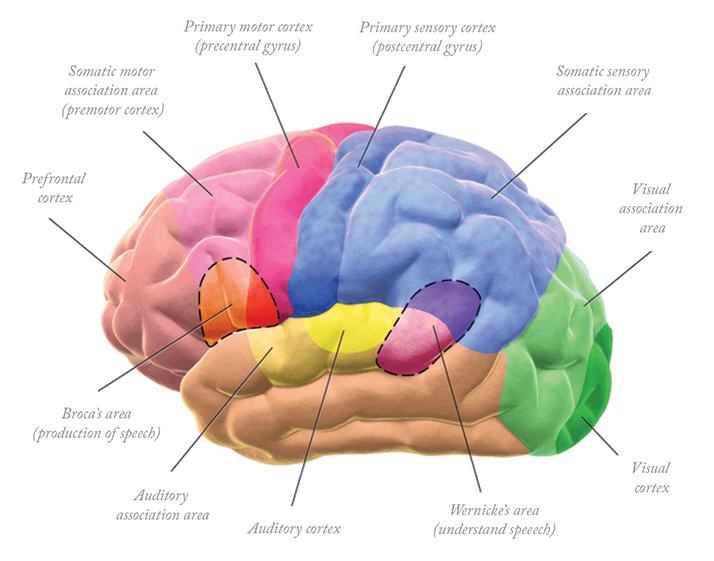

It’s sometimes said that you don’t see with your eyes, you see with your brain. The site where most sensory processing occurs in the brain is the cerebral cortex, with distinct regions being devoted to certain specialized functions – the visual cortex processes only visual input, the auditory cortex only processes the signals coming from the cochlear nerve and so on (see Figure). Or so it was thought. A team of researchers from Glasgow University in Scotland have shown that the visual cortex processes information from the ears as well as the eyes (1).

The team used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) as a marker of visual cortex activity, with the images being passed through a special algorithm that identifies unique brain activity patterns. Ten subjects were blindfolded and, in an initial experiment, played audio of three types of natural sound: birds singing, traffic noise, and a talking crowd. Results from the algorithmic analysis of the visual cortex fMRI data not only demonstrated that there was activity in the visual cortex during the sounds, but that the activity was sufficiently different for the research team to distinguish between each of the three sounds. In a second experiment, the subjects, now in the absence of sight or sound, were asked to just imagine the same sounds as before. This revealed that even imaginary audio can evoke activity in the visual cortex – and again the originating sounds could be decoded from the fMRI output.

The study authors suggest that auditory input enables the visual system to predict incoming information and could confer a survival advantage. “Sounds create visual imagery, mental images, and automatic projections,” says Lars Muckli, who led the research. “So, for example, if you are in a street and you hear the sound of an approaching motorbike, you expect to see a motorbike coming around the corner. If it turned out to be a horse, you’d be very surprised.” The research has potential therapeutic implications too, according to Muckli. “This might provide insights into mental health conditions such as schizophrenia or autism and help us understand how sensory perceptions differ in these individuals,” he suggests.

References

- P. Vetter, F.W. Smith, L. Muckli, “Decoding Sound and Imagery Content in Early Visual Cortex”, Curr. Biol. pii: S0960-9822(14)00458-8 (2014). doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.04.020.