- Cataract surgery in patients with herpetic disease can pose unique challenges but, with the right planning, you can achieve great results

- Before surgery, you need to identify a “quiet window”, get your readings, and decide upon the appropriate surgical approach. It’s also important to pick the right IOL

- During surgery, be sure to protect the surface of the eye, beware of floppy irides, and consider using Trypan blue for better visualization in cloudy corneas

- When it comes to follow-up, medication management is key; be aware of the medications your patient was on before surgery, and plan accordingly

Cornea specialists encounter many patients with herpetic disease – and these patients can pose unique problems when it comes to performing cataract surgery. However, with the right planning and management, you can achieve the best outcome for the patient. I like to break my own management into three stages: preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative considerations.

Before

For epithelial disease, my preference is that patients have been quiet and stable for six months at a minimum. However, for chronic uveitis, this may be difficult to achieve – so there may be only small windows of quiescence (and limited opportunity to proceed). In fact, many of these patients are being co-managed with retina/uveitis specialists; if the view of the fundus is limited by the cataract, I often need to proceed whenever a quiet window occurs in these patients, breaking my own six month rule. The first step is to make sure you have a stable surface – just as we do with any cataract patient, particularly ones who have surface disease and dry eye. You need to optimize the tear film and ensure that the surface is as good as it can be – some of these patients may also benefit from a punctal plug.Do I have confidence in my IOL calculations?

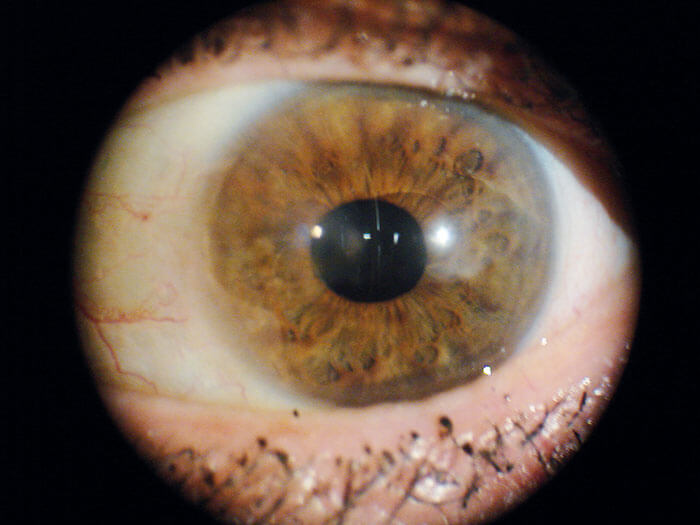

Many of these patients will have corneal scarring, which can cause a number of further problems, such as inaccurate keratometry (K) readings, which in turn leads to inaccurate IOL calculations. Corneal scarring can also lead to postoperative aberrations and visual disturbances, even if you choose the correct lens. The solution is to firstly get the cornea cleaned up as best you can, being sure to manage the tear film. Next, get multiple sets of K readings (including manual ones). I look at corneal topography, IOL Master readings, and manual K readings. If these all look consistent, I’m usually comfortable to proceed. But what can be done if you can’t get good readings? It may help to compare with the other eye – or older records, if you have any prior to the onset of corneal disease. Occasionally, an amniotic graft membrane may be needed to improve the surface enough to obtain accurate measurements.Which IOL?

I’m particularly hesitant to use multifocal lenses in a scarred cornea, and a good general rule for these patients is to use premium lenses with caution. An accommodative lens is an option, as you are likely to encounter fewer problems with aberrations – but if there is any concern over the accuracy of the IOL predictions, I’d also be hesitant to use an accommodative IOL. Though they can work well from an aberration standpoint, there is still a risk of an unhappy patient if they are a diopter or half a diopter off-target. For the most part, I prefer a monofocal lens for these patients. When it comes to astigmatism, success can be found with arcuate incisions made using a femtosecond laser. But it’s important to remember that, if a patient has a lot of astigmatism and you use a toric lens, you may not be able to use a scleral contact lens postoperatively – and that means you could run into a problem that you are unable to fully correct.During

Once you go into surgery, it’s important to protect the surface of the eye – it’s going to be very vulnerable, so you need to ensure that you keep it well lubricated. You may have issues with visibility, so I would recommend using Trypan blue. Normally, we think of using Trypan blue when we have a white cataract, but I’ve found that it also helps improve contrast in some patients with a cloudy cornea. Another tip is to use your surgical microscope’s ability to change illumination on-the-fly, if that’s an option. My microscope can change from on-axis to off-axis illumination, and I frequently play around with the settings to give me the best background illumination to visualize the capsulorhexis. With my old microscope, I sometimes used to switch the illumination off completely and instead use the vitrectomy light pipe, held from the side, to give a nice reflex illumination of the capsular bag. The lesson is: don’t be afraid to play with the illumination, as doing so can help you complete the capsulotomy. Such patients also have a tendency to suffer iris atrophy and will often present with similar characteristics to those seen with floppy iris syndrome (such as patients who have been prescribed Flomax). In these cases, use your favorite technique for floppy irises, whether that’s a Malyugin Ring, iris hooks, Omidria, or something else.After...

Postoperatively, I use my standard course of medication: an antibiotic and a non-steroidal drop. For steroids, I taper very slowly, usually starting at QID and staying there for two weeks. Then, I’ll taper down weekly: three times per day for one week, then two times per day for one week, and so on. Notably, if the patient was on a steroid before I operated, I won’t go below their preoperative medication level – I’ll stay there indefinitely. I believe one of the most common causes of postoperative flare-ups is caused by doctors cycling through their normal routine and forgetting that their patient was on a drop before the operation. And if the patient is being co-managed by an optometrist, who wasn’t aware of their existing medications, they may also taper off the drops.For the antiviral drug regimen, I usually recommend acyclovir four times a day for about three weeks. When I start tapering the steroids, I cut the acyclovir down to twice a day, until they’re finished with the steroids, and then the regimen ends. But again, if they were on acyclovir preoperatively, I keep them on their previous dose. Remember: it’s important to continue to monitor these patients’ herpetic disease not just during the postoperative period, but long afterwards too. Finally, if vision isn’t where you want it to be, you need to continue treating their tear film. Often, I’ll use a scleral contact lens to see how much more I can improve vision, and this generally works very well. In short, herpetic disease does not have to be a barrier to good postoperative vision. Kenneth Beckman is Director of Corneal Surgery at Comprehensive Eyecare of Central Ohio, and a clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at Ohio State University. The author reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.