The Syrian civil war officially began on March 15, 2011. Since then, hundreds of thousands of people have been killed in the brutal conflict and more have fled to neighboring countries. Now in its 10th year, the Syrian refugee crisis is the largest displacement of the modern age. Around 5.6 million Syrians are refugees, and another 6.2 million are displaced within Syria. At least half of those affected are children (1).

Today, Syrian refugees account for over 10 percent of Jordan’s population, placing immense pressure on the country’s already overstretched medical system during one of the most difficult economic periods in its history. Although most refugees live in host communities, others find themselves in Zaatari, the world’s largest Syrian refugee camp outside of Syria. Zaatari opened in 2012 less than 10 miles from the Syrian border and has since become Jordan’s fourth-largest city (albeit unofficial).

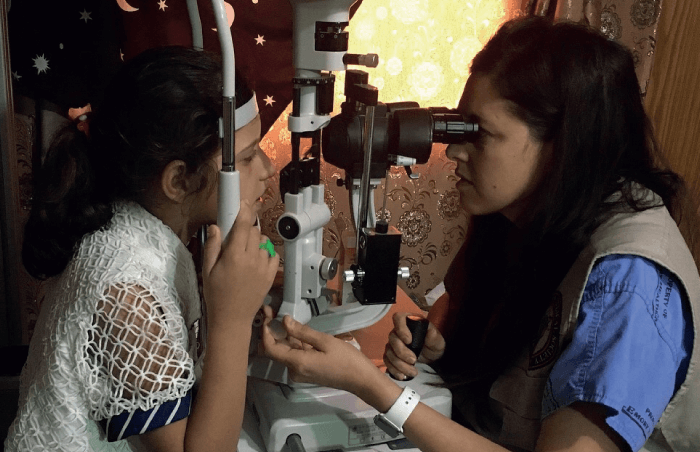

With few ophthalmologists on site, refugees rely on medical interventions provided by NGOs and volunteers, like myself, for eyecare. In 2017, anterior segment and cornea specialist, Soroosh Behshad, my colleague and cataract surgeon at the Emory Eye Center, took part in a surgical mission with the Syrian American Medical Society with the goal to treat as many people as possible. He worked his way through the adult population – but noticed a large number of children with eye problems and no one to treat them. When he returned, he asked if I would be interested in helping. Six months later, I found myself in Zaatari.

Life in the camp

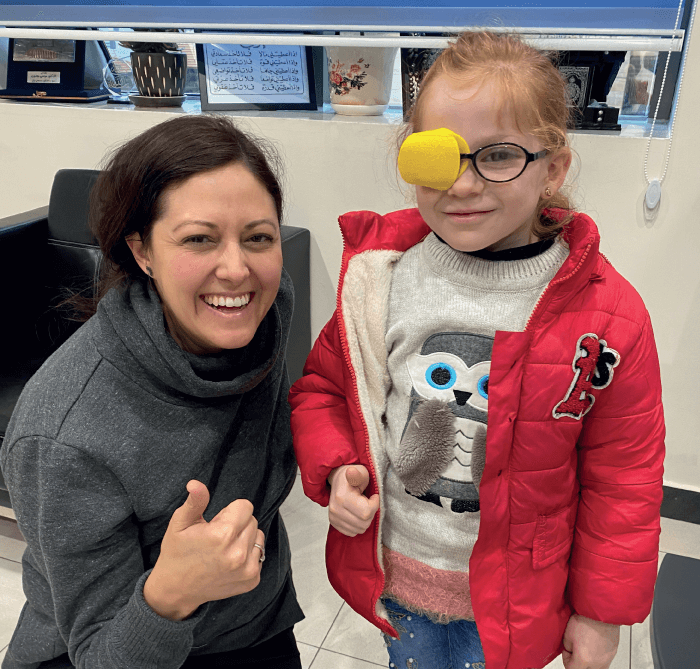

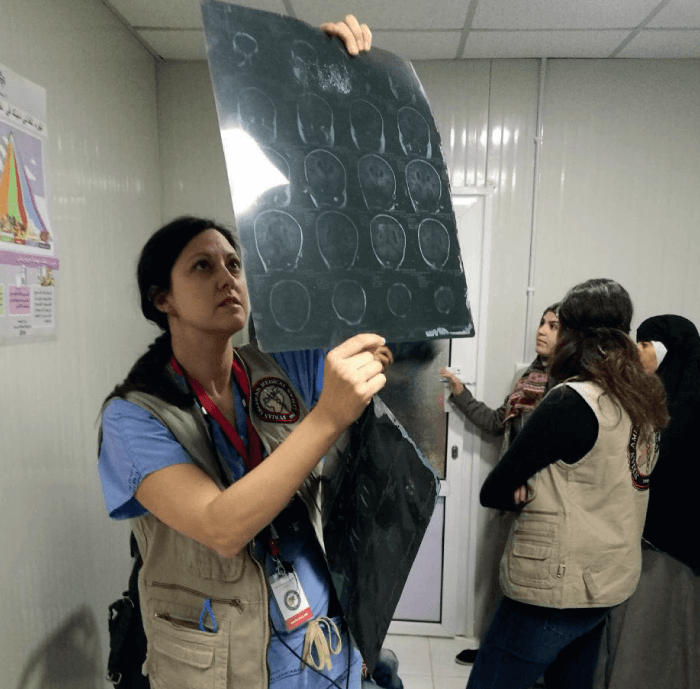

Our work was split with two different focuses: screening children and surgical intervention. Upon arriving to Zaatari on my first trip, I did not know what to expect. So, my personal goal was to screen as many children (from birth to 18) as possible over a seven-day period. I knew I would need the help of technology in order to be efficient. With the help of trained volunteers, we combined two technologies, Plus Optics and Gocheck Kids (photo screeners that help identify risk factors for amblyopia) and PEEK (a free app designed by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine that combines smartphone-based vision tests, eye health service analytics, and RAAB eye health surveys). I worked alongside Soroosh Behshad and retina specialist Aref Rifai from the Retina Center of Pensacola in Florida, US, who provided injections and photocoagulation for untreated diabetic patients. Over the course of the week, we gave out hundreds of pairs of glasses and identified countless candidates for surgery. Surgery presented its own challenges because many of the patients were not allowed to leave the camp without permission from the government, so it required a formal paperwork process to allow a patients a day’s leave and access to the hospital with an operating room. Some of our patients had not been outside the camp in seven years; others had only ever lived within its walls.

In addition, we worked with local medical students and residents to provide education and exposure to ophthalmology. In the past, we tried to find Jordanian ophthalmologists willing to perform the surgeries for free, but this was difficult as Jordan’s medical system was already under extreme stress. For a time, the government offered discounted surgeries to refugees, but this did not last long. Currently, most surgeries are paid for by the patient. By offering our services to the local population as well as to refugees, we increased access to care for poor Jordanians – and earned the government’s favor. Today, around 30 percent of our patients are Jordanian.

Ophthalmology in Jordan

We are working to create stronger relationships with the Jordanian Ophthalmology Society and various NGOs who also work in Jordan. Although Jordanians generally have a very advanced medical system, there is a shortage of subspecialists. For example, Amman, the capital, has eight glaucoma specialists for a population of more than four million. The dearth of subspecialists is partly because ophthalmologists in Jordan are required to travel for fellowships, often to Europe or the USA. Our goal is to help eliminate the need for travel, and provide local physicians with the face-to-face subspecialty training by bringing experts in the field to Amman. There are many volunteers interested in training Jordanian ophthalmologists in subspecialty care, so we hope to bring this idea to fruition soon. We hope it will not only help the refugee population, but local Jordanians as well.

Our ultimate goal is to create a permanent, self-sufficient clinic in the camp that can continue screenings by the local Zaatari camp residents. Since January 2018, we have created partnerships with various organizations, including the incredible Two Billion Eyes – an organization that brings all the equipment needed to build an optical lab and provides training to grind lenses and make glasses. Only by creating sustainable programs that can function for as long as they are needed can we have long-term change. Orbis has also been a big help in the search for funding. We have a guaranteed amount for the next two years – but, because it does not cover the number of surgical interventions the camp needs, we are applying for funding from a number of other sources.

Boots on the ground

When we travel to the Zaatari camp, we partner with the Arab Medical Relief Clinic, one of the few spaces within the camp that has ophthalmology equipment. We are also joined by a local ophthalmologist Ala’ Shalabi who visits Zaatari for half a day every two weeks to deliver eye care to many refugees. Aside from NGOs that come and go, he is the sole provider of eye care in the camp – and he works for free.

Numbers fluctuate, but there are roughly 79,000 people living in Zaatari (2). To properly serve a population of that size, we need a team of dedicated ophthalmologists, each offering subspecialty care: glaucoma, retina, oculoplastics, and pediatrics. However, that’s not feasible at this point. A more realistic goal is to have a single ophthalmologist and a few vision screeners on site every week. Behshad, Rifai and I have been trying to create a system whereby subspecialists provide surgeries to anyone who needs them via NGOs. At this stage, it is more achievable to arrange surgical trips with a volunteer every two months (followed by postoperative follow-up care) than to outsource our care – but we are getting closer to achieving our goal. Every six months, we meet with our partners on the ground, and we are finally close to hiring a full-time program coordinator and a physician, which is promising.

Prevention is better than cure

Like most volunteers, I have a full-time job in addition to my work at Zaatari. We have all dedicated a significant amount of our personal time to building this program, but it is a slow process. We haven’t received any substantial equipment donations for the clinic – so far, the only items we received from industry partners are lenses – so we rely heavily on grants. Fortunately, the medical community’s interest in refugees has increased over the last few years. As a collective, we are realizing how problematic it is that large swathes of the population have no access to medical care. Our focus is beginning to shift from acute care to preventative care. Prevention is especially important for children as their vision is in a fundamental developmental stage. A child with severe refractive error, who never receives glasses, can become legally blind for the rest of their life – but, if we intervene at a young age, they can have a normal, productive life.

We recently performed an IRB-approved vision screening study looking at 100 patients within Zaatari camp and found very high failure rates in comparison to the general population. A lot of groups work exclusively with adult cataracts, but we have identified a real need in children, too. Bringing attention to the pediatric population is a key part of our work. We are working to create a vision screening program, run by ophthalmologists, at the approximately 25 schools within the camp. We hope to create a model that we can apply to other populations in crises around the world.

The right place, the right time

People ask me why I chose this cause. I have always been interested in global ophthalmology and I’m fortunate to work at Emory Eye Center, which has one of the few training programs in the USA with a dedicated global ophthalmology initiative. The program director in 2015 was Danny Haddad, now a director at Orbis. Danny acted as my mentor, showing me how I could help on a global level. It was around this time that I became more aware of the refugee crisis. I remember sitting on my sofa, watching the news, knowing I had everything and these people had nothing. I thought, “What can I do to make an impact?” When Soroosh Behshad asked me to help, it honestly felt like my calling.

I only truly understood the scale of the problem once I got involved. Each trip, I made a list of everyone who needed surgery next time. I told them, “I will see you in six months,” and I stayed true to my word. I have been treating patients for years at six-month intervals despite living halfway around the world, and I look forward to treating them for many years to come.

Over the last few months life has changed a lot for all of us, and especially for refugees. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in regulations preventing doctors from traveling, and limiting access to the refugee camp.

Jordan has handled the pandemic very well and had very few cases. Within the country there were very strict lockdown guidelines forbidding residents to leave their home, even for essentials, during a period of time. Children began homeschooling, and for those living in the refugee camp this was through television programming, but the camp only has a limited supply of electricity per day. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the residents of Zaatari were under lockdown, not allowed to leave their shelters within the camp during the height of the pandemic. Shops were closed and people were instructed to shelter in place, except for emergencies. There have been a few reported cases of COVID-19 among refugees outside the camp.

There is much concern for preventive medicine during this time and, unfortunately, this is the first time in four years we’ve missed a trip to see our patients in Zaatari. I look forward to the lifting of regulations and getting back to helping refugee children through building a vision screening program for the children of Zaatari.

References

- World Vision, “Syrian refugee crisis: Facts, FAQs, and how to help” (2020). Available at: https://bit.ly/31ThXYN.

- World Food Program USA, “10 Facts about the Syrian refugee crisis in Jordan” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/31XR8CA.