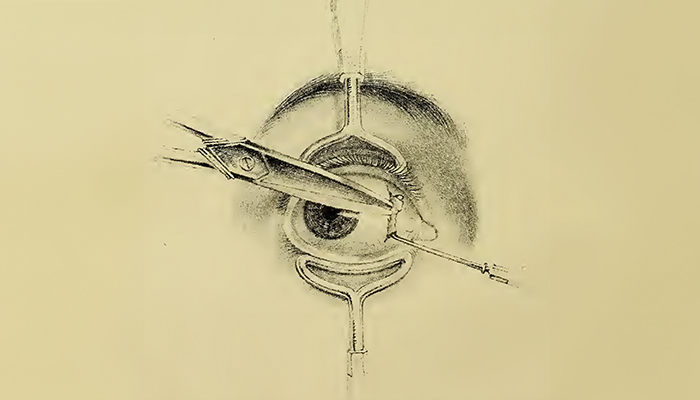

Figure 1. Strabismus surgery in 1840 (2).

Conventional accounts stipulate that the era of strabismus surgery began in 1838, when Louis Stromeyer (1804–1876) of Hannover, Germany, published his experiment with the procedure on a cadaver (see Figure 1). So, we were quite surprised to discover in newspaper databases that the idea of strabismus surgery actually “went viral” in America the year before – in 1837. New York oculist John Scudder (1807-1843) claimed to have performed strabismus surgery on a girl in Ballston Spa in upstate New York on August 1837 (1). His description of the procedure was published in dozens of American newspapers and medical journals. However, Scudder did not provide evidence to support his claim, which came to be regarded as a hoax. But, even if it was a hoax, did Scudder’s claim lead to Stromeyer’s publication of the idea?

And who was John Scudder? He was already known by his father’s friends to be “remarkably smart” when he was 14 years old. At 16, he was tasked with managing the American Museum, which his family owned. At that time, Scudder published a museum guide – a book-length encyclopedia describing the exhibits. The guide noted that the museum held an enormous magnet (3).

Scudder completed several years of medical school at Columbia, but did not finish the program. He began practice as an “oculist” by 1827. He made detailed artificial eyes, and may have been the first in the United States to do so (3, 4). Through the use of optical illusions, the pupils of his prosthetic eyes would appear to constrict in bright light.

Scudder sought to have the prostheses move along with the real eye. It may have been just a short time before he became interested in optimizing the movement of real eyes (i.e., curing strabismus). He claimed to have some type of treatment for “squinting” in 1832. In 1833, he showed to a newspaper editor a boy who had developed strabismus following trauma, and was cured after Scudder “operated” on him. As Scudder did not describe his method, it is possible that he merely placed an artificial eye.

In 1837, when presented with a young girl with a metallic foreign body lodged in her eye, other oculists were unable to remove it. Scudder gave the girl an “anodyne” (a general term for a pain-reliever) to help her sleep, and then used a powerful magnet, presumably the magnet from the museum, to remove the foreign body. Although this case preceded the era of general anesthesia, conceivably Scudder could have given her a preparation with agents such as alcohol, opium, or belladonna.

In August 1837, Scudder claimed to have cured a “young lady” in Ballston Spa of strabismus by cutting some of the fibers of an extraocular muscle: “The operation was performed by cutting some of the fibers of the muscle which held the eye obliquely; the consequence was, that the opposite muscle immediately brought the eye in its proper line of vision, and the unpleasant deformity of squinting was instantaneously removed” (3).

Hoax or not, could Stromeyer of Germany – who is credited with initiating the era of strabismus surgery by dividing the medial rectus muscle of a cadaver in 1838 – have heard of Scudder’s idea? An American reviewer in 1842 suggested as much. The most likely link would be Stromeyer’s student, William Detmold (1808–1894), who had studied with Stromeyer in Hannover in 1836 (5). Stromeyer had performed tenotomy for clubfoot by 1831 (6), and was interested in other applications of tenotomy. In April 1837, he noted that pain throughout the body was often associated with muscle spasm, and therefore proposed that inferior or superior oblique tenotomy might help with eye pain, in conditions such as glaucoma (7).

Detmold moved to New York City, arriving in May 1837. Therefore, he was in New York in August 1837, when Scudder claimed to have cured a young lady of strabismus. The medical community might have been aware of Scudder’s claim because it was reported that “the whole faculty ridiculed” it.

Detmold performed his first surgery for clubfoot in New York on September 8, 1837 in the presence of Edward Delafield, founder of the New York Eye Infirmary (8). Thus, Detmold was connected with the ophthalmic community. In January 1840, he made the first mention of strabismus surgery in America after Scudder’s report: “Squinting, which arises from a spasmodic action of the muscles of the eye, could no doubt be cured by a division of those muscles…Stromeyer makes a similar suggestion (9).” In April 1840, the successful strabismus surgeries of Dieffenbach of Germany were reported in New York (10). On September 14, 1840, Detmold became one of the first to perform strabismus surgery in the United States (11). As a surgeon interested in tenotomy, specifically for strabismus, it is reasonable to believe that Detmold would have mentioned in any correspondence with his mentor and friend Stromeyer the concept, widely circulated in New York in 1837, of myotomy for strabismus. Thus, Scudder’s publication of myotomy for strabismus might have initiated the modern era of strabismus surgery.

So, what became of John Scudder? He lived long enough to see the frenzy when strabismus surgery reached American shores in 1840. The idea for which he had been ridiculed became the next big thing in ophthalmology. However, Scudder’s health was failing, and the family museum had to be sold to P.T. Barnum in 1841. In 1843, Scudder died in abject poverty at the age of 36 years in the Albany almshouse. His obituaries recalled that he was “possessed of a mind of great powers, original in its conceptions, quick as lightning in its perceptions, and able by its single and unassisted efforts to grasp any science and grapple, giant-like, with any theory, the dawn of his earthly career broke in unclouded brilliance.” The obituary also noted that, if it were not for his addiction to rum, he “would have been an honorable and useful member of society,” (12).

References

- L. Stromeyer, Beiträge zur Operativen Orthopädik, oder Erfahrungen über die subcutane Durchschneidung verkürzter Musklen und Sehnen, Helwingschen Hof-Buchhandlung: 1838.

- EW Duffin, Practical remarks on the new operation for the cure of strabismus or squinting, 93, Churchill: 1840.

- CT Leffler et al., “American Insight Into Strabismus Surgery Before 1838,” Ophthalmol Eye Dis. (2017). PMID: 28932129.

- CT Leffler et al., “Ophthalmology in North America: early stories (1491-1801),” Ophthalmology and Eye Diseases (2017). PMID: 28804247.

- AR Shands, “William Ludwig Detmold: America's first orthopedic surgeon,” Mil Med., 133, 563 (1968).

- PF Smith, “Louis Stromeyer (1804-76): German orthopedic and military surgeon and his links with Britain,” J Med Biogr, 14, 65 (2006).

- L. Stromeyer, “Physiologische Bemerkungen am Krankenbette,” in Johann Ludwig Casper (ed.), Wochenschrift für die Gesammte Heilkunde, Reimer: 1837. https://archive.org/details/wochenschriftfr00caspgoog

- W. Detmold, “Report of several Cases of successful operation for Club-foot by the division of the Tendo Achillis,” American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 43:105 (1838). Available at https://archive.org/stream/americanjournal221838thor#page/104/mode/2up

- W. Detmold, “An Essay on Club-foot, and Some Analogous Diseases,” New-York Journal of Medicine and Surgery (January 1840).

- No author listed. Cure of Strabismus. Professor Drieffenbach [sic] of Berlin, has actually cured three individuals of squinting by this operation, New-York Journal of Medicine and Surgery (April 1840). Available at: https://archive.org/stream/newyorkjournalof2184unse/newyorkjournalof2184unse_djvu.txt

- AB Judson, “Subcutaneous Tenotomy. Biographical Notes,” Transactions of the American Orthopedic Association (1899). Available at: https://archive.org/stream/b22335250#page/4/mode/2up

- No author listed, “Death of Doctor John Scudder, the Oculist,” Daily Evening Transcript, Boston (Feb. 7, 1843).