This Is America

The untold story of America’s first Black ophthalmologist, David K. McDonogh

By Richard Koplin

Richard Koplin

More than 10 years ago, I began an initiative to re-invigorate the pre-med program at my alma mater, Lafayette College, intending to name it after an illustrious physician graduate of the college. Diane Shaw, the school’s archivist, introduced me to the broad brushstrokes of the story of a New Orleans’ slave named David K. McDonogh who became the first Black graduate of the college (1842) and who, it was claimed, became a physician in New York City in the mid-1800s. That very idea, a slave becoming a NYC physician in 1850, and a graduate of my alma mater, was captivating. I was hooked. Little did I know that this adventure would lead me to my own front door.

The complexities of historical research

Over the following years, through financial and investigative contributions by me and the College – the latter giving us the ability to employ a bevy of professional researchers, including genealogists and historical experts – we gradually uncovered David’s story. Students excited by David’s life and times at their college signed on year after year as volunteer researchers. The quest took us far and wide: from visits to archives held by Tulane University, numerous historical societies, and a host of libraries to government historical repositories as far away as Liberia.

Time is a cunning enemy to researchers of history. Materials are lost to posterity; and truth is eroded as interpretation is often twisted or embellished or simply misrepresented out of ignorance. Finding “facts” that can be corroborated and originate via respectable and reliable primary sources becomes paramount.

Giving David his due

After almost 200 years, there was still one wrong we considered might be righted on David’s behalf. In 2017, we took the initiative to educate the administration of the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University of his story. The goal was to impress upon them the importance of the school’s historic failure based on the racism and hubris of the time, and get them to grant David a medical degree. We suggested that the degree could be provided to David’s great-great granddaughter, who had been found by our researchers. After some procrastination on their part, the degree was finally conferred at the medical school’s graduation ceremonies in 2018.

Remarkably, after seeming social advancements codified by American law (the 14th Amendment in 1868, and almost 100 years later The Civil Rights Act of 1964), the resistance to a fully integrated democracy has been on full display during the past four years. David’s story resonates as a clear example of the struggle that people of color faced then, as well as now, as they aspired to enjoy the advantages of full political and economic parity with white America.

On a positive note, even in the face of overt racism – and even slavery – David did find allies among white individuals mindful of the inequities of life for Black Americans, and who took it upon themselves to rectify them; John Kearny Rogers and Walter Lowrie, among them. And, remarkably, the medical profession at the time did embrace David as one of their own. I am confident that after a particularly ugly and politically chaotic period in America, fair-minded and thoughtful citizens will step up to bring closure to a divisive period in our history, allowing us to move forward for all our citizenry and reignite this experiment known as American Democracy.

Travelling Through Time with America’s First Black Ophthalmologist, David K. McDonogh

We present a timeline of McDonogh's life, from his days as an enslaved person to his Columbia graduation – 125 years after his death.

David's story

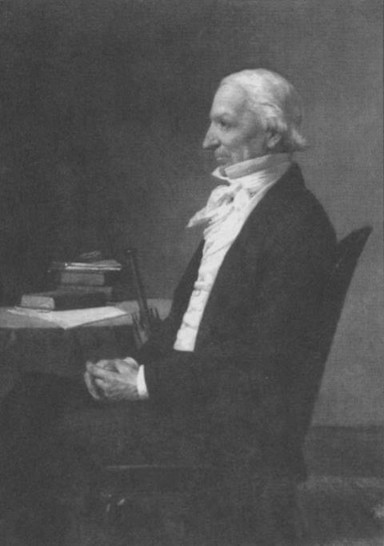

Slavemaster John McDonogh

In 1838, David K. McDonogh, a 19-year-old slave, arrived at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, along with a fellow enslaved person, Washington McDonogh. Both young men were sent to the college by iconoclastic New Orleans plantation owner and mercantilist, John McDonogh (right). With more than 500 slaves, he was arguably one of the wealthiest men and largest landowners in the south.

Both David and Washington were the beneficiaries of John’s secret experiment, initiated in the mid-1820s. McDonogh provided his slaves an avenue to freedom by working an extra day a week for 10 to 15 years. But the experiment came with a non-negotiable caveat – under the auspices of the American Colonization Society, his freed slaves were obligated to emigrate to the nascent Republic of Liberia. But John McDonogh was not content to free all his slaves to an unchartered destiny. Instead, he decided to educate several of his brightest slaves to serve as stewards of the newly formed Black democracy, still in its infancy. David and Washington, who both elected to take their master’s surname, were examples of John McDonogh’s odd relationship to slavery.

On February 1, 1838, John McDonogh wrote a letter of introduction to Walter Lowrie, an esteemed US Senator (and in 1821, a strong voice opposing slavery in the soon-to-be-minted state of Missouri). Lowrie was secretary of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions and McDonogh, also a devout Calvinist, no doubt found fellowship with Lowrie:

I beg leave to observe that among my Black family, I have two Youths, (Slaves) of great promise, of the age of nineteen and twenty years, who are remarkable at that early period of life for their intelligence, knowledge, and solidarity of judgment, their pious, and tractable dispositions, whom I offer to your Society, to be given a Religious Education, preparatory to their becoming missionaries of, the Gospel in the land of their forefathers.

Lowrie was ultimately engaged by John to act as David and Washington’s legal guardian while they attended Lafayette College. Washington left Lafayette prematurely with his family and 90 of John’s other slaves to spend his life as an educator and government administrator in Settra Kroo, Liberia. Lowrie clearly found John McDonogh's description of David to be apt. David was a unique individual, so much so that even John, a slave owner and a racist, spoke enthusiastically about the then 19-year-old. David's understanding with his slave owner determined that he was to attend Lafayette College and upon graduation emigrate to Liberia where, John openly mused, he might become its President (“another Madison,” he related to Lowrie).

A student drawing of Lafayette College about the time that David matriculated and was soon to graduate.

David arrived at Lafayette in uniquely challenging conditions. There were, of course, the typical freshman concerns. In a very familial letter, having never experienced winter conditions in the North East, David wrote John asking him to forward a hat and clothing he had left in a drawer in his quarters and some funds to buy a watch, which his classmates wore openly as status symbols. (To this request, John asked Lowrie if there were no clocks on campus. Nonetheless, he did send funds to purchase the watch. Teenagers will be teenagers.)

More concerning, however, was David’s status on campus. Although David had been technically freed when entering Pennsylvania, he was segregated when taking classes and meals. However, it was apparently difficult to keep the young students apart and, by all accounts, David was a popular figure on campus. Even the president of the college wrote that “no student in the College mingles more freely with the other students than he.” David bristled at the college president’s attempts to prevent him from integrating on campus or making social contacts in the college town. David taught Sunday school at a local Black church and quickly became popular with the children. The head clergy, in an apparent pique of jealously, asked Lafayette’s President to forbid his participation in church functions. This led to a show-down where David lobbied the school’s tutors and students for assistance in his cause. Eventually, David was forced to back down.

David spent two years at Lafayette in a basic preparatory education and then four more years in a more formalized college academic structure. David was a very capable student but was frustrated by the institutionalized racism he experienced and struggled without the promise of a tangible future. Though this is not unusual for any young adult, David’s troubles were magnified by the challenges of being a Black man in antebellum America and the over-riding thought of eventually leaving for Liberia.

Despite his seeming disdain for his condition at Lafayette, he wrote to Lowrie that: “I am acquainted with, and possess the goodwill of, and am very kindly treated by all the students and professors.” He went on to say that this was of great advantage to him.

By his junior year, David began to lobby for an opportunity to study medicine as part of his curriculum. His persistence paid off and, eventually, John gave grudging approval for David to apprentice himself to a local Easton physician. David could barely contain his enthusiasm. In one letter to John, he wrote: “I forgot to inform you in my last letter of my Practice of Medicine. I have bled three persons since I received my lancet. In one case, I stuck a woman and the blood flew up to the ceiling, over the bed, husband and everything else that was in its way….” The sincere words of a young man who had found his passion.

But complications soon arose. With graduation barely six months away – when David would become Lafayette’s first Black graduate – he proclaimed that he would not honor his contract with John to emigrate until he completed a formal medical education. Frustrated and fully aware of David’s implacable spirit, at first John attempted to threaten him by suggesting to Lowrie that he could have him forcibly brought back to New Orleans in bondage, and that he should relate this to David (memorialized in one dramatic passage in a letter to Lowrie). But John soon realized he had lost the battle of wills and wrote to Lowrie that he was washing his hands of David (although he would continue to pray for him):

I advise you sir to see David at as early a day as your occupations and leisure will admit: and if you find his determination such, stop I pray you, Sir, instantly all further expense on account – even one cent! Notify the President of the College that you will not pay for one single hours’ tuition or Board, more.

Lowrie facilitated David’s graduation but afterward, rudderless and without funds, he was seemingly without options. (Lowrie informed David that no credible medical institution was willing to admit a Black man, even with his academic record and his apprenticeship to a local physician.) David’s anger and despair overflowed; his feelings apparent in this eloquent passage written to John and Walter – a letter that strikes at the heart of race relations of the time, and reverberates loudly still, nearly 200 years later.

After waiting with the most sanguine of expectations, I received your letter of the 23rd. Nothing could be sadder or more disheartening to me – this devotion from moral rectitude on the part of the medical faculties.

There exists in the breast of the white man an inveterate hatred against the black man: and the very name negro – the very thought that he is endeavoring to raise himself above the groveling elements of brutality – draws that hatred into focus, which radiates that nefarious past called Prejudice.

Permit me to say that the Refusal on the part of the medical faculties, and the worse than slavish treatment which I have suffered here, and from those, too, who are looked upon by their Kind as saints on Earth, have given me the strongest Reasons to distrust the fidelity of the white man. Therefore sir – with due deference to your honor, I have resolved to cover my sable Brow with a cloud of despair and never more to look up to the White man, whatever may be his profession or condition in society, as a true friend. These concluding remarks are general and consequently liable to honorable exceptions.

Perhaps the “honorable exceptions” that David alluded to materialized in the guise of two sympathetic individuals. Lowrie, stationed at the time in New York City, likely facilitated David’s move to the City and introduced him to John Kearny Rodgers, an eminent New York physician and the co-founder of the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary – America’s oldest specialty hospital. Rodgers, a lay minister, was stung by society's unwillingness to care for those less fortunate (as seen in his preamble to the founding of the Infirmary in 1820).

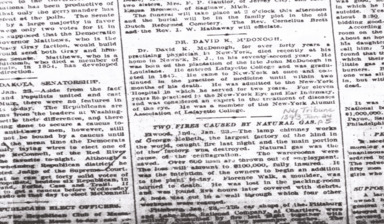

David McDonogh's obituary describing his New York Eye and Ear Infirmary affiliation, giving proof to his station as America's first professionally trained Black ophthalmologist.

Rodgers championed David’s cause and mentored him through his medical studies at the College of Physicians and Surgeons (later Vagelos School of Medicine at Columbia University), in spite of objections from the dean of the medical college who, at the time of graduation, refused to award David a diploma. Nonetheless, David’s peers embraced him as a colleague and Rodgers provided him a staff position at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, where he practiced ophthalmology for 11 years. It was said: “he did excellent work and was frequently in demand as a consultant.” When John Kearny Rodgers died in 1850, David took Kearny as his middle name.

David McDonogh's tombstone.

David began a practice on Sullivan Street in the Greenwich Village, an area of the City that was remarkably integrated at the time, and practiced medicine until shortly before his death in 1893. He is buried beneath an impressive monolith in famed Woodlawn Cemetery in New York City’s Bronx.

In league with Frederick Douglass, David became active in the abolitionist movement and a champion of workers’ rights. David’s commitment to social justice is reflected in his dedication to the progressive movements of the time. In 1890, he served as a delegate to the National Colored Convention in Washington, D.C., where he was elected one of its vice presidents.

David married Elizabeth Van Wagoner and of their three children, only one survived into adulthood. Our research has identified one surviving member of David’s family and we have introduced her to her remarkable great, great grandfather’s legacy. In 2018, with the assistance of Diane Windham Shaw (Lafayette College’s legendary archivist), we presented our research to the Dean of Academic Affairs of Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. After some temporizing on the College’s part, they agreed to confer David with a posthumous medical degree, presented to his great, great, granddaughter at a graduation ceremony in 2018.

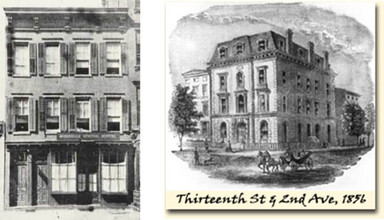

New York Eye and Ear in the 1850s, when David McDonogh attended.

For his part, John Kearny Rodgers fulfilled his mission by providing David the opportunity to become the only slave to gain a medical education, to become America's first Black ophthalmologist, as well as the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary's first Black attending. It would take more than 100 years for the Infirmary to provide staff privileges to another Black physician, Harold Najac.

As a testament to David K. McDonogh’s legacy – appreciated by both Black and white members of society – the McDonough (sic) Memorial Hospital opened on West 41st Street in 1898. It was New York’s first interracial hospital. The hospital survived just six years but in 1918, plans for a second McDonough Hospital at 133rd Street and Fifth Ave in Harlem were celebrated. Unfortunately, even with tremendous expectations and community support, the hospital never materialized.

Postcard of the McDonogh Monument, Lafayette Square, from the collection of Ned Hémard.

As testament to David’s legacy, there are now McDonogh Societies at Lafayette College, New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mt. Sinai, and the David K. McDonogh Society, under the auspices of the National Medical Association, as well as a Scholarship program at the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Despite all we’ve discovered about the life of this extraordinary man, one piece of the puzzle has remained elusive – no portrait or photo survives to put a face to his remarkable achievements.

Richard Koplin is Co-Director of the Cataract Service at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mt. Sinai, New York, USA.

Setting the Past Straight

An archivist’s role in restoring Black pioneers to their true place in college history

By Diane Windham Shaw

Diane Windham Shaw

In 1986, the year after I came to Lafayette, an article was published in the college magazine about David McDonogh – a slave who had been sent to the College to be educated in the 1830s and who had gone on to become a physician. As an archivist, I was intrigued by this story that had not made it into the history of the institution. Not long after, I was asked for the names of notable alumni in medicine that the college could use for a group that would serve as advisors to pre-med students. I offered the name David McDonogh. At that point, there was much we did not know, but, with the pivotal support and partnership of Lafayette alumnus Richard Koplin we were about to change that. Over the course of a decade, with the help of our students, we began piecing together McDonogh’s life. I spent a lot of time at the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia. I traveled to other collections at Tulane, LSU, UNC at Chapel Hill, and Syracuse University.

Some of our first clues came from a 1980 article written by a scholar on the Presbyterian involvement in Liberia, which cited 12 letters written by David McDonogh located at the Presbyterian Historical Society. For a long time, we thought those were the only existing letters, but, as it turned out, there were scores. One of the major discoveries was a draft of the letter by his guardian, Walter Lowrie, emancipating him about three weeks after he had arrived on campus. One of our most elusive challenges was connecting McDonogh with the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York (Columbia University’s medical school today). Only recently were we finally able to find direct evidence that he was able to study in the College, even if he was not allowed to matriculate. Other breakthroughs were provided by Chris McKay, the talented archivist from the Schomburg Center whom we hired to help with our research. Chris was not only able to link David McDonogh with Frederick Douglass and the abolitionist networks in New York, but she also located a descendant of McDonogh, who received the posthumous medical degree awarded to McDonogh by Columbia University in 2018.

The story of the student who came to Lafayette with David, Washington McDonogh, ended quite differently, with him leaving for Liberia, which was the original plan for David. Fortunately, his guardian, also Walter Lowrie, was the head of the board of foreign missions for the Presbyterian Church, so all foreign correspondence came through him. We were able to find four or five other students who went to Liberia, along with the letters they wrote to Lowrie and the Presbyterian Church, thanks to this connection. As we continued researching, we kept discovering additional African American students who attended Lafayette, but of whom we had no record. We found that there were at least 12 students of color at the college during its first two decades.

Addressing the past

South College, Lafayette College.

Higher education has worked hard in recent years to document its involvement with slavery, with Georgetown University famously revealing that it sold slaves. These institutions have tried to figure out a way to make retribution, or at least to commemorate and make public these stories, through monuments or scholarships to the descendants of the slaves. Lafayette does not have the same stigma as some other institutions as it never owned slaves or profited from slavery, but its relationship to the subject is complex. Though the college admitted slaves, its motives were not strictly altruistic; the college was new and struggling financially, and not in a position to turn away money. Still, David McDonogh talks about his Lafayette education in glowing terms, even though it was fraught with discrimination. When David and Washington came to Lafayette in 1838, they were segregated in every area. Their classes were separate; they ate separately; they even lived in a separate building from the rest of the students. It was hard for David, a man with pride and ambition, to be treated that way. Interestingly, a couple of years later, a free Black student, who was also associated with John McDonogh, came to Lafayette and was treated more favorably, undoubtedly because he had never been enslaved.

Lafayette’s willingness to admit African Americans changed in 1847. A Black student requested admission in 1847 but was turned down; no other Black students were documented to have attended until 1947. I call it the “100-year gap.” I would tell alumni about it in presentations in the hope somebody would correct me, but no one ever did. Our students – particularly our Black students – often ask what happened. Again, it is worth remembering that our admission of those early students was not necessarily benevolent. Several of the college’s early presidents – all white, all male – were supporters of the American colonization movement, which aimed to send freed African Americans to Liberia as an alternative to emancipation in the United States.

Lafayette continued to have quotas on Black (and Jewish) students until 1958. By the late 1960s – a period of profound social change – there were enough Black students to start making demands and have those demands listened to. They asked for more Black students and faculty, more courses devoted to Black history, a Black house to host the Association of Black Collegians, and a commitment to anti-racism on campus. In response, the college stepped up recruitment of Black students, hired more Black faculty members, instituted a two-semester course called “The Black Man in America,” and gave the students their house. The only demand they didn’t – or couldn’t – meet was an end to racism on campus.

Forgotten no longer

Transcendence (2008), a sculpture by Melvin Edwards (b. 1943), honors David K. McDonogh, class of 1844, Lafayette College’s first African American graduate. Made of stainless steel, it stands 16 feet tall and weighs about four tons. Lafayette College Art Collection.

An academic institution is supposed to be committed to the truth. The discovery of David and Washington McDonogh’s story has been markedly influential at Lafayette College. This new connection to our past has offered numerous opportunities for pedagogy and opened doors to alumni outreach. For our current students, it has been incredibly meaningful to be able to see the history of those who came before them. One of the things we always wanted so desperately is a photograph but that has yet to appear. We remain hopeful though, as David was a prominent physician and lived during a time when photography was common. Fortunately, he is remembered in other ways.

In 2005, Daniel Weiss – now President and CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art – became the president of Lafayette College. Weiss mentioned McDonogh in his inauguration speech. He touched on his story only briefly, but it was enough to catch the attention of Curlee Raven Holton, Professor of Art, who successfully sought to have the College commission a sculpture in McDonogh’s memory. The resulting artwork, Transcendence (2008), by the distinguished African American artist, Melvin Edwards, himself descended from slaves from Louisiana and Mississippi, is a monumental abstract piece, incorporating broken chains.

Lafayette has also created an exhibition about the McDonogh story and its early Black students on campus in the College’s largest classroom building. The exhibit traces the journeys of David and Washington from New Orleans to Lafayette College to New York and Liberia. Images include the manifest of the ship that brought the young men north, listing them both as chattel, as well as a photograph of the huge crowd gathered in New York City for the ground-breaking of a second McDonough (sic) Memorial Hospital in 1917, named in honor of David, which was never built. The exhibition ends with a walkway of silhouettes of Lafayette College’s early Black students with their biographies. Ironically, it is now two silhouettes short, as new students have recently been discovered. And it is entirely possible that there may be more.

Diane Windham Shaw is Director Emerita of Special Collections and College Archives at Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania, USA.

Ophthalmology in America: Black and White

For too long, artificial barriers have kept Blacks out of medicine. It is time to dismantle racist hierarchies – the David Kearney McDonogh Scholarship is only the beginning.

By Daniel Laroche

Daniel Laroche first learned of David Kearney McDonogh from Richard Koplin in 2015. He decided to memorialize McDonogh’s legacy through a creative scholarship, with the hope of sharing his story with the next generation of medical students, ophthalmologists, as well as the wider African American community and the rest of America. Working in partnership with the National Medical Fellowship, Laroche and nine other ophthalmology colleagues chipped in $500 to form the first $5,000 scholarship for African American, Afro Latino and Native American students – three of the most severely underrepresented groups in medicine. “We wanted McDonogh’s legacy to inspire students to pursue ophthalmology with academic excellence, research, innovation and leadership” says Laroche. “We are now able to endow the scholarship every year and I recently commissioned a portrait of McDonogh, which we donated to New York Eye and Ear’s Infirmary of Mount Sinai’s patient waiting area, so even more people could know his story.”

Even in 2021, we are a long way from achieving equality in medicine. The number of Black ophthalmologists in the United States has remained unchanged since the 1970s – why is that? In part, the problem lies in the standardized testing used to screen applicants. These tests have cultural biases that discriminate against Black students – students who are otherwise highly qualified with grades and research. These screening criteria have absolutely no correlation with how good an ophthalmologist or surgeon someone will become – and have discouraged applicants from choosing our specialty for decades. Standardized testing strongly correlated with wealth and class. Interestingly, the test does not add points for speaking a second language fluently, an incredibly valuable skill for a doctor in today’s America. It seems unfair that applicants can be penalised for not coming in the top tenth percentile of a test, but not rewarded for being able to communicate with a patient in their mother tongue. These are just a few of the biases we continue to fight against. Fortunately, the board is replacing the existing system with a pass/fail examination. The same problems exist at the high school and college level leading to significant disparities in the pipeline. Magnet high schools and colleges should accept the best students from various communities across America to truly reflect the fabric of America.

We are making progress in other areas too. The American Academy of Ophthalmology subsequently launched a Minority Ophthalmology Mentoring (MOM) Program. The National Medical Association has had a long history of addressing health disparities since its inception in 1895, both by strengthening the pipeline for students from underrepresented backgrounds and more recently, with the Rabb Venable Ophthalmology research competition. The David Kearny McDonogh Ophthalmology/ENT Scholarship also provides additional opportunities for mentoring, guidance and encouragement to students so they continue to follow their passion. If there are any perceived weaknesses, these can be strengthened with additional resources and exposure to the profession. These students are incredibly bright, and the fact that they did not score in the top percentile of the class does not mean that they won’t make great surgeons. We need to remove artificial barriers that have been instrumental in keeping Black students out of ophthalmology.

Daniel Laroche

I also was discouraged from applying ophthalmology, I was told to consider another speciality. But I have a very determined personality and once I set my mind on something, I do it no matter what. I even took an additional year off between my third and fourth years of training to do clinical research and graduated with honors from Cornell University Medical College. It was very competitive but it allowed me to immerse myself more fully in the field of ophthalmology and publish my own research. That extra year made me a super-strong candidate, more so than my contemporaries. But I could only do that by standing on the shoulders of those who have gone before me, including David Kearny McDonogh.

McDonogh was not the only person who has been written out of history. Unfortunately, global white supremacy has distorted our understanding of the past. Did you know that the first ophthalmologist was an African named Iry in 2,500 BC? These stories should be celebrated. I like to think that if people were taught a broader view of history, we would all have a greater respect for different cultures – particularly African cultures, which have had the origin of culture, spirituality, science, and medicine, for thousands of years.

We've made a tremendous amount of progress in America but there are some who want to turn the clock back. The recent attack on the Capitol, where the Confederate flag was flown, did not even occur during the American Civil War. This remains a deadly reminder that right-wing groups are attempting to re-establish white supremacy.

We all want to live in peace, be successful, raise our families and have a good life and provide great health care to the community. It is only when you introduce artificial barriers of racial supremacy (sociopathy) that there is discord. I am hopeful that things will improve with proper information, truth, and education.

Sharing stories (modern and historical) is a critical part of repairing past wrongs – but we cannot progress without support from everyone in healthcare, including industry. Pharma companies make millions of dollars globally from the Black community in America, the Caribbean, and Africa, from equipment and drugs to pharmaceuticals and surgical supplies. But, unfortunately, there is a lack of diversity at the leadership level in these companies. To have excellent health outcomes globally, you need a diverse global cultural leadership. The industry needs to recruit talented people from diverse backgrounds and show financial commitment by investing in pipeline training programs and scholarships to support the next generation of Black ophthalmologists and medical and pharmaceutical industry leaders. Large hospitals would also do well to invest a good portion of their budget towards inclusive educational pathways and leadership diversity.

Change is happening but it is far too slow. We need pressure from people in all industries – and not just people like me. Look at your leadership; does it reflect the diversity of your community, the country, the world? We all have a role to play when it comes to proposing solutions to these problems. For many years, the doors to ophthalmology were closed to underrepresented minorities; now they are opening, let’s keep it that way. We have to remember it should not be about the white and black but about one race – the human race.

Daniel Laroche is the Director of Glaucoma Services and President of Advanced Eyecare of New York and Clinical Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology at The New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, New York, USA.

Representation Matters

If we want a more diverse subspecialty, we need to level the playing field

By Jacqueline Busingye

Jacqueline Busingye

Of the 20,000 ophthalmologists in the US, approximately 400 are Black or of African American descent. This is a huge problem, and not just because patients are proven to respond differently to clinicians they connect with on some level. The truth is you cannot be what you cannot see. Ophthalmology has a diversity issue in terms of race, but also gender – especially within academic leadership. People often make the case that there are more women residents than there are men (at 51 percent to 49 percent), but as you climb up that academic ladder, the number of women falls off rapidly. Of that 51 percent, only a small number make it to associate professor, a fraction of that to full professor, and even fewer to department chairs.

Ophthalmology has traditionally been a very insular specialty, with practices handed down within families and mostly from fathers to sons. There are some institutions that will not interview you unless one of your parents previously attended or you have a strong association with someone connected to the program. Knowing this, how can a strong unconnected applicant ever break in?

The lack of exposure is another major hindrance to entry into ophthalmology as it is not traditionally a core rotation, so students have to opt in – problematic if they don’t even know what the specialty is. Even if students do choose to do an ophthalmology rotation, not all medical schools have a program so they have to travel to another institution willing to host them. Without mentorship to guide them, offer recommendations with setting up rotations or encourage them through the process, it’s very difficult to reach students who may otherwise have a limited or non-existent knowledge of the specialty.

This is where we come in. The David K. McDonogh scholarship fund was spearheaded by Daniel Laroche as a way to not only share McDonogh’s story, but to bring more underrepresented individuals into the spheres of ophthalmology and otolaryngology. When I walked into our first group meeting, I saw six other Black extremely accomplished clinicians and realized that I had never been in a room with that many ophthalmologists that looked like me. For me, already an attending, this was inspiring so I could only imagine the potential good that would be accomplished for the medical students we set out to help.

David K. McDonogh was an enslaved man born in 1821 who, through sheer hard work and determination, became the first African-American physician in ophthalmology/ENT in New York. He is the inspiration for the work our organization does to mentor students through our vast network and help guide them as they apply, and eventually matriculate, into and ophthalmology or ENT residency. Those who do receive the scholarship are given a financial gift that they can use to help cover costs associated with the applications process, be it registration or travel. As many have told us, this has allowed them to take advantage of opportunities they otherwise would have needed to take out loans for or missed altogether.

Initially, the program was focused solely on mentoring and aiding with scholarships to medical students in the Tri-State area but as we raised more money, we were able to open the scholarship to students nationally. Our applicants are incredibly accomplished in their own right, all they need is a little support to get into these subspecialized areas.

I can honestly say that our program applicants and many of the medical students I teach are much more accomplished and qualified than I ever was at their stage of training. If they are not getting chosen for residencies, I don’t think it’s for lack of accomplishment but most likely lack of mentorship to help them put forth the best application possible. That is the gap we, as part of the David K. McDonough committee, are trying to fill.

Going forward our plan is to grow our network, mentorship and the number of scholarships we are able to give. Thanks to our scholarship efforts we have managed to fund at least one scholarship in perpetuity. As word of our scholarship fund and network grows, we hope to catch students in their first year rather than their fourth so that they are being mentored from the beginning and gaining experiences – both clinical and research – so that they can be better applicants and also make more informed decisions about their future in medicine. If students don’t choose to go into a profession – whether they are in a minority group or not – it should be because they are not interested in it, not because they don’t know it exists.

Jacqueline Busingye is a founding member of the David K. McDonogh Scholarship Fund, Chief of Ophthalmology at Albany Stratton VA, and Associate Professor of Ophthalmology at Albany Medical College, New York, USA.