Occasionally, we see a patient whose case is so unusual that it is worth describing in more detail…

Six years ago, a 37-year-old man came to our clinic at the Department of Ophthalmology of the Universitaetsklinikum Giessen in Germany, complaining about decreased vision in both eyes. He had been diagnosed with intraocular optic neuritis and anterior uveitis due to co-infection with Treponema pallidum and HIV. The patient was diagnosed with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus 30 years ago.

His best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at that time was 20/200 in his right eye and hand motions in his left eye. He was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (Rocephin) and prednisone (Decortin), in addition to topical application of prednisolone eye drops six times a day. After two days he was transferred to the Department of Infectious Diseases for further diagnostics, showing a vision improvement at discharge.

Glaucoma diagnosis

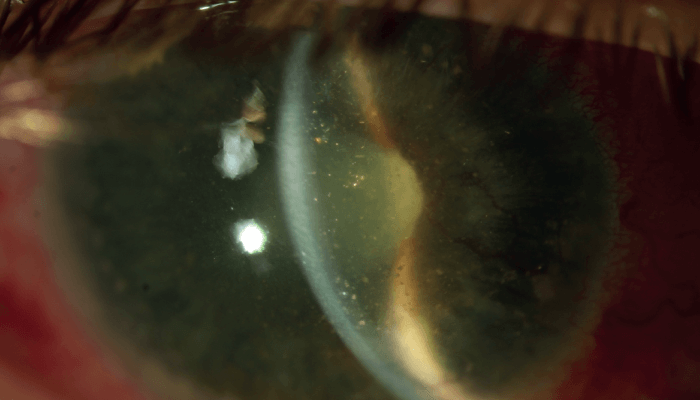

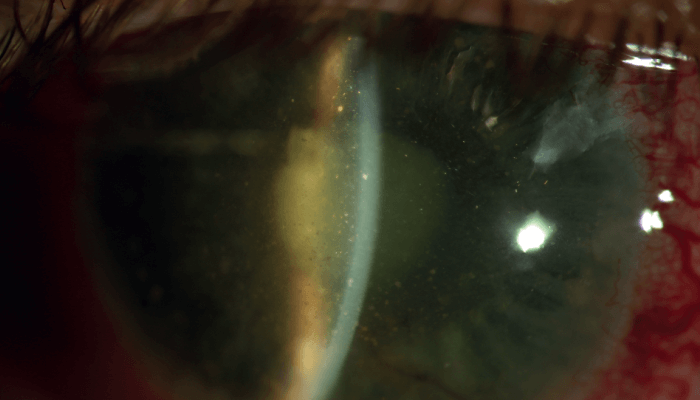

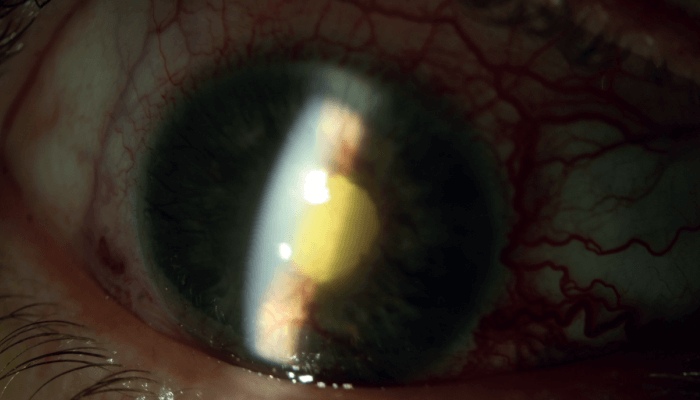

Four years later, the patient visited our department again, after suffering pain in his blind right eye for two months. His BCVA was no light perception in the right eye and 20/80 in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination of the right eye revealed conjunctival hyperemia, corneal endothelial precipitates, fibrin in a funnel-shaped anterior chamber (iris bombé), a mid-sized pupil, nonreactive to light, and a mature cataract (see Figure 1, top of the page). IOP with Goldmann applanation tonometry measured at 42 mmHg, and B-scan ultrasonography showed complete retinal detachment (see Figure 2).

At that point, the patient was diagnosed with secondary neovascular glaucoma (NVG). He had laser peripheral iridotomy (PI) (30 exposures, at 3 o’clock and 1 o’clock positions, 1.2 mJ, burst mode 1) to correct iris bombé, with IOP-lowering agents timolol, dorzolamide and brimonidine. Within one week, the pain in his right eye was markedly resolved, and IOP was under control.

The patient failed to keep the scheduled clinic appointments and revisited our clinic only five months later, showing an IOP of 48 mmHg in his right eye, corneal edema and severe iris rubeosis. The IOP in his left eye was recorded as 20 mmHg.

As the patient rejected the recommended surgical options (pars plana vitrectomy with cataract surgery or cyclophotocoagulation), we decided to administer atropine 0.5% twice a day, dexamethasone 1% twice a day, and IOP-lowering agents timolol, dorzolamide and brimonidine. Unfortunately, the patient also refused any further diagnostic procedures.

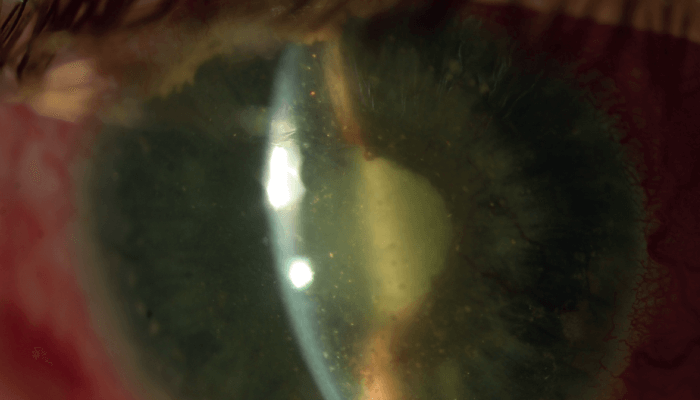

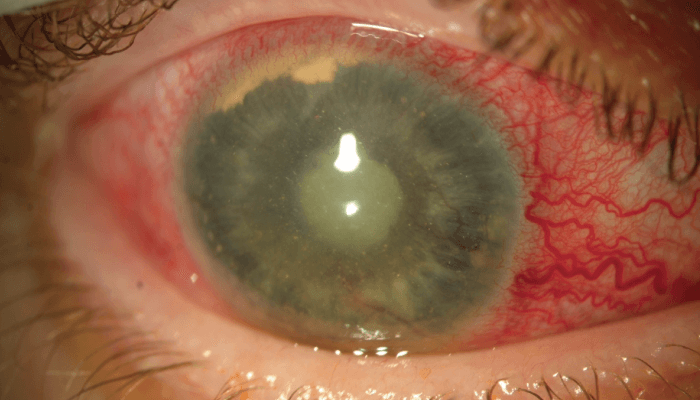

Three months later the eye examination showed that the IOP in the right eye was 18 mmHg, with mild rubeosis and cholesterol crystals floating in the anterior chamber, as well as formation and accumulation of fibrin supratemporal, causing peripheral angle closure (see Figure 3) which partially regressed in the following months (see Figure 4). IOP in the left eye was 16 mmHg. Again, the patient refused all discussion regarding surgical treatment, so we have kept him under topical IOP lowering eye drops along with atropine 0.5% twice a day, until today.

A degenerative condition

Synchysis scintillans or cholesterosis bulbi is a degenerative process defined by the deposition of cholesterol crystals in the vitreous body, subretinal space, and rarely in the anterior chamber (1, 2, 3). The underlying conditions leading to this uncommon phenomenon can be eye trauma, vitreous hemorrhage, intraocular inflammation, hyphema, secondary NVG or chronic retinal detachment, and more rarely advanced Coats’ disease, uveitis, neoplastic conditions or vascular disorders (1, 4, 5, 6). Many of these cases have been treated with enucleation due to non-manageable pain, and to prevent the development of sympathetic ophthalmia in the other eye.

Anterior chamber cholesterol accumulates in irregularly-shaped polychromatic crystals, larger in size than cells, which either float freely or are engulfed within foreign body granulomatous inflammation, macrophages or fibrous tissue (8). Sometimes they sediment to the inferior region, resembling pseudohypopyon when eye movement is limited (4, 9). Anterior chamber cholesterol is believed to be the breakdown product of intraocular blood or blood components (5, 8).

Ralph C. Eagle Jr. and Myron Yanoff reported such cases as a result of trauma or intraocular surgery, with an average interval between the trauma and the development of iridescent crystals of approximately 13 years. Elevated IOP and severely impaired visual acuity are often noted in such damaged eyes (5). Christopher Kennedy described three cases in which cholesterol appears to be the result of diffusion from the vitreous or from subretinal fluid through retinal breaks of a long-standing RD or, in the same sense, the result of an exudative RD due to Coats’ disease (10). It can also derive primarily from the anterior chamber in case of hyphema or result from phacolysis (10, 11). It is also suggested that the entry of cholesterol in the anterior chamber or the vitreous could be predisposed by the existence of aphakia or lens subluxation or by pathological changes of the blood-aqueous barrier (5, 12).

Surgical treatments

Jongseok Park reported a case similar to ours, with secondary glaucoma and elevated IOP, treated with pars plana vitrectomy and intravitreal bevacizumab, suggesting that this treatment may be an alternative to enucleation (7, 13).

We cannot exclude hyphema, either traumatic or spontaneous, as an associate cause of synchysis scintillans in our case, given that the condition could not be discovered when frank hemorrhage was no longer present and follow-up was very sparse, with long intervals in between. In our case, the intracameral injection of bevacizumab was sufficient to start regression of the neovascularization of the iris and angle, and subsequently critical for controlling the elevated IOP.

We suppose that the remission was sustained with atropine 0.5% and dexamethasone 1% eye drops, which reduced ocular congestion and inflammation in NVG. The removal of the mature cataract and the cholesterol crystals, and treating retinal detachment through pars plana vitrectomy and applying photocoagulation could possibly further help with managing the IOP.

References

- M Yanoff, J Duker, Ophthalmology, 3rd edition. Elsevier Saunders: 2014.

- J Kanski, B Bowling, Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology: A systematic approach, 8th edition. Saunders: 2015.

- ML Bastion et al., “Brilliant crystallisation in the anterior chamber and subretinal space following adjunctive intravitreal ranibizumab for diabetic vitrectomy”, BMJ Case Rep (2012). PMID: 23093508.

- A Banc, C Stan, “Anterior chamber synchysis schintillans: a case report”, Rom J Ophthalmol, 59, 164 (2015). PMID: 26978885.

- RC Eagle Jr, M Yanoff, “Cholesterolosis of the anterior chamber”, Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol, 193, 121 (1975). PMID: 1078954.

- AK Patel et al., “Picture of the month: anterior chamber cholesterolosis in Coats disease”, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 165, 1131 (2011). PMID: 22147780.

- M Eibschitz-Tsimhoni et al., “Coats’ syndrome as a cause of secondary open angle glaucoma”, Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging, 34, 312 (2003). PMID: 12875462.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology, “Basic and clinical Science Course: Section 12, Retina & Vitreous” (2018).

- J Mielke J et al., “Pseudohypopyon of cholesterol crystals occurring 16 years after retinal detachment in x-linked retinoschisis”, Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 218, 741 (2001). PMID: 11731903.

- CJ Kennedy, “The pathogenesis of polychromatic cholesterol crystals in the anterior chamber”, Aust N Z J Ophthalmol, 24, 267 (1996). PMID: 8913131.

- OA Ogun, SA Adegbehingbe, “Iridescent anterior chamber crystals following minor ocular trauma”, Oman J Ophthalmol, 2, 91 (2009). PMID: 20671838.

- JS Andrews et al., “Cholesterosis bulbi. Case report with modern chemical identification of the ubiquitous crystals”, Br J Ophthalmol, 57, 838 (1973). PMID: 4785249.

- J Park et al., “A case of cholesterosis bulbi with secondary glaucoma treated by vitrectomy and intravitreal bevacizumab”, Korean J Ophthalmol, 25, 362 (2011). PMID: 21976948.