- Is there a link between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG)? Smaller, prospective studies tend to suggest yes, but larger retrospective cohort studies disagree

- A recent record linkage study – involving over 67,000 patients with OSA – has revealed no association

- However, OSA and AMD were found to be positively associated, and this association was identified to be independent of obesity

- This represents a new area of interest for vision researchers, and may have important implications for clinical practice in the future

Rising obesity levels in the general population have meant that obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) – a condition where the upper airway repeatedly collapses during sleep – is now a common disorder of the adult population. People with OSA suffer disrupted sleep, as repeated interruptions to their breathing results in neurological arousal and reduced blood oxygen saturation. Unsurprisingly, recurrent episodes of hypoxia over time can have an impact on health, including increased risk of cardiovascular disease, metabolic impairment and stroke (1). Over recent years, many have considered that there may be a link between OSA and primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), rationalized by the following hypotheses:

- Recurrent episodes of hypoxia are associated with reduced optic nerve head perfusion

- OSA-induced hypoxia leads to an increased risk or progression in glaucomatous optic neuropathy, plus

- Mechanical factors affectingintraocular pressure (IOP) may also be involved.

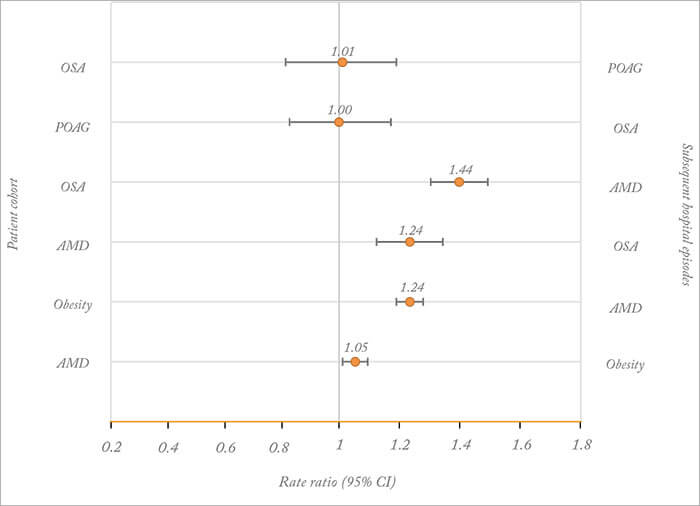

If a link was established, this would provide important insights into POAG pathophysiology, particularly the contribution of vascular dysfunction, and a strong rationale for screening individuals with one condition for the other. The problem is that it isn’t clear whether OSA and POAG are linked, as previous studies have reported conflicting results: smaller prospective studies tend to report an association, whereas larger retrospective cohort studies tend to find no such association (2). When you look closer, many of these studies had significant methodological limitations in terms of sample size and study design. Isn’t it time that someone provided some strong data? That is exactly what Michael Goldacre and his collaborators (Tiarnan Keenan and Raph Goldacre) have delivered in their recently published paper – although the results may not be entirely as anticipated by some (3). In a cohort of over 67,000 patients with OSA – collated from linked English hospital episode statistics (1999–2011) – they observed that there was no significant increase in the risk of POAG when compared with a reference cohort (containing over 2,600,000 people; Figure 1).

For completeness, there was also no significant risk of OSA in a cohort of over 87,000 patients with POAG. Not only did they observe that OSA and POAG were not positively associated in these cohorts, the closeness of the rate ratios to one suggested little, if any, association, even when subgroups such as sex and age groups were analyzed. Interestingly, they also observed that OSA was significantly associated with POAG in the first year of admission but not in subsequent years, suggesting that additional cases of sleep apnea may have been diagnosed in the short-term at the point of POAG diagnosis (presumably from referral by ophthalmologists). Some would argue that Goldacre and his collaborators have presented strong evidence that it may be time for ophthalmologists to consider putting the hypothesis of a link between POAG and OSA to bed. Moving on from POAG, Goldacre and his collaborators also identified a novel association between OSA and age-related macular degeneration (AMD; Figure 1), and this significantly increased risk was also observed when the OSA cohort was analyzed by sex and age. They also analyzed an obesity cohort – aware of the knowledge that obesity has been identified as a risk factor for both OSA and AMD – and revealed that the relationship between obesity and AMD was not as strong as the observed association between OSA and AMD, indicating that OSA had a significantly independent effect. But what does this all mean? We spoke with Tiarnan Keenan – the corresponding author for the study – for his thoughts on the findings and where the field may be headed.

References

- C Gonzaga et al., “Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases”, J Hum Hypertens, 29, 705–712 (2015). PMID: 25761667. AA Aref., “What happens to glaucoma patients during sleep?”, Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 24, 162–166 (2013). PMID: 23262987. TD Keenan et al., “Associations between obstructive sleep apnoea, primary open angle glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration: record linkage study”, Br J Ophthalmol. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 27044342. BL Nesmith et al., “Poor responders to bevacizumab pharmacotherapy in age-related macular degeneration and in diabetic macular edema demonstrate increased risk for obstructive sleep apnea”, Retina, 34, 2423–2430 (2014). PMID: 25062438. TD Keenan et al., “Associations between age-related macular degeneration, Alzheimer disease, and dementia: record linkage study of hospital admissions”, JAMA Ophthalmol, 132, 63–68 (2014). PMID: 24232933. TD Keenan et al., “Associations between age-related macular degeneration, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: record linkage study”, Retina, 35, 2613–2618 (2015). PMID: 25996429.