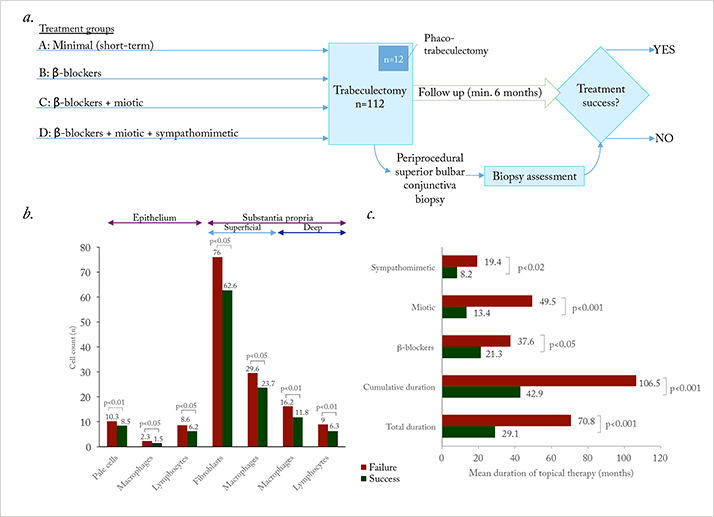

November 1994 saw the publication of two landmark papers in the field of glaucoma medicine (1,2). Broadway et al. had performed a prospective study that followed 124 patients with glaucoma who underwent trabeculectomy (or phaco-trabeculectomy and intraocular lens placement; Figure 1a). They knew the type, number and duration of topical ocular antihypertensive drug(s) used before patients underwent filtration surgery (during which conjunctival biopsies were taken) and patients were followed-up for a minimum of six months afterwards. What they found was that, irrespective of the drug, pre-surgical topical glaucoma therapy use over a period of three or more years induced a significant increase in subclinical inflammation in the conjunctiva (Figure 1b). Further, the longer the topical glaucoma therapy use (of any type) before surgery, the greater the chance of filtration surgery failure (Figure 1c).

The study raised a key question: what was the cause? Was it the active drug or something else in the formulation? One thing common to all commercially available topical glaucoma formulations at the time was that they contained preservatives – usually the quaternary ammonium surfactant, benzalkonium chloride (BAK) (3). At the concentrations used in eyedrops, BAK acts as a bactericide, dissolving bacterial cell membranes. Unfortunately, it also has cytotoxic effects on the cornea and conjunctiva, and can induce a number of deleterious effects to the ocular surface (see Figure 2).

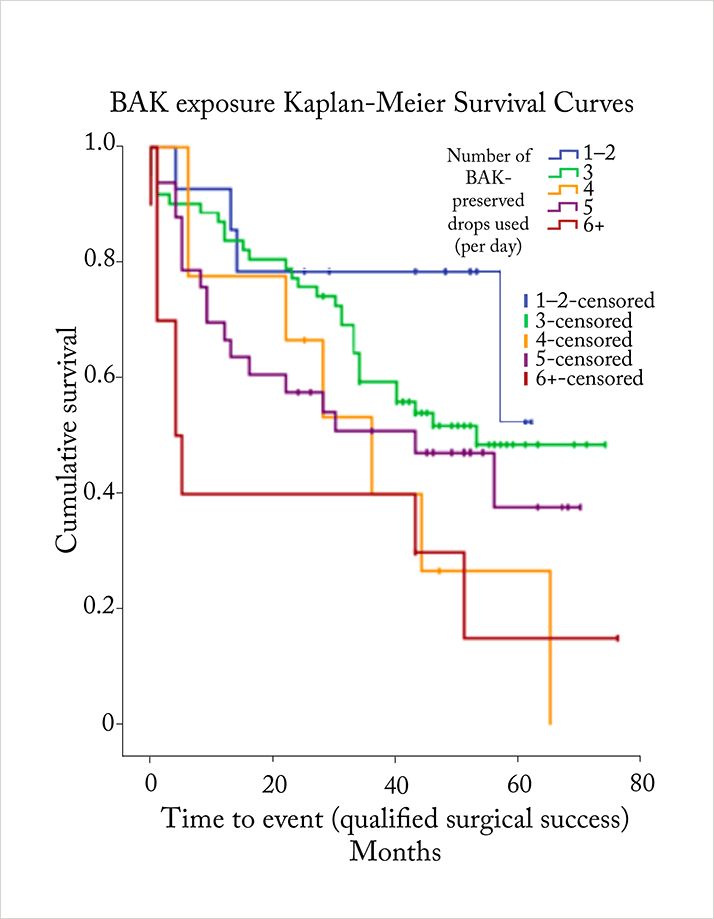

In 2013, Boimer and Birt performed a retrospective chart review of 128 patients with glaucoma who underwent trabeculectomy (4). Like Broadway et al, they knew each patient’s preoperative topical glaucoma therapy regimen, and as before, patients were followed up for an extended period — in this case, a minimum of two years. But this time, their principal focus was to determine the relationship between preoperative BAK exposure (as determined by the number of BAK-containing topical therapies used) and the postoperative time to trabeculectomy failure. In this study, the median number of BAK-containing topical glaucoma therapies that patients used was three (range 1–8), and just under half of all patients (47.7 percent) achieved complete surgical success. The relationship to the preservative and treatment failure was clear, though. Treatment failure came significantly sooner in patients receiving higher preoperative daily doses of BAK, relative to those receiving a lower daily dose (p=0.008). Even after accounting for other risk factors for treatment failure with proportional hazard modeling, the main effect of BAK exposure – treatment failure – was still significant (HR 1.21, p=0.032).

The question then becomes: how do preservatives increase the risk of trabeculectomy failure? It appears that, postoperatively, the ocular surface inflammation that was induced by pre-surgical topical therapy continues to play an important role. The conjunctiva interacts with aqueous humor, and subconjunctival fibrosis can lead to aqueous outflow blockage, resulting in trabeculectomy failure (3).

If preoperative inflammation underlies postoperative fibrosis – and therefore surgical outcome – then this is certainly something to be borne in mind when assessing the most appropriate ocular hypertension management regimen for patients under your care. It’s particularly important because surgery is often necessary to control IOP in a great number of patients who have previously received chronic, topical glaucoma therapy (3). Put simply, preservatives can be a problem.

Thankfully, there are non-preserved topical ocular antihypertensive agents available that are just as effective as preserved formulations (5,6), and are certainly worth considering when determining the most appropriate treatment regimen for your patients.

Job code: STN 0917 PO 00032 (EU).

Date of preparation: September 2015.

The study raised a key question: what was the cause? Was it the active drug or something else in the formulation? One thing common to all commercially available topical glaucoma formulations at the time was that they contained preservatives – usually the quaternary ammonium surfactant, benzalkonium chloride (BAK) (3). At the concentrations used in eyedrops, BAK acts as a bactericide, dissolving bacterial cell membranes. Unfortunately, it also has cytotoxic effects on the cornea and conjunctiva, and can induce a number of deleterious effects to the ocular surface (see Figure 2).

In 2013, Boimer and Birt performed a retrospective chart review of 128 patients with glaucoma who underwent trabeculectomy (4). Like Broadway et al, they knew each patient’s preoperative topical glaucoma therapy regimen, and as before, patients were followed up for an extended period — in this case, a minimum of two years. But this time, their principal focus was to determine the relationship between preoperative BAK exposure (as determined by the number of BAK-containing topical therapies used) and the postoperative time to trabeculectomy failure. In this study, the median number of BAK-containing topical glaucoma therapies that patients used was three (range 1–8), and just under half of all patients (47.7 percent) achieved complete surgical success. The relationship to the preservative and treatment failure was clear, though. Treatment failure came significantly sooner in patients receiving higher preoperative daily doses of BAK, relative to those receiving a lower daily dose (p=0.008). Even after accounting for other risk factors for treatment failure with proportional hazard modeling, the main effect of BAK exposure – treatment failure – was still significant (HR 1.21, p=0.032).

The question then becomes: how do preservatives increase the risk of trabeculectomy failure? It appears that, postoperatively, the ocular surface inflammation that was induced by pre-surgical topical therapy continues to play an important role. The conjunctiva interacts with aqueous humor, and subconjunctival fibrosis can lead to aqueous outflow blockage, resulting in trabeculectomy failure (3).

If preoperative inflammation underlies postoperative fibrosis – and therefore surgical outcome – then this is certainly something to be borne in mind when assessing the most appropriate ocular hypertension management regimen for patients under your care. It’s particularly important because surgery is often necessary to control IOP in a great number of patients who have previously received chronic, topical glaucoma therapy (3). Put simply, preservatives can be a problem.

Thankfully, there are non-preserved topical ocular antihypertensive agents available that are just as effective as preserved formulations (5,6), and are certainly worth considering when determining the most appropriate treatment regimen for your patients.

Job code: STN 0917 PO 00032 (EU).

Date of preparation: September 2015.

References

- DC Broadway, et al., Arch Ophthalmol, 112, 1446–1454 (1994). PMID: 7980134. DC Broadway, et al., Arch Ophthalmol, 112, 1437–1445 (1994). PMID: 7980133. C Baudouin, Dev Ophthalmol, 50, 64–78 (2012). PMID: 22517174. C Boimer, CM Birt, J Glaucoma, 22, 730–735 (2013). PMID: 23524856. T Hamacher, et al., Acta Ophthalmol Suppl, 242, 14–19 (2008). PMID: 18752510. A Shedden, et al., Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 248, 1757–1764 (2010). PMID: 20437244.