- Financial advisors David Mandell and Carole Foos offer four key pieces of advice to ophthalmologists in the middle of their career

- Medical malpractice is a physician’s leading source of liability, so it is essential that doctors leverage their insurance, legal tools, and exempt assets to protect themselves from lawsuits

- Choose a suitable financial advisor, whether a broker, bank, automated investment management, or registered investment advisor

- When approaching retirement, de-risk investments by reallocating assets into increasingly conservative investments to best limit their exposure to loss

- Practice owner? Learn simple exit strategy basics – from implementing a systems-based practice to recruiting a younger ophthalmologist.

In writing this two-part article, we faced a challenge – there is simply not enough space to discuss every important planning area, such as retirement modeling, asset protection and estate planning. But what we have included are the essentials. In the first installment, we focused on selected topics for young physicians. In this article, we will discuss topics relevant for ophthalmologists in the middle part of their career and those approaching retirement. Specifically, we will cover protecting assets from lawsuits, choosing a financial advisor, de-risking retirement assets and exit strategy basics for practice owners. Let us start with mid-practice.

In this litigious society, asset protection planning is an integral part of any ophthalmologist’s comprehensive wealth plan. Unsurprisingly, medical malpractice liability is the leading source of liability on most physicians’ minds. However, ophthalmologists should also consider their liability for employee claims, vicarious liability because of employees, claims due to slips/falls at the practice, premises liability for the accidents of renters or visitors at other properties they may own, car accident lawsuits and claims because of teenage children drivers. In the pursuit to shield wealth from potential liability, it is essential that doctors employ a multi-disciplinary approach – insurance, legal tools and exempt assets all play important roles. Given limited space here, we will focus only on exempt assets, which enjoy the highest level of protection.

Exempt Assets: The “best” asset protection tools

Exempt assets are those asset classes that a state law (or federal law, if in bankruptcy) specifies are beyond the reach of lawsuits and creditors in its statutes, or case law interpreting such statutes. In other words, these are assets that the law “exempts” from creditor attachment. Because they are “exempt” regardless of the size of any potential lawsuit judgment, these asset classes provide the best protections one can enjoy.

Which assets are exempt? Every state is different, so we will focus on the three most common state exemptions here. Feel free to contact the authors to learn more about the exemptions in your state.

1. Qualified Retirement Plans and IRAs

Most, but not all, states have significant (+5) exemptions for qualified retirement plans and IRAs. Some states only protect a certain amount in such asset classes or protect qualified plans more significantly than they do IRAs.

2. Primary Residence: Homestead

Many ophthalmologists consider the home to be the family’s most valuable asset. Perhaps you have previously heard the term homestead and assumed that you could never lose your home to bad debts or other liabilities because of this homestead protection. The reality is that most states only protect between $10,000 and $60,000 of the homestead’s equity. Some states, such as New Jersey, provide no protection, while other states, such as Florida and Texas, generally provide unlimited protection for equity (with some geographic restrictions). Each state has specific requirements for claiming homestead status. Your asset protection advisor can show you how to comply with the formalities in your state.

3. Life Insurance

All 50 states have laws that protect varying amounts of life insurance. For example:

- Many states shield the policy death benefits from the creditors of the policyholder. Some also protect against the beneficiary’s creditors.

- Many states protect the policy death benefits only if the policy beneficiaries are the policyholder’s spouse, children, or other dependents.

- Some states protect a policy’s cash surrender value in addition to the policy death benefits. This can be the most valuable exemption opportunity.

Quasi-Exemption: tenancy by the entirety

Tenancy by the Entirety (“TBE”) is not a (+5) exempt asset, but it is a state law-controlled form of joint ownership that can provide total protection against claims against one spouse. TBE is available in about 20 states, although its effectiveness varies among those states. In some of these states, TBE only protects real estate; in some states, both real estate and personal property (like bank accounts) can be effectively shielded by TBE. In those states that protect it, assets held in TBE cannot be taken by a party with a claim against only one spouse. However, TBE provides no shield whatsoever against joint risks, including lawsuits that arise from your jointly owned real estate or potential acts of minor children.

Selecting an investment advisor can be an important decision for an ophthalmologist’s long-term financial security. Yet, for many, the differences among the types of “financial advisors” are not obvious. We will describe the leading options here.

1. Brokers and banks

Concerning investment advice, brokers and banks tend to be popular because they are, or they are affiliated with, the largest corporations with the most marketing and name brand recognition. A broker dealer is generally a person or firm in the business of buying and selling securities, operating as both a broker and a dealer, depending on the transaction. Some examples of such firms are national/global broker dealers, such as Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley or UBS; regional brokers include such firms as Raymond James and Edward Jones; and bank-based advisors are affiliated with large banks, like Wells Fargo and Bank of America. An ophthalmologist may consider using a broker or bank for the benefits of working with the world’s largest firms, which include tremendous research capabilities, unique investment offerings and the convenience of worldwide branch offices.

Among the reasons an ophthalmologist may consider avoiding a broker or bank is that these firms are not fiduciaries. Where the fiduciary standard requires advisors to put their client’s best interests first, brokers are subject to the suitability standard, which only requires that their actions must only be “suitable” for the client. In addition, many ophthalmologists may not be comfortable with the conflict of interest that is present in a relationship where the compensation of the individual who makes the investment recommendations is based on the product he or she uses or selects for the investor. It is important to note that most firms have realized the negative connotation the name “broker” implies and have begun referring to members of their sales force as financial advisors. To determine if the “advisor” is actually a broker, ask the advisor how they and their firm receive compensation, and whether or not they owe their client a fiduciary duty or are subject to a suitability standard.

2. Automated investment management (robo)

A robo-advisor or “robo” is an online, automated, algorithm-based portfolio management/investing service that provides little or no human interaction. Robos can be attractive to ophthalmologists because they are typically low cost and have low account minimums. An ophthalmologist may want to avoid using a robo because most robos do not provide the opportunity to communicate by phone or in person to discuss a particular situation. Most robo services available today only allow for cash transfers and deposits, and are not capable of account transfers that include established positions. This might work for ophthalmologists who are just beginning to invest. However, those individuals with existing portfolios may be practically unable to participate based on their current holdings and large unrealized capital gains. In addition, many of the current robos have other limitations, including those related to the type of accounts that can be created. For example, they are unable to create trust accounts or accounts for limited liability companies or family limited partnerships. Finally, but just as important, robos require large cash positions. These minimum cash positions can be a drag on performance. These costs may not be substantial, but they are a hidden expense that only astute investors are likely to recognize.

3. Registered investment advisor

A registered investment advisor (RIA) is an advisor or firm that is engaged in the investment advisory business and registered either with the Securities and Exchange Commission or state securities authorities. An ophthalmologist may consider using an RIA because this type of advisor must adhere to a fiduciary standard of care. Thus, they must serve a client’s best interests. Also, independent RIAs are not tied to any particular fund family or investment product. Therefore, they can typically recommend nearly any investment without financial bias. Further, RIAs use independent custodians to hold clients’ assets rather than holding the assets themselves as do brokers and bankers. Finally, RIAs typically charge a simple, transparent fee based on a percentage of the assets they manage. An ophthalmologist may want to avoid working with an RIA if access to firm branches nationwide, sophisticated research departments or complex financial products is a priority for them. Even the largest RIAs could be lacking in these areas compared with the largest banks and brokers.

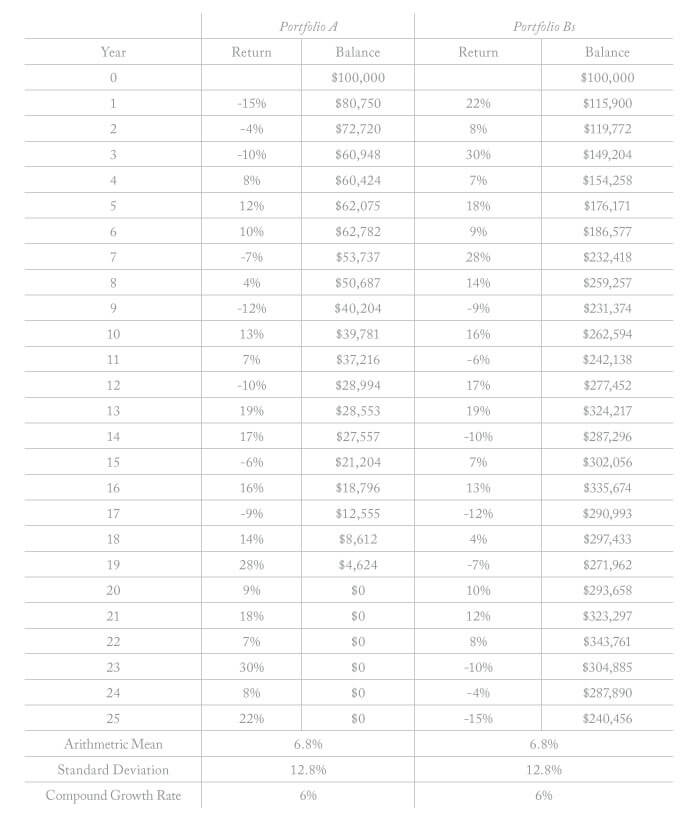

As ophthalmologists age, they should reallocate their assets into increasingly conservative investments to best limit their exposure to loss. The idea of reallocating to more conservative assets can be troubling to those who are focused on maximizing returns because conservative investments tend to have limited upside potential. To understand why this move is often more beneficial than seeking higher returns in later life, an ophthalmologist needs only to be familiar with sequence of returns risk. Sequence of returns risk is the danger that the timing of liquidation and withdrawal from a retirement account will coincide with a downturn in the market. If it does, then it effectively reduces the overall potential performance of the entire portfolio because a greater number of shares will need to be liquidated to get the income expected, thus leaving fewer shares in the portfolio to grow. Sequence of returns risk may not be important during a physician’s early or middle years, when time horizons are long, but during the withdrawal phase it is one of the most critical factors in the overall success of a retirement plan, making it a higher priority than chasing returns.

Readers are likely to be shocked by the results of the above illustration. The hypothetical example demonstrates two physicians taking five percent of the initial principal. Portfolio A and B have the exact same mean return over a 25-year period with identical risk (i.e., standard deviation). Portfolio A ran out of money. Portfolio B experienced a 140 percent increase in value at the conclusion of the 25-year period. Why? Because of the sequence of the returns. Neither investors nor advisors can control the timing of stock returns, but they can control risk. By managing risk more tightly when approaching retirement, physicians can limit the range of possible outcomes, ultimately increasing odds of success.

Ophthalmologists who own their practices have another challenge in pre-retirement years – how to structure the practice for a potential exit. These tactics should be considered:

1. Implement a systems-based practice

Any business exit strategy consultant will explain that, for any business, it is crucial to systemize as many of the business operations as possible. When there are systems and written procedures for every element of the business, it is that much more valuable to a potential buyer. In ophthalmology practices, for every operation other than the ophthalmologist’s medical decisions and handiwork, it is no different.

2. Recruit a younger ophthalmologist

Because the practice of medicine is tightly controlled by regulations, many ophthalmologists do not have the possibility of selling their practices to non-physician investors – although this has been changing rapidly with the entrance of private equity investment into medical practices in general, and ophthalmology practices in particular. Many ophthalmology practices that eschew private equity will likely be sold internally to a younger ophthalmologist who starts as an associate and then becomes a partner and then the ultimate purchasing party. If this is a possibility, recruiting that physician and seeing if he or she is the right fit cannot be delayed until close to the planned exit of the senior ophthalmologist. It may take five, seven, ten years or longer to find the right associate, train them properly, see that they can handle the patient load and determine their financial ability to purchase the practice shares at a price that both parties think is fair. In addition, getting the younger physician to buy in on the long-term plan is imperative, especially the formula on practice value and possible ancillary issues – such as fair rent, if the senior ophthalmologist owns the building and will continue to after the sale.

3. Design a compensation plan that fits the long-term plan

Another tactic for ophthalmologists to consider when recruiting and hiring a younger associate is to implement a compensation package that ties to the long-term plan. For example, a non-qualified plan could be designed so that the funding of the plan grows tax beneficially and is owned by the practice for years, even decades. If the associate hits their goals and stays for the duration, they vest into the plan. If they do not hit their goals, or leave the practice, the entire value stays with the practice (i.e., the senior ophthalmologist). This may not only motivate and incentivize the associate to stay for years, but could also provide a significant part of their buyout fund if the timing of vesting coincides with the senior ophthalmologist’s exit and sale of the practice.

To receive free print copies or ebook downloads of For Doctors Only: A Guide to Working Less and Building More and Wealth Management Made Simple, text OPHTH to 555-888, or visit www.ojmbookstore.com and enter promotional code OPHTH at checkout.