Corneal collagen cross-linking slows or halts the progression of keratoconus. Ideally, patients should be treated early, before there is significant corneal damage. However, there are very good reasons to consider cross-linking instead of –or prior to – keratoplasty, even in cases with more advanced disease. Here, I’ll address some of the misconceptions I’ve seen regarding older patients and those with more advanced disease.

Myth 1: Older patients don’t progress

It is a commonly held belief that eyes with keratoconus will eventually undergo natural, age-related cross-linking and stop progressing by age 30 or 40. A corollary to this is the belief that cross-linking interventions don’t work after this point and that any adult who continues to progress beyond their third decade should undergo keratoplasty. Though it is certainly true that we see the most significant and rapid progression in younger patients, there is evidence that progression continues beyond the 30s (1). I have personally seen plenty of patients over age 50 with corneas that continue to thin and steepen – and they have benefited from corneal collagen cross-linking. I don’t believe anyone is “too old” for cross-linking if progression can be confirmed. In short, older patients do tend to progress, but often at a slower rate (2).

Myth 2: Vision can’t be improved in patients with advanced keratoconus

Many doctors believe that a patient whose vision has decreased to 20/60 is a “lost cause” who would be better served by keratoplasty. They may feel confident in their ability to achieve near-20/20 vision with a graft and believe that would be more expedient than cross-linking. There are a couple of problems with this line of thinking. First, although the primary goal of cross-linking is to slow or halt progression, we also know that the corneal flattening achieved with the procedure does have some impact on vision, with considerable individual variation (3). I have countless patients who have had dramatic visual improvement after cross-linking. Given this possibility, I would rather give patients the opportunity to see what effect the corneal flattening has on their visual function before proceeding to a transplant.

Additionally, I would rather address the visual acuity problems with cross-linking plus contact lenses than count on a perfect transplant result. As long as there is no scar in the visual axis, well-fitting scleral lenses are likely to provide very good visual acuity, even in cases of advanced keratoconus. In fact, I have seen many patients with steep cones who can only see 20/400 with glasses, but can get to 20/20 or 20/30 in a scleral lens—and I offer cross-linking to preserve this function. It’s very possible their vision won’t be any better than that with a transplant, anyway, and by cross-linking we spare them the surgical trauma and risks of infection, glaucoma, cataracts, and graft rejection. Even in cases where I think a patient will ultimately need a graft, I would almost always recommend cross-linking first. Keratoconus can recur in the graft (4), so it makes me more comfortable to know the host cornea rim has been treated and is more stable.

I am particularly bothered by a rush to transplant in very young patients. I saw a 14-year-old male with progressive keratoconus for a second opinion in 2017. His Kmax in the right eye (the worst eye) was 63.8 D (see Figure 1a), uncorrected vision was 20/100- and best-corrected acuity was 20/80. Although the visual acuity appeared to justify a keratoplasty, the cornea was crystal clear. I performed cross-linking and, by the three-month visit, his Kmax had flattened by 1.1 D, improving the uncorrected vision to 20/30-2 and best-spectacle-corrected vision to 20/30. That would have been an outstanding result from a graft, but by avoiding the transplant, he has avoided so much hassle and risk. At his four-year visit, the Kmax had decreased to 60.7, for an improvement of 3.1 D since treatment (see Figures 1b and c). His uncorrected vision was 20/30 and his best corrected vision was 20/20-.

We have to keep in mind that teens are very active and more subject to trauma than adults. They may stop using their drops and cease to return for follow-up due to lifestyle or health insurance changes. They have a high likelihood of needing one or more repeat grafts in their lifetime. I believe we must consider not just the visual acuity but the lifetime risks of cross-linking versus transplant in deciding on the optimal course of treatment for young patients with progressive keratoconus.

Myth 3: If the patient has lost vision and is contact lens intolerant, it is time for a transplant

Cross-linking often reshapes the cornea enough to make a contact lens easier to fit and more comfortable. Several papers have now reported marked improvements in subjective and objective contact lens fitting and longer duration of tolerable wear after cross-linking, including among previously contact lens intolerant patients (5, 6). In some cases, this may give the patient the ability to shift to an easier and less expensive form of vision correction (such as glasses or soft contact lenses). But even in severe cases, where patients have lost best-corrected acuity, I find that almost everyone can be fit with advanced contemporary scleral lenses after cross-linking. It is key to work with an expert specialty lens practitioner. Again, my preference would always be to cross-link first and try the contact lens route to avoid a graft.

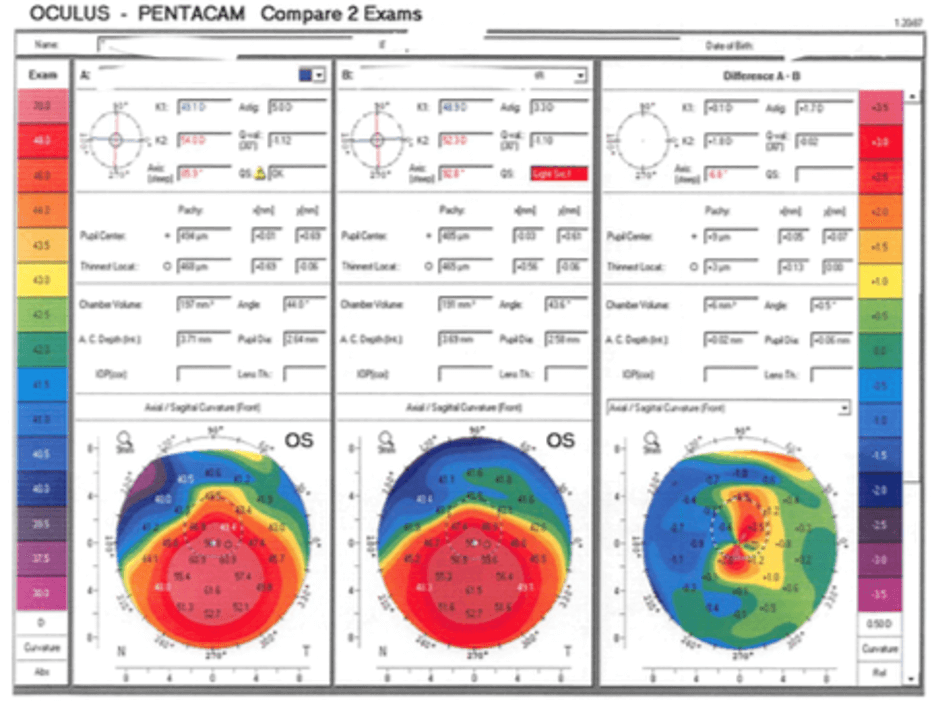

Myth 4: Increasing Kmax after cross-linking is always indicative of progression

In rare cases, patients can continue to progress after cross-linking, especially if the patient reached an advanced stage at a young age. Keratoconus patients should be followed closely after treatment for this reason. However, it is also important to know that Kmax is not the only parameter one should monitor. As the cornea undergoes surface reconfiguration after cross-linking, steep areas of the cornea flatten but it is also possible for some flat areas to steepen before stabilizing. I like to look at the difference map, which subtracts the current topography from the original, to get a better understanding of how the entire cornea has changed with treatment.

In another teenage progressive keratoconus patient I treated, the Pentacam difference map (see Figure 2) confirms that the treatment was a success. Even though this patient’s Kmax appeared to “progress” from 65.3 D preop to 67.6 D by 15 months after cross-linking, his vision improved from 20/40 to 20/25. When I’m uncertain whether I’m seeing progression, it helps to remember that we are treating a patient and not a Kmax value. If the patient’s vision and quality of life is better, the Kmax may be less important, provided the keratoconus has truly stabilized.

We have also seen some innovative algorithms that help in monitoring progression of keratoconus. The Belin-Ambrosio ABCD classification system has now been integrated into the Pentacam (but can be used with other devices) to determine when there is change beyond just measurement noise. It creates a composite score of four different parameters: Anterior (A) and posterior or back (B) radius of curvature (taken from a 3.0 mm optical zone centered on the thinnest point); minimum corneal (C) thickness; and best spectacle-corrected distance (D) acuity (7). While the ABCD classification system hasn’t been specifically validated in eyes that have already been cross-linked, it has great potential to help us with decision making at all stages of the disease.

Fortunately, more patients are being treated early in the course of their disease now that cross-linking is more widely covered by insurance and more widely available around the world. However, we will continue to see advanced keratoconus patients in our practices, and I believe that most of these patients – provided they do not have central scarring – would benefit from cross-linking before considering a transplant, regardless of their age, visual acuity, or contact lens tolerance.

References

- A Gokul et al., “The natural history of corneal topographic progression of keratoconus after age 30 years in non-contact lens wearers,” Br J Ophthalmol, 101, 839 (2017). PMID: 27729309.

- TT McMahon et al., “Longitudinal changes in corneal curvature in keratoconus,” Cornea, 25, 296 (2006). PMID: 16633030.

- PS Hersh et al., “United States multicenter clinical trial of corneal collagen crosslinking for keratoconus treatment,” Ophthalmology, 124, 1475 (2017). PMID: 28655538.

- J Alvarez de Toledo J et al., “Long-term progression of astigmatism after penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus: evidence of late recurrence,” Cornea, 22, 317 (2003). PMID: 12792474.

- K Singh et al., “Alterations in contact lens fitting parameters following cross-linking in keratoconus patients of Indian ethnicity,” Int Ophthalmol, 38, 1521 (2018). PMID: 28646439.

- M Ünlü et al., “Effect of corneal cross-linking on contact lens tolerance in keratoconus,” Clin Exp Optom, 100, 369 (2017). PMID: 27654998.

- MW Belin et al., “Determining progression in ectatic corneal disease,” Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila), 9, 541 (2020). PMID: 33323708.