gel 0.38% following topical administration in rabbits”, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 56, 1524 (2015).

- E Donnenfeld, E Holland, “Dexamethasone intracameral drug-delivery suspension for inflammation associated with cataract surgery: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial”, Ophthalmology, 125, 799 (2018). PMID: 29397189.

- ED Donnenfeld et al., “Safety of IBI-10090 for inflammation associated with cataract surgery: Phase 3 multicenter study”, J Catract Refract Surg, 44, 1236 (2018). PMID: 30139638.

- SL Tyson et al., “Multicenter randomized phase 3 study of a sustained-release intracanalicular dexamethasone insert for treatment of ocular inflammation and pain after cataract surgery”, J Cataract Refract Surg, 45, 204 (2019). PMID: 30367938.