Even before the pandemic threw a curveball, wellness of physicians was becoming an increasingly prominent subject. “Wellness” – unsurprisingly – is a multifactorial issue, with loss of physician autonomy, bureaucratic snafus, loss of the doctor-patient relationship, and trivialization of medical expertise gained over time, being a snapshot of examples. Many of these forces culminate in physicians working longer hours and having an increased throughput of patients – resulting in both mental and physical fatigue. The latter is closely intertwined with the ergonomics of the workplace and its impact on the physician’s body.

As Vince Lombardi (legendary American football coach) once stated, “fatigue makes cowards of us all.” Translating that adage to the practice of ophthalmology: a tired physician, or one in chronic pain, will perceive their own function as unsatisfactory, and this will likely lead to underperformance.

Evidence shows that ophthalmologists are over twice as likely to have neck pain, two and a half times more likely to suffer hand or wrist pain, and three times more likely to experience back pain than family medicine practitioners (1). These musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are linked to age, hours of work, numbers of procedures performed, and being female – and, shockingly, they are responsible for premature retirement in 15 percent of ophthalmologists (2).

Whodunnit?

First of all, we must ask, “Where do these problems begin?” Consider the workplace of the office and the operating theater and how physicians position their bodies – factoring in the elements of time and repetition. Slit lamps often require that the examiner pull their head forward, inducing neck hyperextension or increased lordosis. You can see in Figure 1 that the patient (on the left) has her head erect, whereas the examiner (on the right) has craned her neck in order to see through the oculars – a posture that may lead to permanent structural damage to the neck.

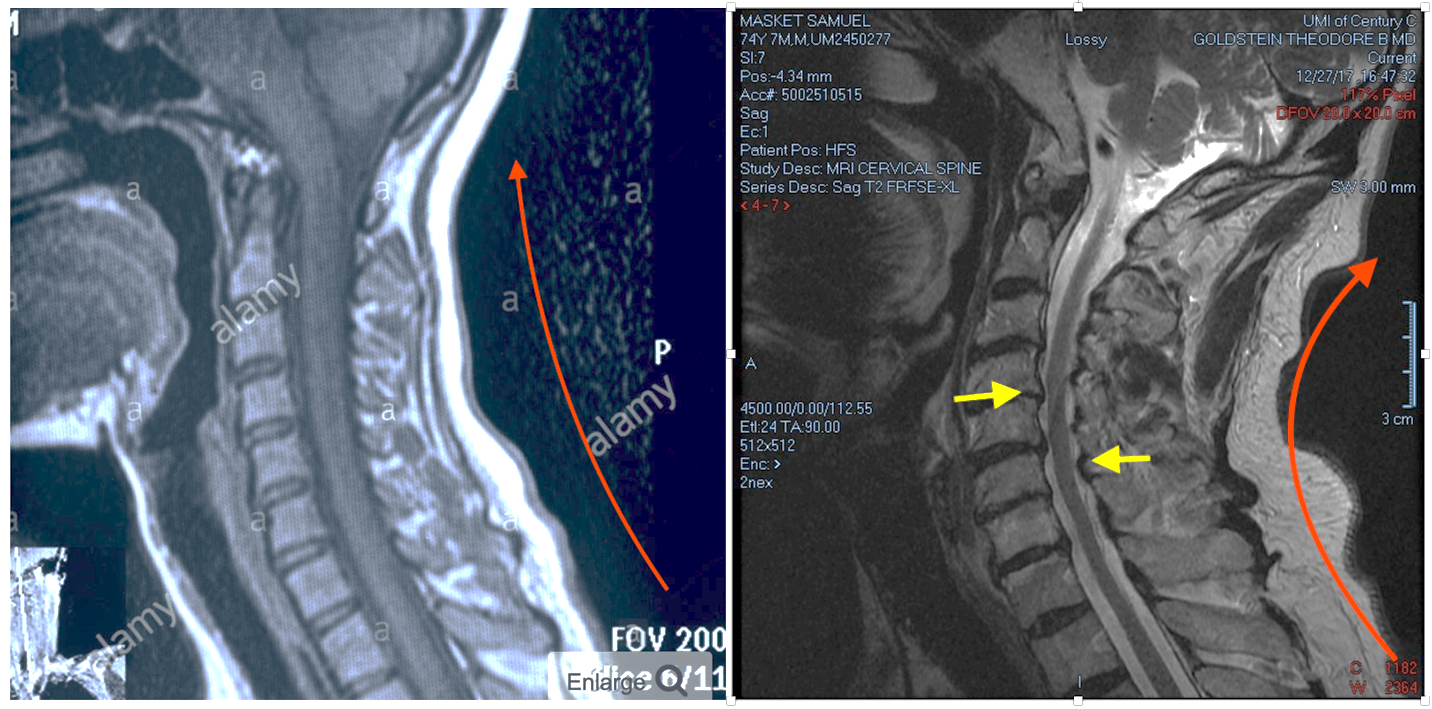

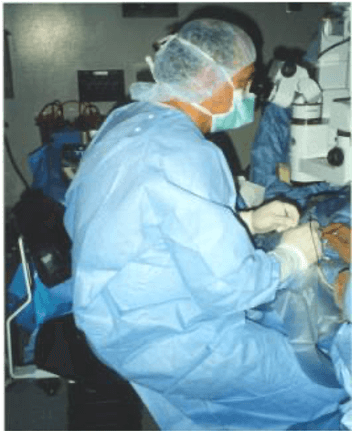

A good example of this is my own neck! You can see the structural changes that have occurred after a long ophthalmology career in my now 74-year-old neck compared with a healthy young adult neck MRI on the left to that of mine (see Figure 2) – particularly the increased lordotic curve (red line) and the stenotic cervical canal (yellow arrows). I have no doubt that the changes in my neck are related to an absence of good ergonomic design and posture planning during my career. Moreover, indirect ophthalmoscopy with a patient whose neck is in an erect position forces the examiner into contortions that will undoubtedly induce fatigue and, later on, structural damage to the back (see Figure 3). During my training program, indirect ophthalmoscope exams were carried out with the patient supine on an examination table, inducing far less stress; however, in daily clinical practice this is impractical.

Another culprit is the operating theater, where the surgical microscope causes surgeons to conform to a standardized set up – making it difficult to properly perform surgery and assure patient comfort for best results (see Figure 4). It is uplifting to recognize that a newer approach to surgery incorporates a “heads up” remote view for the surgeon, reducing neck stress (see Figure 5).

A final set of burdens to an ophthalmologist’s physical wellness are computer monitors and keyboards, which can both add significant stress to necks and wrists when not arranged with occupational health in mind.

Prevention – better than cure

Physical changes that occur in senior surgeons are likely chronic – and remediation is therefore challenging if not impossible. So a major concern to me is that trainees and young practitioners appear to be largely unaware of the looming problems; after all, it is their age group that has the greatest chance of preventing MSDs. It is sobering to learn that many corporations evaluate and advise on the ergonomic set up for new office staff members – unfortunately, ophthalmology residents and fellows get no such investigation and support in their training programs. Adding insult to injury, a recent review of the literature found 41 articles related to ophthalmic operating theater ergonomics, but only nine referenced trainees (3). Early career intervention is key to remove the issue and prevent problems later in one’s career – requiring the cooperation and involvement of national and supernational organizations.

Equally important, we need coordination among equipment designers, ergonomic experts, and physical therapists to establish a plan for prevention and treatment of MSDs among ophthalmologists. Akin to professional athletes, ophthalmologists cannot compete without their own good health. With a comprehensive approach, we can improve the longevity and productivity of all eye surgeons’ careers.

References

- AS Kitzmann et al., “A survey study of musculoskeletal disorders among eye care physicians compared with family medicine physicians,” Ophthalmology, 119, 213 (2012). PMID: 21925736.

- KC Dhimitri et al., “Symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders in ophthalmologists,” Am J Ophthalmol, 139, 179 (2005). PMID: 15652844.

- D Betsch et al., “Ergonomics in the operating room: it doesn’t hurt to think about it, but it may hurt not to!” Can J Ophthalmol, 55, 17 (2020). PMID: 32448408.