Diabetic macular edema (DME) may occur when blood vessels leak contents into the macular region. The symptoms of the condition are blurring or vision distortion and, in about 10 percent of diabetic patients, vision loss. Management has traditionally consisted of focal/grid macular laser, according to the guidelines established by the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study. More recent prospective clinical trials examining the effect of intravitreal ranibizumab in the treatment of DME (READ-2 (1), RESOLVE (2), RESTORE (3), and DRCR.net protocol I (4)) have demonstrated improvement in vision. Similar treatment benefits have also been noted in clinical trials evaluating intravitreal bevacizumab and aflibercept (BOLT (5) and da Vinci (6), respectively).

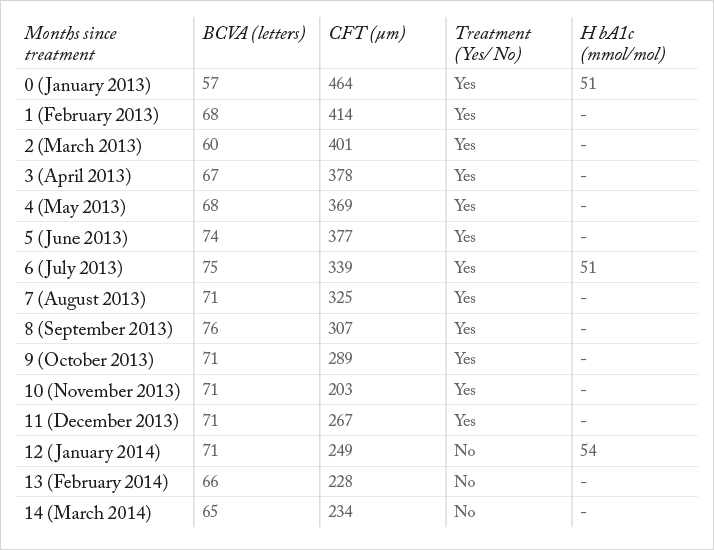

Case presentation Based on the aforementioned evidence, we report our experience with a patient with a long-lasting refractory DME in the right eye (RE) resistant to previous treatments, who underwent intravitreal ranibizumab injections. The patient was a 60-year-old man referred to our department because of deteriorating visual acuity in the RE. Regarding the ophthalmological history, he had been diagnosed with background diabetic retinopathy and a recurrent DME in the RE since 2001. He had previously been treated with macular grid laser, intravitreal bevacizumab (six injections over a period of two years) and choline fenofibrate. The systemic history revealed type 2 diabetes mellitus (15 years), hypertension (20 years), hyperlipidemia (15 years) and anemia (15 years), which were all under good control. Ophthalmological examination revealed the following: background diabetic retinopathy with DME, intraretinal fluid on optical coherence tomography (OCT) involving the fovea, increased central foveal thickness (CFT) of 467 μm, reduced best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) to 57 letters, media clarity, intraocular pressure (IOP) of 18 mmHg and cup-to-disc ratio of 0.3. Management and outcome Since the DME was involving the fovea, the patient was not eligible for macular laser. Also, the edema showed recurrence, despite previous treatment with intravitreal bevacizumab injections. After we discussed the risks and benefits of intravitreal ranibizumab injections with the patient, he decided to proceed. Pretreatment biochemistry, electrolyte and hematology tests were within normal limits, as was urinalysis. The patient underwent BCVA estimation, IOP measurement, OCT, biomicroscopy and indirect ophthalmoscopy prior to treatment and at every follow-up visit. In addition, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured every six months during the treatment period. The treatment consisted of an intravitreal ranibizumab injection every month for a period of one year from January to December 2013. The treatment plan and the main outcomes are shown in Table 1. There was no evidence of treatment-related adverse events.

Discussion As can be seen from the results presented in Table 1, the patient presented a gradual reduction of CFT associated with improvement in BCVA. BCVA improved within the first month of treatment and remained stable during the 5-12 month treatment period. After completion of treatment, BCVA was slightly reduced. This reduction of BCVA in the last two months of follow-up shows tendency to DME recurrence, although it was not followed by a significant change in CFT. However, given the higher likelihood of potential risks associated with frequent use of intravitreal ranibizumab injections, in cases like this we would recommend exploring other treatment options, such as the fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant (Iluvien). Approved in several European countries for the treatment of chronic DME, Iluvien appears to be more efficacious than other treatments in improving visual acuity, even three years after treatment; reducing the number of injections needed. Notwithstanding this, cataract and steroid-induced glaucoma are known risks associated with the use of intravitreal steroid injections. Cataract can, however, be addressed by surgery if its effect on vision is significant. In patients who have normal IOP and no family history of glaucoma, Iluvien could be considered as a safe alternative. Conclusion This case presentation revealed that the use of intravitreal ranibizumab injections on a monthly basis can be effective for the stabilization of diabetic maculopathy. However, this is an example of chronic DME where edema recurs upon cessation of anti-VEGF treatment for DME with corresponding loss of vision. In such cases where edema persists after multiple anti-VEGF treatments, Iluvien provides an important therapeutic option. Statement: A written informed consent was provided by the participant

Read the next case report

References

- D.V. Do, Q.D. Nguyen, A.A. Khwaja, et al., “READ-2 Study Group. Ranibizumab for edema of the macula in diabetes study: 3-year outcomes and the need for prolonged frequent treatment”, JAMA Ophthalmol. 131(2), 139–145 (2013). P. Massin, F. Bandello, J.G. Garweg, et al., “Safety and efficacy of ranibizumab in diabetic macular edema (RESOLVE Study): a 12-month, randomized, controlled, double-masked, multicenter phase II study”, Diab. Care. 33(11), 2399–2405 (2010). U. Schmidt-Erfurth, G.E. Lang, F.G. Holz, et al., “The RESTORE extension study group. Three-Year Outcomes of Individualized Ranibizumab Treatment in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema: The RESTORE Extension Study”, Ophthalmol. S0161–6420(13)01167-6 (2014). Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net), R.W. Beck, A.R. Edwards, L.P. Aiello, et al., “ Three-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing focal/grid photocoagulation and intravitreal triamcinolone for diabetic macular edema”, Arch. Ophthalmol. 127(3), 245–251 (2009). S. Sivaprasad, R. Crosby-Nwaobi, L.Z. Heng, et al., “Injection frequency and response to bevacizumab monotherapy for diabetic macular oedema (BOLT Report 5)”, Br. J. Ophthalmol. 97(9), 1177-1180 (2013). D.V. Do, Q.D. Nguyen, D. Boyer, et al., “One-year outcomes of the da Vinci Study of VEGF Trap-Eye in eyes with diabetic macular edema”, Ophthalmol., 119(8), 1658–1665 (2012).