The only time I dared to rebel against my father was when he wanted me to go and join the ear, nose and throat department and I said, “No, indeed, I want to be independent!” But afterwards, I realized that it wouldn’t have mattered in the long run at all. It just so happened that I winged it at the time, and I had some friends in the ophthalmology department, and that was it.

Yes, I liked the professor there very much. His name was Larsson, and he was a very popular figure and very protective and so on, and gave me a great deal of freedom. I also had a PhD in biochemistry, studying metabolism of the proteoglycans in the cornea, so I was also a little bit of an amateur biochemist.

I was influenced by my friend, David Morris. He was a brilliant physiologist, and I was drawn in by his vision of fluid physiology. So I did some work along those lines. Although I didn’t see him very often, and so I had never really worked with him, I was very inspired by him. I did some physiology – corneal edema physiology, and so on, and I gradually shifted my interest from biochemistry to fluid physiology.

And then, of course, I am a clinician, and I was recruited to Harvard in 1958. And they told me that I could travel for half a year and then I should remain in Boston for a minimum of three years. That was such an eye-opener to me, and from a research point of view, it was a wonderful time. The US National Institutes of Health was building up rapidly, and had huge funds, but the people who were interested or trained in eye research were very few. So you could essentially send in a poorly written requisition for money, and you got it the next day. And that was wonderful. Since I told people I was interested in the cornea; they thought that I had corresponding clinical knowledge and insight. This wasn’t entirely true at the time, but they sent me tons of patients, and I learned on the job. Then, I started a cornea service – actually the world’s first organized cornea service with clinical and surgical training – and that worked really well.

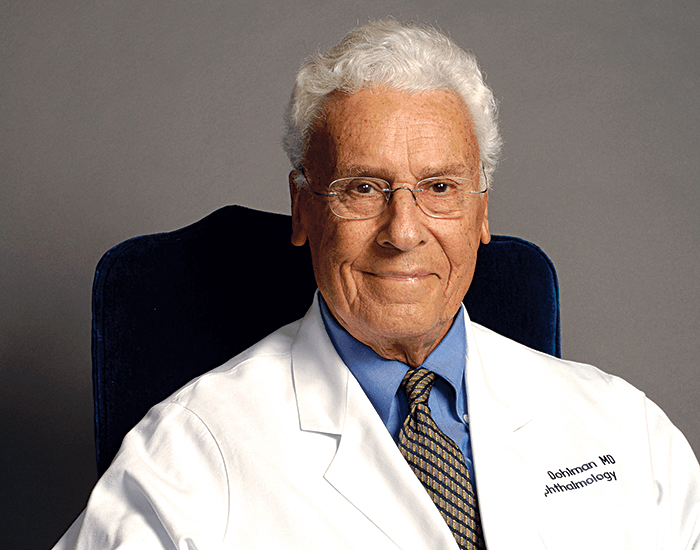

Absolutely. I had 15 very dry years when it came to research. I could cheer on my younger colleagues, but I didn’t have any real involvement. We had a staff of about 300, and it was very demanding. I managed to build a reasonable department, and things went quite well – although more slowly than I had hoped – but research was out of the question. When I retired as chair of ophthalmology in 1989, I moved on to translational research and teaching. I’m now 93, and I’ve been able to revisit my old interests – right now I’m interested in artificial corneas.

Well, there were no grandiose thoughts. I had done some work on keratoprostheses earlier, but I had mostly stopped because of my administration work. I saw some cases that were really spectacular, but it was still very dangerous. I thought it could be improved.

After having barked up an entire forest of wrong trees, I settled for one design. It wasn’t very original, similar things had been described before. But I started there, and I developed an interest particularly in the biology surrounding the keratoprosthesis, which is really the key. And since that time, with my coworkers (a very large number of them, it must be said), it has improved slowly but steadily, and the complications are becoming less and less of an issue.

Then somewhat to my dismay, I found that once the corneal complications were taken care of to a reasonable degree, there were other problems in the back of the eye. The eyes that can benefit from keratoprosthesis, essentially end-stage eyes, are very damaged. They usually have glaucoma, and that glaucoma was getting worse, and we were seeing retinal detachment and other issues. These were more fundamental and more difficult problems to solve. We’ve made some headway, but there’s still a long way to go.

But despite this, it has taken off – we didn’t really market it, but it caught the interest of the world’s corneal surgeons. We started to get orders and sell them, but we didn’t keep any money for ourselves, it went to the institute, research, manufacture and distribution. I believe around 12,000 or so have been implanted so far, and that number is increasing. And although it isn’t perfect, it has made a difference to a lot of patients.

No, I’m concentrating on the artificial cornea. One line I’m looking at is the role of infliximab, for instance, in suppressing inflammation. And working with miniature keratoprosthesis in mice, looking at inflammatory cytokines and the possibilities there. Another line is improving the keratoprosthesis; making it better, simpler, and cheaper. In all these matters I’m collaborating with colleagues, and reaching out to people I know in fields where I lack expertise, and we also have a number of fellows too. The work that I have done personally has been minimal, but the fellows do a lot, and then they go out into the world and continue elsewhere, which is fantastic.

My style is nonexistent! It’s a laid-back collaboration. I have been fortunate in having not only a large number of fellows over the years, but also many who have been very bright, and very capable. They’ve taught me as much as I taught them.

Well, I am not a dispenser of wisdom in this respect. But I think it is important for younger people to focus their work – not doing a little here, a little there, but building on what they’ve done before. Stick to one topic. Have a clinical goal and work towards that – year after year, or even decade after decade, and you will see progress. So a little patience, friendship, and collaboration. Respect young people and their aspirations. And help them with those aspirations – trying to get them placed is important.

Yes, I would say so. I’ve never given much thought to these things, but I think what one should avoid is micromanagement, which irritates people. You should delegate a lot of responsibilities and then concentrate on recruiting the best and the brightest. That, I think, goes for any department in any discipline.

Perhaps all my bright junior colleagues who I have helped to inspire. And not only me, but all of our large corneal staff. And we’re proud of what they have, in turn, achieved and accomplished. And I’m happy to think of all the people we have been able to help with the keratoprosthesis. We now hope to use it to help, if possible, the developing world. These corneal diseases exist there too, but resources are much poorer.

Then, of course, you want a long and healthy life. And for that, I can thank two things: genes and luck. Nothing else. I can’t take credit for it – for anything, actually. You need the years to be able to devote to work, and when it comes to any form of research, basic or clinical or translational, you need to stay with it and put in the time. There are many things I have done wrong in my life, but that is the one thing that I happened to do right. I cannot take the credit for my longevity – I’m now 93 and I’m still working full-time – but I can say it has always been interesting. It has been a very rich life.