- What do patients with glaucoma see? The ubiquitous “tunnel vision” images seen so often in awareness campaigns actively mislead

- Because the brain “fills in the gaps” in regions of vision loss, patients can be unaware that their disease is progressing (as they don’t have tunnel vision) until their disease has reached an advanced stage

- Current testing practices in the UK are such that some people with glaucoma go undetected, whereas others are over-tested.

- More research into how clinical measurements relate to level of visual impairment in patients, and awareness of the subtle changes in vision, are important areas for improvement

Glaucoma remains something of a mystery. Despite having a number of tools at our disposal – the tonometer, perimeter, slit lamp, goniolens and optical coherence tomography – we still only have one card to play: the modification of intraocular pressure (IOP). Fortunately, the topical IOP-lowering drugs and the surgical interventions we do have available mean that only around five percent of patients are at risk of a serious visual impairment. But screening and timely intervention is crucial – once vision has been lost, there’s no way to get it back. But what do patients understand of this disease? How much vision has to be lost before the impact on their daily life becomes “serious”? It turns out that despite all of the tools we have available to measure the visual function these patients, our understanding of how visual field defects in glaucoma relate to a patient’s ability to perform their day-to-day activities (and therefore their quality of life) remains inadequate. But in some ways, the question boils down to a very simple question: what, exactly, do patients with glaucoma see?

Tunnel vision

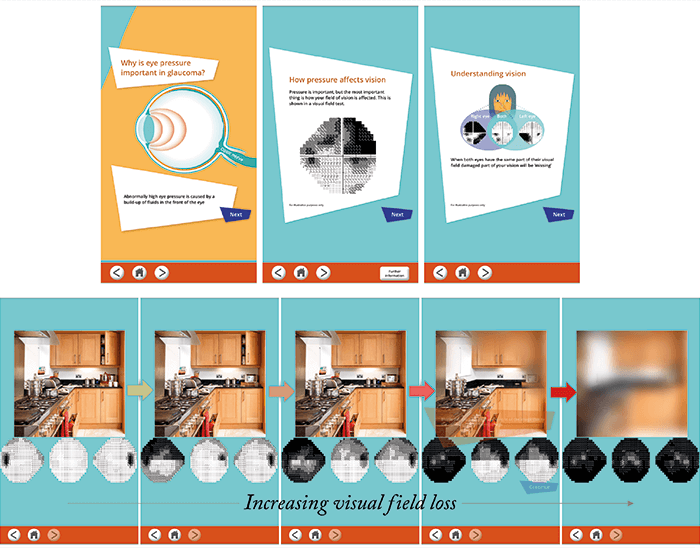

Patients like to consult Doctor Google in order to understand the disease a real doctor diagnosed them with. Most of the time they’ll read that glaucoma affects peripheral vision, and this statement is most often accompanied by the near-ubiquitous “tunnel vision” image (Figure 1) that’s intended to show people what their vision would look like if they had glaucoma. There’s just one problem – it’s a gross misrepresentation of what people with glaucoma actually see (1). A growing body of evidence is showing that in patients with symptomatic vision loss, the changes are far more subtle than a tunnel of good vision in the center with blackness surrounding it. The reason that these images are so wrong is that they fail to take account of the fact that people ultimately “see” with their brains – and the brain interprets and fills in the gaps – for example, nobody is aware of their blind spot. The brain extrapolates and fills in the gap, and this is why people often don’t notice the true extent of their vision loss until quite late along the process. My problem with these misleading “tunnel vision” depictions of vision loss in glaucoma is this. Many patients will see these images and believe that this is what “serious” glaucoma looks like; they’ll think “I haven’t got this tunnel effect, so my glaucoma’s not too bad! Maybe I don’t need to take my eyedrops” – or not worry when they miss a few days of treatment. The drugs do work – so long as their treatment regimen is adhered to. The problem is that if you’re diagnosed with a condition where you have to instill eyedrops multiple times a day for the rest of your life, it’s going to be a challenge – especially as you’re taking a treatment for vision loss, but you don’t feel like you’ve lost any vision yet! The message that eyedrop regimen adherence is important can be undermined when patients see these simplistic and misleading depictions of glaucoma-impaired vision.The other big problem is glaucoma awareness. It’s one of the most prevalent age-related eye diseases, and in a world with an increasingly aging demographic, glaucoma prevalence is just going to continue to rise for the foreseeable future. But in awareness campaigns, we once again see the “black tunnel” – how frustrating! How can we raise awareness of a disease that causes subtle changes in vision – often almost unnoticeable changes – while simultaneously displaying this image depicting an incredibly noticeable disappearance of peripheral vision? But things are slowly improving. It appears that people are starting to become a bit more creative in the way they depict the vision loss associated with glaucoma, and this is very pleasing. My colleagues and I have also created an app to help communicate the symptoms of glaucoma and what patients can realistically expect to see as their disease advances (see “Putting Glaucoma Into Perspective” below).

- An interactive app developed by the Crabb Lab at City University London

- Educates patients and their family on the disease, the importance of proper eyedrop use, and a demonstration of the subtle visual changes glaucoma can cause – with not a “tunnel” in sight

On balance

A better understanding of vision loss in glaucoma could also improve our understanding of how the disease impacts daily life. Patterns of vision loss can vary hugely from person to person, even in cases considered equally severe or otherwise comparable. Some people may see much more of an impact, depending on the location of the vision loss. For example, we’ve performed tests on reading, face recognition and searching for objects, and sometimes patients’ performance on these visual tasks is not very closely related to the measurements taken in the clinic. What this means is that we will have patients with equivalent visual function test results, but their ability to cope with daily life – which translates into their quality of life – will vary from one person to another. It’s important to spot those who are struggling; for example, those with inferior visual field loss have been shown to have more problems with mobility, and will be at a higher risk of falling than patients with superior visual field defects (2)(3)(4). But not all patients get frequent visual field tests as part of their management, and some low-risk patients can be managed purely on IOP alone. If performed, these tests can give patients greater insight into their condition – as long as they are told the results. From speaking with patients, I can say that it’s a test that fills patients with great anxiety, and some may struggle with it because of this. But not all ophthalmologists communicate results well with their patients (5) – I think that these results should be shared with and explained to patients, to help them understand the topography of their own vision loss, and how it might affect them.Testing times

I think the way clinicians approach glaucoma could also be improved. Often, the focus is on ever more precise measurements and earlier diagnoses, but here in the UK at least, there are much simpler steps that could be taken to improve the patient experience. For one, I think our service delivery for glaucoma could be improved – a standard sight test for someone aged over 40 years doesn’t necessarily incorporate all the tests you need to accurately spot glaucoma. Conversely, in those patients diagnosed with glaucoma, there’s a lot of over-testing. Many patients visit the eye clinic every four or six months, but this is done both for patients who are showing little change, and for those who are deteriorating rapidly. Stratifying patients into groups based on their risk of progression would identify who actually needs this diet of regular testing/monitoring and those who, frankly, could be left alone for a bit longer. To me, the key conundrum with glaucoma is ensuring that patients take this disease seriously, even though it might be completely unnoticeable to them. On the clinician side of the equation, we need a better understanding of what the measurements we’re taking in glaucoma patients mean – how does it affect simple, everyday things like reading, finding something on a supermarket shelf, driving safely, or recognizing someone’s face? As our understanding of glaucoma evolves, I believe it’s important that we ensure we’re listening to people who are in many ways the real glaucoma experts – the patients.David Crabb is Professor of Statistics and Vision Research and Director of the Centre for Applied Vision Research at City University London. He leads a multi-disciplinary research group (@crabblab) made up of vision scientists, optometrists, psychologists, mathematicians and computer scientists.

References

- DP Crabb et al., “How does glaucoma look? Patient perception of visual field loss”, Ophthalmology, 120, 1120–1126 (2013). PMID: 23415421. FC Glen et al., “Impact of superior and inferior visual field loss on hazard detection in a computer-based driving test”, Br J Ophthalmol, 99, 613–617 (2015). PMID: 25425712. AA Black et al., “Inferior visual field reductions are associated with poorer functional status among older adults with glaucoma”, Ophthalmic Physiol Opt, 31, 283–291 (2015). PMID: 21410740. KA Turano et al., “Association of visual field loss and mobility performance in older adults: Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study”, Optom Vis Sci, 81, 298–307 (2004). PMID: 15181354. FC Glen et al., “A qualitative investigation into patients’ views on visual field testing for glaucoma monitoring”, BMJ Open, 4, e003996 (2014). PMID: 24413347.