Credit: Robert James (1703-1776)., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Since antiquity, observers have understood that a favorable outcome from cataract surgery was less likely for congenital cases. But in the 18th century, a favorable outcome was used by the surgeon to compare his works with the miracles of scripture. English ophthalmologist Roger Grant advertised in 1709 that he had cured a 20-year-old man who had been born blind. However, it was later revealed that, although the young patient had suffered from a corneal “speck” (most likely a small opacity), he had not been completely blind and his vision had improved little with the procedure. It was also discovered that the certificate from a local cleric attesting to the healing had been forged (1,2).

Congenital cataract surgery also came into vogue as a model for understanding innate versus acquired relations between sensory modalities, such as vision and touch (2). Cleric and philosopher, George Berkeley, heard about Grant’s case in 1709, and indicated that he would be interested in probing sensory responses in similar cases of healing from congenital blindness (3). When Berkeley returned to London in 1724, he met Sir Daniel Dolins, who was also trained as a philosopher, and, like Berkeley, was in the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge. Berkeley appointed Dolins to a committee to receive funds for a college Berkeley hoped to establish in Bermuda.

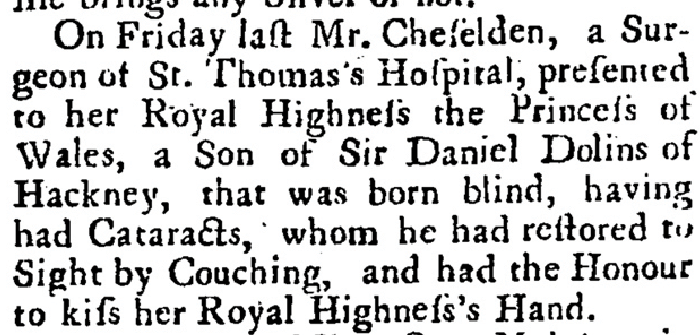

As it happens, Dolins had a blind son, also named Daniel, who had cataract couching performed in 1727 at age 13 by surgeon William Cheselden. (The newspaper report which allowed us to determine that Daniel was Cheselden’s patient was first identified in 2021 [Figure 1]). Cheselden and the patient were invited to Princess Caroline’s court, and Cheselden was permitted to kiss her hand. It is known that Berkeley debated religion and philosophy weekly at Caroline’s court. Cheselden was subsequently named the surgeon to Queen Caroline. This case report is one of the most famous in all of medicine, and Berkeley claimed the report supported his own philosophical theories.

However, it seems that Berkeley might have had a hand in drafting the report. It was signed with an incorrect spelling (“Chesselden”) and written in the second person (“we”), employing language more typical of Berkeley than of Cheselden.

The report describes the younger Daniel’s positive emotions, and the visual tasks that he hoped to accomplish, in an attempt to falsely convey the impression the young patient could see better after the procedure. In fact, it is not specified that Daniel accomplished any visual tasks after the surgery at any time. Additionally, his tutor indicated that Daniel was blind from the age of two, rather than congenitally, as had been previously supposed. We also know from surgeon Peter Kennedy and from Daniel’s tutor that the patient suffered postoperative complications, and that his vision never actually improved. Daniel died of a chronic illness at the age of 30 in 1743, but he said, “My sufferings are nothing and I am happy” (2).

Unfortunately, these cases teach us very little about amblyopia or cross-modal sensory linkage. They do demonstrate striking mendacity, conflicts of interest, and unprofessionalism. And they remind us, even today, that we should focus on the patient, rather than our own careers.

Newspaper report from March 14, 1727 from the Daily Journal (London), noting that William Cheselden had performed cataract couching on the son of Sir Daniel Dolins, who was said to be born blind.

References

- CT Leffler et al., “Congenital cataract surgery during the early enlightenment period and the Stepkins oculists,” JAMA ophthalmology, 132, 883 (2014).

- CT Leffler et al., “The first cataract surgeons in the British Isles,” American Journal of Ophthalmology, 230, 75 (2021).

- G Berkeley, An Essay Towards a New Theory of Vision, 2nd edition, 197. Rhames: 1709.