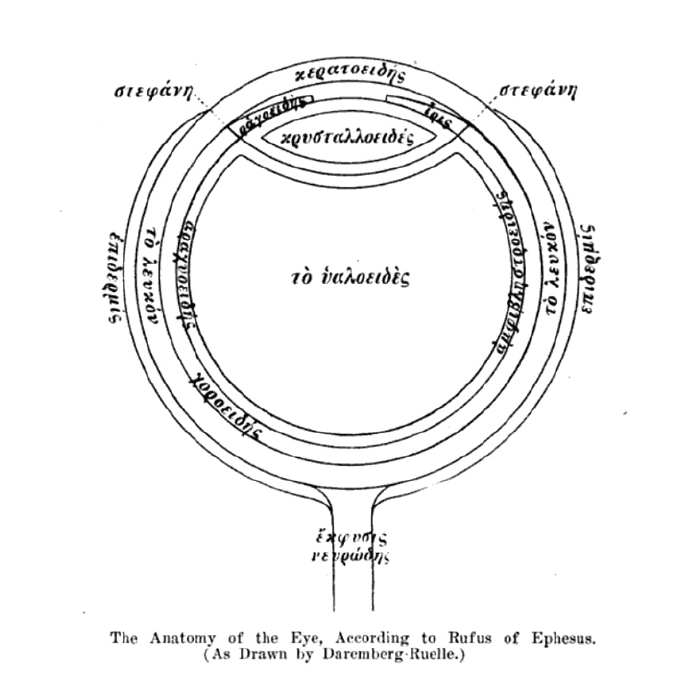

Figure 1. The anatomy of the eye, as described by the ancient Greek author Rufus of Ephesus, with an anteriorly located crystalline lens (3)

Ancient Greek authors such as Rufus of Ephesus and Galen of Pergamon described the crystalline lens. They had seen it themselves – they had dissected the eyes of animals, such as macaques – and thus correctly understood that the lens is anteriorly located (Figure 1). Galen noted that the lens equator is close to the iris root and to the peripheral cornea (1,2).

In the ninth century, we come to our first myth. Hunayn ibn Ishaq of Baghdad promulgated the idea that the crystalline lens was in the exact center of the eye (Figure 2). He did not justify this statement on the grounds that he had performed dissections; rather, he believed the crystalline lens was the most important part of the eye, and therefore, a central location seemed most sensible (1,4).

The medieval authors followed the ancients in believing that the crystalline lens was the “seat” of vision, and that the opacity displaced by cataract couching lay anterior to the lens. Hunayn’s myth of the central crystalline lens lasted for seven centuries. Finally, in the 16th century, dissections convinced anatomists, such as Realdo Colombo, of the anterior location of the lens (1,5).

In the 20th century, we come to our second myth. In 1901, ophthalmologist and historian Hugo Magnus noted that the ancient Roman author Celsus described a couching needle entering an empty space. Magnus assumed that Celsus must have thought the lens was located more posteriorly than it really was. What Magnus failed to consider in this analysis was that it was standard practice even among the Greek authors to describe an empty space in front of the lens. The purpose was to indicate that there would be decreased resistance when scleral penetration was complete (as Celsus noted), and that one could see the couching needle anterior to the lens (as Paulus Aegineta noted). Galen also described how the couching needle could move in the space anterior to the lens, even though he clearly understood the lens to be anteriorly located (1, 2).

Magnus went on to hypothesize that the medieval authors, such as Hunayn, might have inherited the idea of the central crystalline lens from Celsus. In Magnus’ defense, this is a reasonable enough hypothesis to explore. But it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Celsus’ primary purpose was to describe cataract surgery, rather than anatomy. His anatomic descriptions might have some ambiguities, but his descriptions are entirely compatible and consistent with the anatomic descriptions of his Greek sources. Moreover, there is no evidence that medieval authors such as Hunayn had read Celsus (1,3).

Unfortunately, Magnus drew a picture of one hypothesis (that Celsus believed that there was a tiny crystalline lens in the center of the eye), but did not draw a picture of the alternative hypothesis (that Celsus was simply passing on knowledge gleaned from Greek anatomists who had seen the lens to be located anteriorly). Because a picture is worth a thousand words, the myth that the ancients believed that the crystalline lens is located in the center of the eye has been dutifully passed down over the past century, often by people who have never read the works of Celsus, Rufus, Galen, or Magnus. We debunked this myth in 2016. Nonetheless, the figure drawn by Magnus and the claim that the ancients believed the lens to be in the center of the eye, are still contained in the Basic and Clinical Science Course used by ophthalmology residents (6). In reality, the ancients knew where the lens was located, because they were the ones who discovered it.

Figure 2. The anatomy of the eye with a central crystalline lens, as described by Hunayn of 9th century Baghdad

References

- CT Leffler et al., “A medieval fallacy: the crystalline lens in the center of the eye,” Clinical Ophthalmology, Apr 8, 649 (2016).

- CT Leffler et al., “Glaucoma in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds,” in CT Leffler (ed.), The History of Glaucoma, 1, Wayenborgh: 2020.

- TH Shastid, “Ophthalmology, History of,” in CA Wood (ed.), The American Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Ophthalmology, 8588, Cleveland Press, 1917.

- CT Leffler et al., “Glaucoma in the medieval Arabic world,” in CT Leffler (ed.), “The History of Glaucoma,” 47, Wayenborgh: 2020.

- CT Leffler, E Peterson, “Glaucoma in the European Middle Ages and Renaissance,” in CT Leffler (ed.), “The History of Glaucoma,” 75, Wayenborgh: 2020.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2020–2021 BCSC Basic and Clinical Science Course. 11. Lens and Cataract. Available from: https://www.aao.org/education/bcscsnippetdetail.aspx?id=529008b6-b022-4ed8-a55a-44dcd0d31e4b Accessed July 14, 2024.