Originally, I wanted to do a chemistry PhD – I only switched to medicine during my third year. At first, I was aiming for a residency in radiation oncology, but then realized I wasn’t psychologically equipped for a specialty where the doctor can’t win! And that’s why I went into ophthalmology – you can actually cure people.

I started out as a glaucoma surgeon but adopted phaco very early (before it became popular), so I never really considered the two as separate disciplines. I still think the glaucoma surgeon should be a great cataract surgeon as well. All the cases that require real skill to treat – such as pseudoexfoliation, traumatic glaucoma, pediatric patients and small pupils – are found in glaucoma patients.

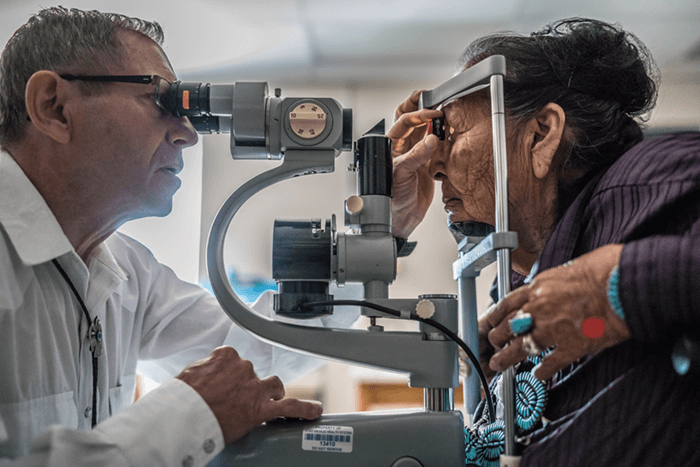

Knowing that I was one of a small number of surgeons willing to teach others is very satisfying. I’m also pleased that I supported an environment that enabled formation of the ASCRS. Back when Charles Kelman was being treated as a pariah and the Academy did not accept phacoemulsification, we had to develop a space for people to discuss phaco, because there was nowhere else to go. The meetings were run by David Kartcher at the Beverly Hills Hilton and, from that, he eventually got asked to set up a new organization, whichis the ASCRS. Finally, my international ASC work has been immensely rewarding: as Senior Medical Director of Moran’s Global Outreach Division, I’ve worked in developing countries including South Sudan, Tanzania, Guatemala, Nepal, Haiti and Micronesia.

Don’t be in too much of a hurry; maintain soft fingers in every single maneuver; and remember that no part of the phaco procedure is inconsequential. Even the primary incision step is critical; too flat, and your second instrument will cause corneal stria, too steep and fluid will pour out of the eye; if the wound is incorrectly done you may get kimosis, and if it’s too tight you may get a corneal burn…

Also, if you get a problem, stop and analyze the situation. Above all, don’t immediately come out of the eye; first, stop the ingress of fluid; next, inject viscoelastic, and then look and think. Break down each part of the surgery to identify the cause of the problem.

Finally, be aware that the only way to have no complications is to do no surgery! Regardless of how good you are, one day something will go wrong. Your complication rate may go down over time, but it will never reach zero. You’ll get better with time, but to speed up the development of your skills, I recommend that you video and revisit every case you do – it’s amazing what you find out about your own technique!

I have always been passionate about helping others. And when you fix somebody’s eyes in the developing world, you free up two people: the blind person and their caregiver. It makes a massive difference in those countries, and I think it will benefit the developed world too, eventually. It’s like the concept of a butterfly’s wings starting a wind that goes far; I believe that kindness to individuals ultimately helps society as a whole.

Of course, working in those environments isn’t always easy. Sometimes, we’d have to carry instruments to avoid them being impounded and incurring fees at customs; I’ve had to wear the same clothes for two weeks because all my hand luggage space was taken up by a donated phaco unit! And in South Sudan, we had to negotiate with three rival tribes who all spoke different languages, so we needed three interpreters. We eventually got permission from them to treat patients, but, after two years, North Sudan closed the borders, and we had to cease operations and get out. I’ve also spent time in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran – it’s interesting how, despite sanctions, they had all the best American equipment! One of the beautiful aspects of ophthalmology is that we can share cures for blindness, and I hope that contributes to the spread of peace.

I think we can learn a lot, partly because our future needs will be met by a combination of high-tech and low-tech. Look at miLOOP: it’s a modern, much nicer version of an old technique – the wire snare. Similarly, India and China are now developing low-cost phaco units, and I think we may also see those machines being adopted in the developed world. We can also learn from their attitude to waste and recycling. Over there, there’s no such thing as a single-use instrument, but their complication rate is no higher than ours; do we really need to focus on disposables so much? Finally, we can pick up very useful skills by working in developing countries; for example, you see much harder cataracts there than in the West. And we shouldn’t forget that people in need exist in the developed world too: that’s why, for example, we run a free clinic for the homeless in Salt Lake City. The skills and low cost innovations we see in the developing world could well benefit those from any resource-poor context.