- Female representation in ophthalmology is similar to other medical specialties

- Clinical leadership roles still appear to be unpopular among doctors, which may explain why female representation in leadership forums has grown quicker than in academia

- Gender and ethnic diversity in leadership has a direct positive effect on productivity

- Networking and support agencies – and a clear route to success – can help women pursue leadership positions.

Towards the end of my registrar training, a guest speaker attended our departmental teaching session – and suddenly my eyes opened to the impact of clinician leadership on the provision of high-quality healthcare. In my mind, until that point, clinical excellence meant individual interactions with patients, rather than the environment in which I worked, and its impact on good clinical decision making. After attending that teaching session, I quickly enrolled in a Healthcare Management MSc distance learning course with London University. Subsequently, I built on this foundation by becoming a leadership fellow with the Health Foundation, and a European Leadership Fellow with INSEAD Business School. These fellowships coincided with my appointment as a consultant at Moorfields Eye Hospital. I have gone on to be a Clinical Director, and now Chief Surgeon at the hospital.

Although my personal experience of leadership as a woman has predominantly been a positive one, women are undoubtedly underrepresented in leadership roles across the NHS. The 2018 workforce census published by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists reports that 31 percent of consultants in the UK are female (1). This is an improvement on the 2016 figures of 24 percent, but it still shows how women are under-represented, given that 58 percent of trainees in ophthalmology are female. In ophthalmology, the opportunities for women are similar to the statistics seen elsewhere in medicine. NHS Digital reported that 26 percent of consultants in medicine are female, however it is noteworthy that in surgical specialties only 12 percent of consultants are female (2).

In the corporate environment female CEOs are still unusual. Of the CEOs that make up the 2018 Fortune 500 list just 24 (or 4.8 percent) are women (3). The statistics for female leadership in healthcare are more encouraging, with the proportion of women on Trust boards being 42.6 percent, and 39.5 percent on clinical commissioning groups’ (CCG) boards. However, only 24.6 percent of medical directors are female. In the context of 77 percent of NHS workforce being women, we still have a long way to go (3).

My personal observation is that clinical leadership remains a less recognized route in medicine when compared with academia or medical education, both in terms of career pathways and peer recognition. Clinical leadership roles are still unpopular among doctors, often being viewed with suspicion. The relatively low status of clinical leaders amongst their peers, with the exception of medical director roles, may partly explain why female representation in leadership forums has grown quicker than in academic arenas.

Although leadership and management skills are now included in medical school and junior doctor curriculae, it is difficult to predict whether this will change the status of clinical leaders in healthcare settings in the future, particularly in the context of clinical excellence awards becoming devalued, and the work required to achieve them being out of step with the rewards of other endeavors, whether they be private practice, work-life balance, or academic achievements. It is also noteworthy that leadership roles in the NHS lend themselves to women with families, if they are adequately recompensed in job planning, as it is easier to organize time flexibly, compared with direct clinical care sessions such as clinics or surgical lists.

One may ask, why is it important to see more diversity, whether it be gender or ethnicity, in leadership positions? Many examples in the corporate sector prove that increasing diversity has a direct positive effect on productivity. In 2018, the Boston Consulting Group looked at 1700 companies across eight countries, of varying sizes and from different industries. They showed that diversity was related to increased revenue due to innovation, and that it helped build a culture where “out-of-the-box ideas” were encouraged and nurtured (4). Moreover, in the context of the public sector, there is growing evidence suggesting that, when the leadership of an organization reflects the diversity of its client base, the services it offers are more responsive and representative of its client demands. Most would agree that in the current NHS environment, these qualities are paramount to its survival.

If it is well recognized that female leadership increases the performance of organizations, why is it that we have seen such a slow change in the representation of women in leadership roles? Interestingly, the barriers to female leadership can come from both male and female workers. Although the qualities of leadership may be the same for all sexes (for example, being organized, ambitious, and intelligent), the way those qualities are applied does result in specific management strategies and leadership styles. Certainly, traits that are often quoted as being more prevalent in female leaders includes empathy, listening and collaboration (see Box: Female leadership styles).

Ana Marinovic and Steve Tappin found that there were, broadly speaking, four main female leadership styles (5):

- Female Pioneers: Often with leadership styles that resonate with more masculine environments, such as forthright and “no-nonsense.” Although they are often pioneers in male-dominated environments, they may sometimes be described as “the token woman.”

- Feminine Leaders: Women who have been exposed to more equality in their upbringing, both professionally and at home. Often of generation X, they have the confidence to bring “feminine” qualities to work. Their qualities are described as being able to listen, care, understand and communicate well.

- The Integrated Women: Women with strong leadership qualities and influence through their ambition and drive to succeed personally, and to support equality in the workplace. There is less of a separation between work and home; these women have an influential nature, and are very good at collaborating, empowering, connecting and co-creating with both men and women.

- Women of Inspiration: These women come from all generations and generally embody all of the other leadership types. They are driven by a higher purpose, are often globally recognized, and have broken free from male-dominated leadership constraints.

Barriers to female leadership also originate in the perception others have of female leadership styles. For example, when asked to imagine a leader, a male leader is often described by both male and female respondents. Further, men are often described as being more decisive or better at solving problems, even though research would suggest that this is not the case. It is also notable that in describing female leadership, less attractive descriptions are frequently used for the same traits; for example, bossy versus decisive.

Women are often left with the dilemma of either adopting masculine leadership styles or being considered a poor leader by both male and female colleagues. Indeed, research has shown that 75 percent of female managers feel more comfortable with male leaders, either due to social norms of patriarchy or experience of the “queen bee” phenomenon, a process by which females compete with each other, sometimes sabotaging careers of female peers (6).

At Moorfields, there has been significant encouragement and mentorship of female leaders within the organization. Forty-one percent of the consultant body is female, above the national average for ophthalmology. Leadership courses and fellowships have actively been encouraged. Moorfields is perhaps also different from national statistics in terms of clinician management. There are many female leaders both in clinical services, education and academia; indeed, the Chairperson of the Board is female. And that may explain why my experience overall has been a positive one. I think it is also important to highlight that my leadership mentors have been predominantly male, and I have been very fortunate to work with medical directors and chief executives who have been extremely supportive and encouraging in their both time and financial support. It is not true to say that female empowerment only stems from female mentors.

I do, however, see it as an important aspect of my role to encourage female trainees to make career decisions based on their talents, and not on stereotypical bias. There are a number of female networking and support agencies in existence (such as Women in Vision UK, Women in Ophthalmology and Ophthalmic World Leaders) to encourage women to take a leadership roles and also academic roles, and I hope that one day we will no longer feel that they are required to encourage women to take up leadership roles.

In this modern debate about male/female equality in the workplace, we must not simplify the argument. Not all women have the same work ethic, wish for family or work-life balance. Some men will have more in common with their female counterparts. Increasingly, women make the major financial contribution to household incomes. We do however need to recognize that diversity in the workplace at leadership levels whether it be gender, ethnicity or disability, enhances our ability to deliver the patient centered care we aspire to.

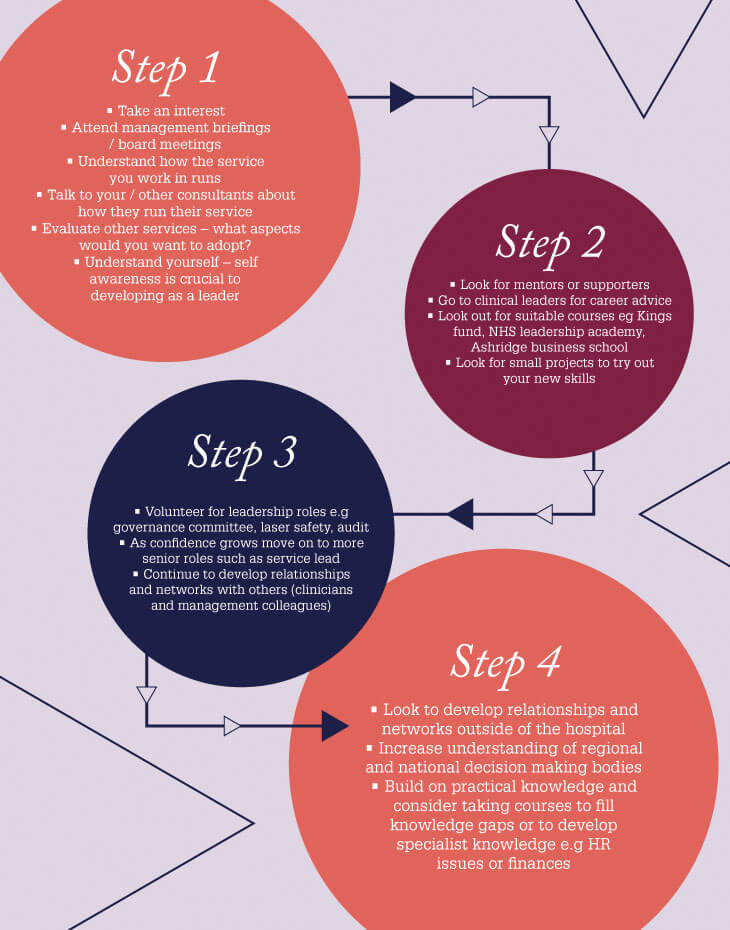

The route to leadership

References

- The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, “Workforce Census 2018” (2018). Available at: https://bit.ly/326tMIJ. Accessed July 3, 2019.

- NHS Digital, “NHS Workforce Statistics – March 2019” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/2XppiOs. Accessed July 3, 2019.

- Fortune, “Fortune 500 List” (2018). Available at: https://bit.ly/2J8fEXN. Accessed July 3, 2019.

- Boston Consulting Group, “How diverse leadership teams boost innovation” (2018). Available at: https://on.bcg.com/30hp1uj. Accessed July 3, 2019.

- HR Magazine, “The four types of female leadership” (2017). Available at: https://bit.ly/326vRV3. Accessed July 3, 2019.

- K Reddy, Wisestep, “Male vs Female Leadership: Differences and Similarities” (2018). Available at: https://bit.ly/2F2THrv. Accessed July 20, 2019.