COVID-19 has left no aspect of modern life untouched; its impact unprecedented and ongoing. Public health measures have been imposed globally to reduce the scale of the outbreak – including home working and schooling, as well as widespread use of face masks. But beyond containing the virus, these measures have had a second, unexpected consequence for patients with existing ocular problems: increased prevalence of dry eye disease (DED), and worsening of DED symptoms.

There are three arguments as to why. The first is that home confinement and working remotely have inevitably led to increased screen time – a shift which has had a significant impact on eye health and DED in particular. Studies have shown the average number of blinks decreases from around 18 per minute in normal conditions to three or four per minute while looking at a screen (1). These blinks are not as forceful or complete as those done under normal conditions. This combination of reduced frequency and intensity of blinks increases the risk of inducing or exacerbating DED (1). Low humidity and restricted airflow indoors are also presumed to induce or exacerbate DED, causing a higher evaporation of tears from the ocular surface, which may in turn lead to more flare ups of the condition (2).

The second potential reason for the proliferation of DED in the COVID-19 era is the mass use of face masks. It has been proposed that the wearing of, displacement or incorrect fitting of a mask could disperse air around the eyes, causing a rapid evaporation of tears (3, 4).

The third and final reason for an increase in ocular surface problems is practical. The lockdown has prevented many patients from receiving regular eye check-ups, limiting their access to treatment for dry eye and other ophthalmic conditions. Remote monitoring can be as difficult for patients as it is for physicians, as they struggle to deliver effective and long-lasting dry eye symptom relief to the surface of the eye.

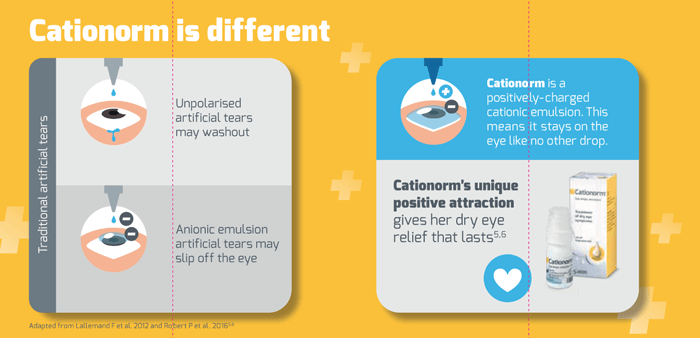

But the potential solution could be simple: Cationorm. Where unpolarized artificial tears may wash out and anionic emulsions may “slip off” the eye, Cationorm’s unique positively charged cationic emulsion stays on the eye like no other drop (5), offering dry eye relief that lasts.

This hydrating and lubricating drop has been specifically formulated with the needs of dry eye sufferers in mind, particularly women over the age of 45 with additional risk factors – whether they are taking chronic medications which have a drying effect, wear contact lenses regularly, or have underlying comorbidities which cause or exacerbate DED, this patient population can have an increased risk of disease progression in the COVID-19 pandemic. Why? Women on chronic medication such as hormone replacement therapy (HRT) are more likely to progress to severe dry eye (6). Although the role of estrogen in dry eye is unclear, it puts women at a 69 percent higher risk of dry eye – a figure that increases by 15 percent every three years (7).

Contact lenses have been found to make the tear film thinner, resulting in a patchy lipid layer with poor wettability and increased tear evaporation rate (8), with up to 75 percent of contact lens wearers reporting symptoms of ocular irritation (9).

The stats are even more damning for patients with Graves’ disease: research suggests that at least 50 percent suffer from dry eye (10), as exophthalmos makes it difficult to close the eyes, resulting in inadequate lubrication (11). Many other comorbid conditions also create and exacerabate DED.

For patients seeking your help for DED and who are finding their condition worsening, think Cationorm. Cationorm’s unique positively charged cationic emulsion stays on the eye like no other drop, providing long-lasting relief of DED symptoms. Whatever the condition, Cationorm provides optimum hydration and increased comfort.

References

- S Patel et al. “Effect of visual display unit use on blink rate and tear stability,” Optom Vis Sci, 68, 888 (1991). PMID: 1766652.

- S Koh et al., “Effect of airflow exposure on the tear meniscus,” J Ophthalmol (2012). PMID: 22570766.

- M Moshirfar et al., “Face mask-associated ocular irritation and dryness,” Ophthalmol Ther, 9, 397 (2020). PMID: 32671665.

- G Giannaccare et al., “Dry eye in the COVID-19 era: how the measures for controlling pandemic might harm ocular surface,” Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2020), [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 32561978.

- F Lallemand et al., “Successfully improving ocular drug delivery using the cationic nanoemulsion, novasorb,” J Drug Deliv (2012). PMID: 22506123.

- C Matossian et al., “Dry eye disease: consideration for women’s health,” J Womens Health (Larchmt), 28, 502 (2019). PMID: 30694724.

- DA Schaumberg et al., “Hormone replacement therapy and dry eye syndrome,” JAMA, 286, 2114 (2001). PMID: 11694152.

- JAP Gomes et al., “TFOS DEWS II iatrogenic report,” Ocul Surf, 15, 511 (2017). PMID: 28736341.

- K Dumbleton et al., “The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: report of the subcommittee on epidemiology,” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 54 (2013). PMID: 24058130.

- C Gürdal et al., “Ocular surface and dry eye in Graves’ disease,” Curr Eye Res, 36, 8 (2011). PMID: 21174592.

- RS Bahn, “Graves’ ophthalmopathy,” N Engl J Med, 362, 726 (2010). PMID: 20181974.