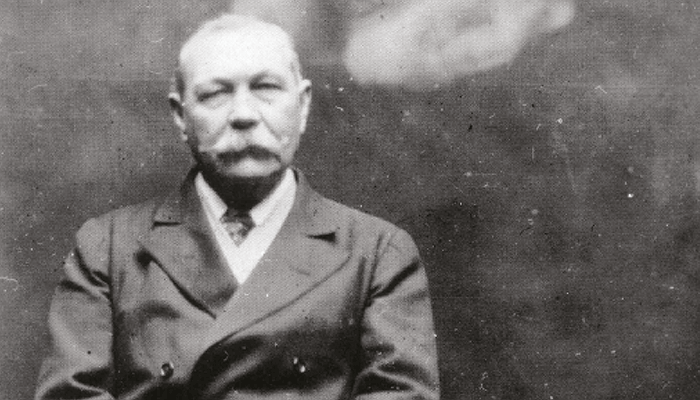

Almost everyone has heard of Sherlock Holmes. It is even fairly common knowledge that the creator of the world’s most popular fictional detective was a physician. What is less well-known is the fact that he specialized in ophthalmology.

Arthur Conan Doyle graduated in 1881 with a Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery degree from the University of Edinburgh. Following his graduation, Doyle moved to Portsmouth, where he received training in refraction and retinoscopy at the city’s Eye and Ear Hospital. After a brief period of further training in Vienna and Paris, Doyle decided to establish his own ophthalmology practice in London, sealing his title as an official member of the Ophthalmological Society of the United Kingdom. But his career progression occurred just as he was beginning to see increasing prosperity and recognition as a writer. Soon, he realized that he could achieve far more if he devoted himself completely to literature… and the rest is history!

The Adventure of the Banned Spectacles

So how did Doyle’s ophthalmology background make its way into his books? There are only two Sherlock Holmes stories in which Doyle used his ophthalmic experience. In “The Adventure of Silver Blaze,” a cataract knife is found at the crime scene and in “The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez,” spectacles become the evidence used to identify a suspect. Interestingly, in what some might call life mimicking art, Doyle himself would defend a highly myopic suspect in his letters to both The Lancet and The BMJ, arguing that, without spectacles, the defendant would have been unable to conduct all of the demanding activities related to his alleged crimes.

The Man Behind the Man in the Deerstalker Hat

In his non-Sherlockian novel, “The Stark Munro Letters,” Doyle humorously presents the benefits of practicing ophthalmology. He states:

“What’s the use of a village practice with a miserable 3,000 or so a year for a man that wants room to spread? […] I’ve taken to the eye, my boy. There’s a fortune in the eye. A man grudges a half-crown to cure his chest or his throat, but he’d spend his last dollar over his eye. There’s money in ears, but the eye is a gold mine!

“South America […] not a man in it who could correct an astigmatism. What do they know of modern eye-surgery and refraction? Why, dammy, they don’t know much about it in the provinces of England yet, let alone Brazil […] I’m there to squeeze the continent. I work a town at a time. I send on an agent to the next town to say that I am coming […] no need to go back to Europe. Here’s Europe come to you. Squints, cataracts, iritis, refractions […]”

“You will need to speak Spanish,” said I.

“Tut, it does not take any Spanish to stick a knife into a man’s eye. All I want to know is, ‘Money down – no credit.’ That’s Spanish enough for me.”

Another quote from Doyle presents him as a great advocate of humanism in medicine. He wrote:

There is another facet which life will teach you, which is the value of kindliness and humanity as well as knowledge […] A strong and kindly personality is as valuable an asset as actual learning in a medical man. I do not mean that trained urbanity which has been called “the bedside manner,” but the real natural benevolence which may be slowly cultivated in the character, but cannot be stimulated by any forced geniality. I have known men in the profession who were stuffed with accurate knowledge, and yet were so cold in their bearing, so unsympathetic in their attitude, assuming the role rather of a judge than a friend, that they left their half-frozen patients all the worse for their contact.

His Last Bow

Conan Doyle was knighted on October 24, 1902 by King Edward VII. Contrary to what one might expect, this was not due to his fictional pursuits, but as a result of his contributions to a nonfictional pamphlet regarding the Boer War. Doyle died in 1930 after creating a body of work containing nearly 200 novels, short stories, poems, historical books, and pamphlets. He lies in Minstead churchyard in the New Forest in Hampshire; the epitaph on his gravestone reads, “Steel true, blade straight.”

References

- AC Doyle, “The romance of medicine,” St Mary’s Hospital Gazette, 16, 100 (1910).

- AE Rodin, JD Key, “Humanism and values in the medical short stories of Arthur Conan Doyle,” South Med J, 85, 528 (1992). PMID: 1585207.

- Arthur Conan Doyle (2022). Available at: https://bit.ly/3RfFCZt.

- Internet Archive (2022). Available at: https://bit.ly/3r9uIcW.

- JG Ravin, C Migdal, “Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: the author was an ophthalmologist,” Surv Ophthalmol, 40, 237 (1995). PMID: 8599161.

- M Sen, SG Honavar, “Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: The adventures of a literary ophthalmologist,” Indian J Ophthalmol, 69, 3394 (2021). PMID: 34826966.

- Project Gutenberg (2022). Available at: https://bit.ly/3BNpEA4.