In 1968, Australian ophthalmologist Fred Hollows was in his Sydney eye clinic when two Aboriginal Elders presented with eye problems he’d never seen before. After treating the men, Hollows was invited to visit the camp where they lived – Wattie Creek – in the remote Northern Territory. He was shocked by what he saw: blinding trachoma, a disease he didn’t think existed in modern-day Australia.

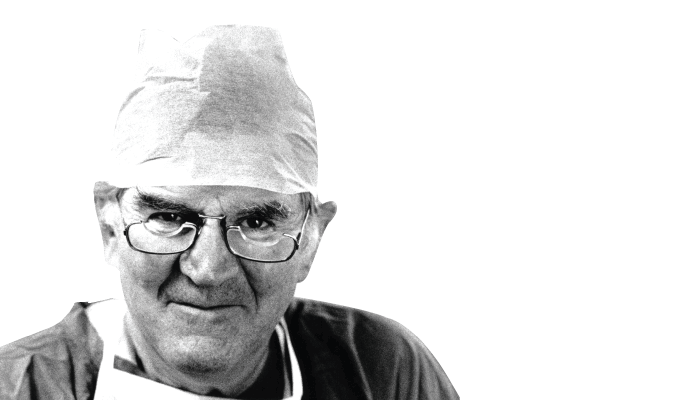

Fred Hollows was more than an ophthalmologist. He was a social and political activist who believed that the basic attribute of mankind was to look after each other. He was a no-nonsense, larger-than-life character who embodied the Australian values that everyone deserved “a fair go.” It was these qualities that endeared him to the Australian public, and earned him the honor of “Australian of the Year” in 1990, three years before he passed away. To this day, almost 80 percent of Australians can still identify Fred Hollows, and the organization founded in his name remains one of the nation’s largest NGOs.

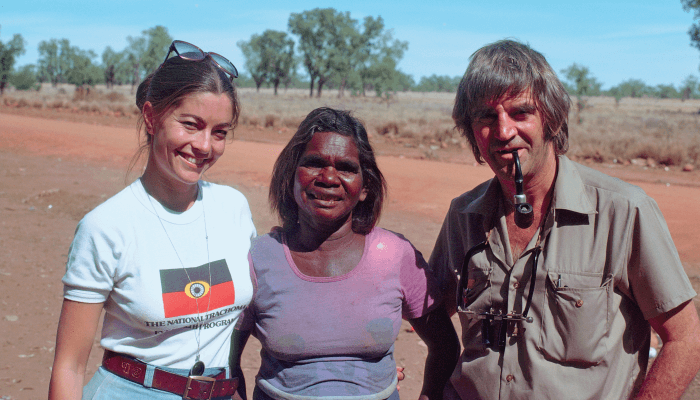

The Fred Hollows Foundation continues its sight-saving work in the areas where Hollows’ mix of medical outreach and advocacy started – in outback Australia, Vietnam, Nepal, and Eritrea. Over the past two decades, its scope has expanded rapidly, now extending to more than 25 countries. After seeing first hand the devastation of trachoma at Wattie Creek in 1968, Hollows gathered a team of eye health professionals and social activists, lobbied decision makers, raised money, and delivered the National Trachoma Program.

Over two years from 1976 to 1978, the Program representatives visited more than 100,000 people in remote and rural Australia, treating people in 465 communities. Their hard work halved the rate of blindness for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

The National Trachoma Program’s success was based on the active involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in its design and implementation. This approach remains fundamental to the DNA of The Foundation, and drives its commitment to improving the eye health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. In 1985, Hollows visited Nepal, Burma, Sri Lanka, India, and Bangladesh on behalf of the World Health Organization. Two years later, he visited Eritrea, whose people were then in the midst of a civil war. These experiences shaped Hollows’ outlook. He understood the barriers to providing first-class eye healthcare globally, and decided on a plan to overcome them. He followed a simple but effective formula that would quickly establish The Foundation as one of Australia’s largest international development organizations.

The approach was straightforward: donating capital and skills, and training people to look after themselves. This model remains at the heart of The Foundation’s work. Hollows’ vision rested on two pillars. First was the development of intraocular lens (IOL) factories in developing countries like Nepal and Eritrea. These factories would develop affordable, high-quality IOLs, produced at a fraction of the cost of those made in industrialized parts of the world. Once established, the factories would also empower those countries to take the lead in developing an independent commercial enterprise that could earn valuable export income. Within five years, the factories were producing enough lenses for local demand, and were soon exporting to 39 other countries.

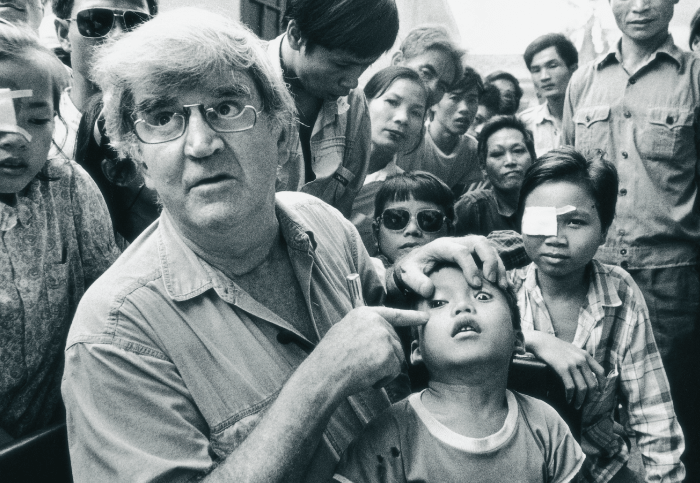

Second, Hollows invested heavily in training eye surgeons in developing countries in modern surgical techniques. In 1992, he went to Vietnam to learn more about the state of cataract surgery there. He reassured the eager eye surgeons that he would be back to train them in modern cataract surgery, and deliver equipment and surgical supplies. Hollows would never leave a job half-done, and despite fighting a tough battle against cancer, he checked himself out of hospital to deliver on that promise. By the time of Hollows’ death in 1993, his “train the trainer” model had laid the foundation for the development of a considerable eye health workforce in Nepal, Eritrea, and Vietnam.

Delivering Hollows’ vision fell to his wife, Gabi, and the band of committed fellow travelers who had convinced him to establish an organization with the strategy and financial capacity needed to achieve his goal of ending avoidable blindness. (The Foundation was established around the dinner table of the Hollows’ Sydney home, with the first board meeting held at the back of the ophthalmology department at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Sydney.)

Today, Hollows’ vision has become a global legacy. Over the past five years, The Foundation, working with its partners, has supported 3.6 million eye operations and treatments, trained some 303,000 surgeons, health workers and teachers, and provided $16.5 million worth of equipment and infrastructure. Empowering local people to deliver local services in partnership with health authorities and other partners – that’s the vision I’m doing my best to uphold as CEO.

As the world’s population ages, we are acutely aware of the challenges ahead. The Foundation’s new five-year strategy is geared towards urgently scaling up efforts to end avoidable blindness – in particular, cataract and the increasing prevalence of refractive error. The Foundation also has a strong focus on improving women’s access to eye health through a new initiative called “She Sees” (Editor’s note: read more in our February 2020 issue), which places women and girls firmly at the center of our programing, service delivery, partnerships, and global advocacy work.

None of this would have been possible without Hollows. He was not a charity worker who handed out money, fixed eyes, and walked away. He was a social activist, who was wholly committed to creating sustained systemic change to ensure that the highest standard of care was available to those who could least afford it. He is gone, but he will never be forgotten.