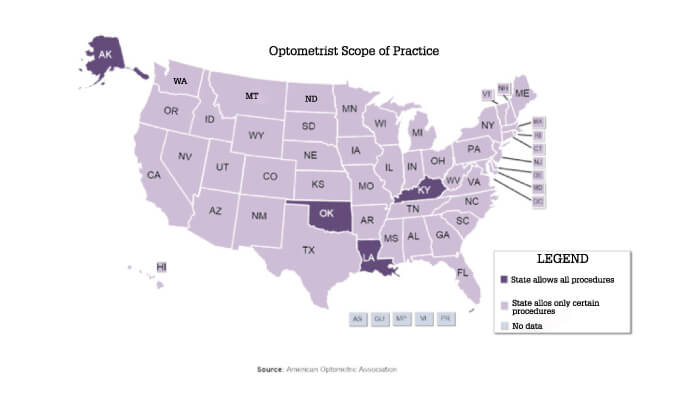

I graduated from optometry school in 1981 and continued my education at a medical school, where I graduated six years later: I have seen eye care from the point of view of both an optometrist, and an ophthalmologist. More recently, I was the chairman of an ASCRS committee that tried to involve optometrists in ASCRS activities; sadly, the project did not turn out well, and the committee was disbanded. The debate between the two professions has been a politically challenging issue for decades. There are economic benefits of being able to perform surgical procedures or prescribe certain medications and, at the institutional level, things are not always amicable. There are currently four states in the US that allow optometrists to perform surgical procedures: Alaska, Kentucky, Louisiana and Oklahoma, but more states might join this group in the future. Once critical mass in a particular state is reached, legislation will follow. Less invasive procedures currently performed by optometrists might in time evolve into more complicated ones.

This relationship has been difficult throughout my 38-year career. In the early 1980s, optometrists wanted to get drug-prescribing privileges for diagnostic drops. The ophthalmology profession fought against this move by the optometric profession, but lost, and these days every US state allows optometrists to prescribe these drops. A similar process followed in the case of therapeutic drops, and now surgical privileges are on the table.

This situation is specific to the USA, of course. Depending on the particular country’s regulation, education and training systems for both professions, practice varies greatly. Aiming at expanding a profession’s privileges is a normal thing, provided it is done with patients’ safety as the primary concern; in fact, some ophthalmologists are fighting to expand their profession into new fields, such as plastic surgery, which borders with oculoplastics. It is interesting to note that even though a profession might hold certain privileges, not all of its representatives use them. In the US, even though optometrists have fought for and won the ability to prescribe therapeutic medications, such as glaucoma drops or antibiotics, relatively few optometrists regularly prescribe these. Many practices have very successful working relationships between ophthalmologists and optometrists, with clearly defined specialty areas, and effective mutual referral systems.

From my vantage point

My personal relationship with optometrists is a very positive one. I work with them a lot, and I believe they are critical to the delivery of eye care in the US. In the next few decades the number of ophthalmologists is unlikely to increase and the number of patients will increase dramatically.

It would be impossible to deliver the care that people need without optometrists. There is no question in my mind that they should be a vital part of the team, the question is: what role they play in that team, including the exact scope of their activities. There is a whole spectrum of specialties among the optometrists I regularly work with, and some of my optometrist colleagues are of the opinion that they should be performing some surgical procedures, like their colleagues in some parts of Europe, or in the US states mentioned earlier.

Currently, a lot of responsibility in the USA is devolved to individual practices. Outside of state regulation, they have autonomy to decide whether specific types of surgery are done by the surgeon, or by a physician assistant, who receives mostly technical training around how to do the surgery and has little experience compared with a doctor, but is legally allowed to do surgery or administer intravitreal injections under a surgeon’s license. This is specified in the practice’s protocols, but it is ultimately the surgeon who is liable. It’s just one example of how physician assistants and nurse practitioners are taking on more and more responsibility in eye care to assist in the delivery of care.

Over the horizon

Over the next two or three decades, we are not expecting to have more ophthalmologists trained and practicing than we have today. Demands from the aging society, on the other hand, are steadily growing: we are projected to have twice as much work in 20 years’ time as we do now. With so few practitioners expected to do so much work, new scenarios have to be developed. The UK, which suffers from tremendous pressure of intravitreal injections volumes, is exploring the possibility of nurse practitioners administering injections. Such reports create a stir among US ophthalmologists, but it is simply addressing the burden of work under which our profession finds itself. In time, our delivery systems must be adjusted to match the available workforce with the needs of the population.

What I believe optometrists require is the cognitive process behind examining a patient – seeing the big picture. And that is actually more complex and in some ways more difficult than learning how to do a YAG laser procedure. The ability to perform complex processes is important, but knowing which complex process to apply is vital.

US optometry practice, prescriptive and surgical authority timeline (1, 2).

1961 A bill is introduced by Pennsylvania optometrists to authorize the use of ophthalmic diagnostic pharmaceutical agents – it is defeated.

1971 First DPA Law passes in Rhode Island, giving specifically authorization to optometrists for using ophthalmic drugs for diagnostic purposes. (By 1989 all states and DC had DPA laws)

1973 Optometrists in North Carolina are authorized to use and prescribe pharmaceutical agents for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

1976 First TPA Law passes in West Virginia, permitting the use of therapeutic drugs by optometrists. (By 1998 all states and DC had TPA laws)

1981 US Congress expands optometric coverage under Medicare to enable reimbursement for procedures performed on aphakic patients.

1986 Medicare parity legislation allows optometrists to be reimbursed for health-related services performed on non aphakic patients. The law became effective in April 1987.

1998 Oklahoma enacts the first state law specifically authorizing the use of lasers by optometrists for certain treatment purposes.

2005 Oklahoma regains the right to use lasers after losing it.

2011 Kentucky optometrists are allowed to perform certain injections and laser procedures under new legislation.

2014 Louisiana becomes the third state to allow optometrists to perform surgical procedures.

2017 Under Alaskan House Bill 103, optometrists in the state can perform anterior segment laser procedures, including YAG capsulotomy, SLT and LPI.

References

- American Optometric Association, “History of Optometry” (2010). Available at https://bit.ly/2jNkCwW. Accessed September 5, 2019.

- Review of Optometry, “125 Years of Optometry: A Timeline” (2016). Available at https://bit.ly/29PvC9e. Accessed September 5, 2019.