- The Royal College of Ophthalmologists reports that 75 percent of UK eye clinics are struggling to provide the service required by their local population

- Ophthalmic training needs to meet increased demand, and reflect shifts in technology and patient demographics

- Educators need to prepare the workforce for uncertainty that comes with AI – while also instil within them the flexibility required to harness technological innovation

- Continual assessment of our curricula is essential. And by letting educationalists drive how technology is used in the education setting, rather than the other way around, we can – and will – meet today’s healthcare needs.

We are extremely fortunate to live in a time where there is so much information and research available to address ophthalmic health challenges – both now and in the future. However, with all this information comes pressure to continuously re-evaluate what we do and why. We, in education, must ensure that outdated education training does not slow the needs of patients or breakthroughs in research. Various transformations are impacting our lives, including demographic change and globalization – and these drivers are being accelerated by big data, genomics and artificial intelligence. As educators, we have a duty to be more than just responders; we need to reshape our approach to ophthalmic education to ensure we do not leave our students, staff and patients behind.

The challenge

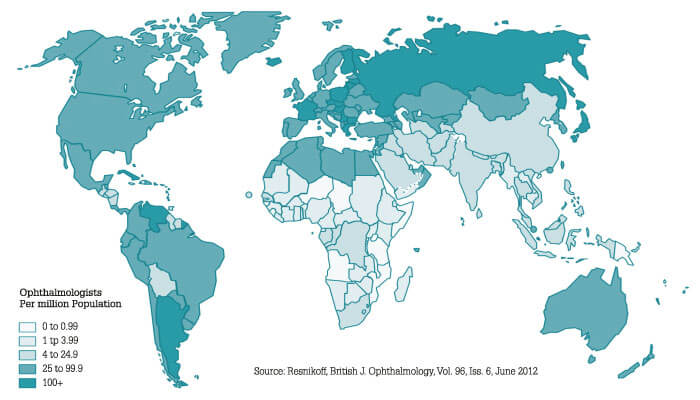

In 2010, the International Council of Ophthalmology surveyed 213 global ophthalmic societies and found 204,909 ophthalmologists practicing across 193 countries, with a significant shortfall in developing countries. Despite the number of practitioners increasing in developed countries, the population of over-60s was growing at twice the rate of ophthalmologists going into practice (1). This trend is not unique to Western countries – people are living longer all over the world. Demographic shifts mean aging populations with longer life expectancies and more comorbidities (2) will become a challenge for clinicians everywhere. In 2016, the Royal College of Ophthalmologists reported that 75 percent of hospital eye clinics in the UK are struggling to provide the service required by their local population, 50 percent of the units have unfilled consultant roles and over 90 percent are undertaking waiting list initiatives for ophthalmic surgery and clinics (3). Another study by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists forecast that demand for cataract treatment in the next 10 years is set to increase by 25 percent, while demand for medical retina and glaucoma services are expected to increase by 30 percent and 22 percent, respectively. The UK alone needs at least 326 more ophthalmologists to meet demand. Problematically, almost a quarter of ophthalmologists are over the age of 55 and so approaching retirement (4). We also see disparities of demand worldwide due to the rapid trend towards urbanization. Already, 4.2 billion of the world’s 7.5 billion people live in urban areas – a figure that will grow to 68 percent by 2050, according to the UN (5). This phenomenon causes services to be biased toward cities, leaving large regions with poor or non-existent ophthalmic services. Also, with this move comes shifts in socio-economic power and disparities in education. These phenomena are creating particular increases in secondary causes of eye disease, including diabetes and hypertension.

Rising healthcare costs are the subject of widespread concern, particularly for specialties such as vision and eye health. There is not an election in the world today where candidates fail to speak on health care access and cost containment. Economists refer to this phenomenon as the “cost disease.” They explain that the disproportionate rise in health care expenses is correlated to the fact that, while other sectors of the economy have adapted to labor savings and substitution through mechanization, health care has not (6). However, with rising demand and diminishing budgets, governments can no longer sustain a high level of health and ophthalmic care, which, in turn, puts hospital executives and clinical professionals under increasing pressure to do more with less.

If we look to other professional groups, such as optometrists, orthoptists and pharmacists, we see that they are also caught in a place of uncertainty. A workforce survey by the General Optical Council found there were 12,099 full-time optometrists in the UK; however, their distribution across the country was uneven, proving it is not just the supply of workers, but the distribution, that favours urban settings (7). Nursing is also an area of uncertainty, as ophthalmic nurses, like ophthalmologists, come through a general training process before specializing. A study by the King’s Fund found the number of nurses entering the profession in the UK did not keep pace with population growth (8). It is fair to say we have a supply and demand imbalance.

We need to prepare our workforce, patients and students for the impact artificial intelligence will have on workplaces, homes and educational spaces. We also need to prepare them for uncertainty, promoting flexibility while embracing change. It may mean encouraging less specialization or creating new roles, as well as understanding the role that technological innovation will provide. It requires training and retraining throughout our careers, as well as continually redesigning our curricula for education and training. It is about creating problem solvers, because problem-solving will always be relevant – even as the world changes.

Reimagining the future

Machine learning is slowly but surely replacing human jobs, freeing up time for individuals to take on other necessary tasks. A recent Price Waterhouse Cooper report looked at how AI, machine learning and robotics will impact the international workforce over the next few decades. They found that health has one of the lowest risks of automation between 2020 and 2035, with most jobs at risk of replacement in transport and similar industries (9). It seems the future of ophthalmic services is not in downsizing our workforce, but supporting it with technological innovation – using AI to help our professionals meet accelerating demand. The future of our profession and our workforce depends on how we decide to use technology to serve our patients better. What unfolds will not just be about technology, but about our health care system and how we can address the growing needs of society.

But the decisions do not stop there. Changes in population demographics and life expectancies are changing the skills we must build to sustain our eye hospitals. These changes, amongst others, come at a time where hospital executives are already wrestling with unprecedented disruptions, so how do we use technology and research to educate and train for the future? The answer is clear: we must nurture innovation and re-skilling as AI supports our practices. We should be creating life-long learners who are at higher levels of thinking, regardless of their role. We must encourage and support our students to become problem solvers who embrace change. Research undertaken by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists explored the confidence of UK ophthalmic trainees’ in different clinical and nonclinical aspects of ophthalmology. It was interesting to note that they reported being less confident in nonclinical skills, such as preparing a business case, while aiming to specialize in surgical sub-specialities (10). In the future, we will need ophthalmologists who are change agents, innovators and discoverers, and so we must ensure that they are skilled in areas outside their clinical specialization.

There are a number of changes that will define our classrooms, both in terms of the students we teach and the approaches we take – AI is one of them. AI will continue to advance to the point where computer-based clinical algorithms are not just being used for diagnosing, detecting and following disease in tertiary clinics, but throughout our entire health system. We will also see more computer-assisted clinical decision making. At the same time, demands on health care systems will continue to change. It is our job to make sure professionals are prepared for these changes. The Netherlands undertook two significant studies assessing major drivers for a paradigm shift in perception, learning and action about health care education (11). They found that consumer eHealth is rising with professional eHealth. In other words, more patients are better informed about their health and want to self-manage their illness with the help of technology. This more informed patient will lead to new personalized professional roles.

Reframing ophthalmic education

Truthfully, there is no single solution. Meaningful change requires a multifaceted approach. We can start by setting aside our professional divides and focusing on the challenges ahead; then we can decide, as a sector, what competencies our students, staff and patients need to address those challenges. But that is not all. Changes in ophthalmic education are not keeping pace with higher education or clinical breakthroughs. We take too long to decide how we teach, what we teach and who we teach. Some of us are too conservative and risk averse – often rightly – so we cling to historical methods of training and long-established learning practices. Not only does this mean our curricula content and delivery lags, but also that the message we send our students is in opposition to what they need to thrive in this era of digitalization and increased demand for services.

The future demands that we, as educators, are piloting, prototyping and publishing our approaches for meeting the 21st century needs of ophthalmic education. We have to allow our students to learn independently and work collectively as integrated teams. We are also going to have to infuse entrepreneurship into the curriculum because, with inevitable disruption, many of us are going to have to transform – or be transformed – to match job roles that may not exist today. Outcome-based education and backward design thinking has never been more important.

Fortunately, the silos that exist in our eye hospitals and clinics are breaking down, allowing us to deliver better patient care. We, in education, must support this change by moving towards an approach that embraces expanded roles through cross training – something that is particularly important for allied health professionals. We must also make sure that we do not deliver curricula that dates quickly. Instead, we should instil a real understanding of translational education through scientific inquiry and clinical practice. There is much that we can do with our allied health professionals and non-medical professionals to assist in supporting the gap in ophthalmic services. This approach is something we have keenly embraced at Moorfields Eye Hospital and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology. We are developing new, innovative degree programs that align with the thinking of other institutions, including the Royal College of Ophthalmologists, Royal College of Nursing, The College of Optometrists, British and Irish Orthoptic Society and the Association of Health Professions in Ophthalmology, with the launch of the new Ophthalmic Common Clinical Competency Framework (OCCCF).

However, increasing capacity through the better use of trained allied health and non-medical professionals is still in its early stages. Though change is being embraced in the UK, it is far from universally implemented. We need to work together as a community to imagine better learning management systems – ones in keeping with technological advances. And that means online resources offering 24-hour access to virtual tutors for students around the world; learning materials that know no language barriers; simulation exercises; even gamification of case studies. While we will always need clinical and surgical skill training, better use and preparation of our virtual spaces can facilitate student learning. Just as we speak about personalized ophthalmic care for our patients, the virtual space affords us an opportunity for personalized student journeys, where learning can be adjusted to the level and needs of each student. There is no reason that ophthalmic education cannot be developed to the pace and skills of our students as long as they achieve and demonstrate the key outcomes.

By collaborating in this way, letting educationalists drive what technology is used for in the education setting, rather than the other way around – with core learning across our professions in addition to specific skills – we can and will meet today’s healthcare needs. For every challenge we face, there is an equally exciting solution that we can use to drive our education agendas for students, staff and patients.

References

- Resnikoff et al, “The number of ophthalmologists in practice and training worldwide”, Br J Ophthalmol, 96, 6 (2012). PMID: 22452836.

- International Federation on Aging, “The high cost of low vision” (2013). Available at: https://bit.ly/2NFGLOw. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- Royal College of Ophthalmologists, “Workforce Census”, (2016). Available at: https://bit.ly/2XBgAbc. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- Royal College of Ophthalmologists, “The Way Forward”, (2017). Available at: https://bit.ly/2jusMXi. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- United Nations (2018). Available at: https://bit.ly/2S3MJaw. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- W Baumol, “The Cost Disease”, Yale University Press (2013).

- College of Optometrists, “The Optical Workforce Survey” (2015). Available at: https://bit.ly/2xBS5Ae. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- The King’s Fund, “Closing the Gap” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2TZe3K7. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- Price Waterhouse Cooper, “How will automation impact jobs?” (2019). Available at: https://pwc.to/2E6IQcR. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- WH Dean et al, “Ophthalmology specialist trainee survey in the United Kingdom”, Eye, 33, 917 (2019). PMID: 30710112.

- van Vliet et al., “Education for future health care”, International Journal of Healthcare, 4, 1 (2018).