As the prevalence of diabetes increases worldwide, so too do the complications relating to it, such as diabetic macular edema (DME). We currently have a range of treatment options, varying from surgical interventions (for example, focal or diffuse laser treatment) to intravitreally administered therapeutics (for example, anti-VEGF and steroids).

Case presentation We report our experience with a sixty-year-old, Caucasian, type II diabetic female, with left amblyopia, systemic hypertension and hypercholesterolemia who presented with unaided visual acuities at 6/6 OD and 6/9 OS in January 2006. Her regular medications included metformin, ramipril, atorvastatin, and bisoprolol.

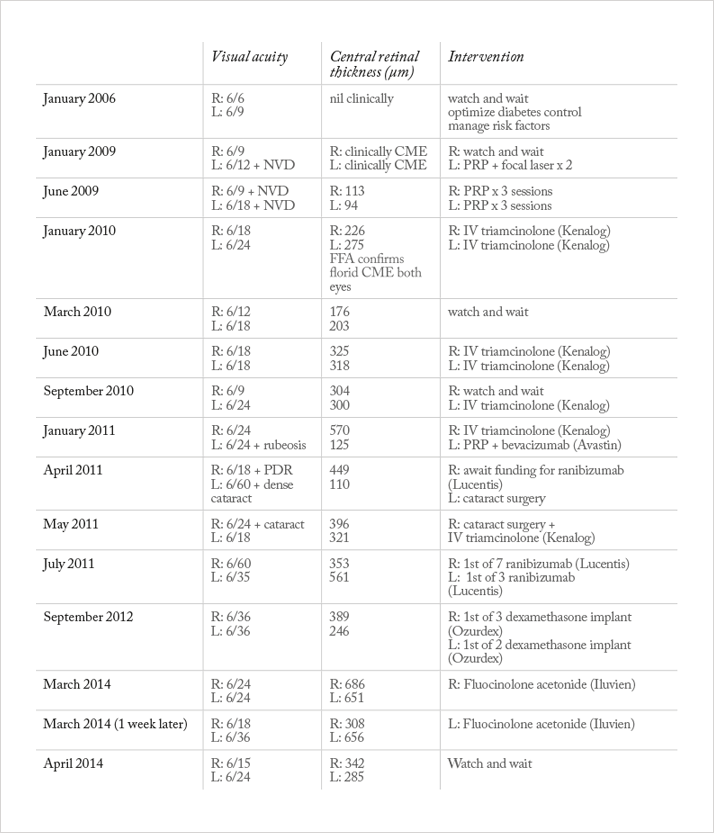

Management and outcome The patient was originally referred to the hospital by the UK Diabetic Retinal Screening Services for juxta-foveal macular edema. A few years later she developed optic disc neovascularization (NVD). Table 1 outlines all the treatments administered and their outcomes. The DME was initially treated with focal macular laser and the neovascularization with pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP). However, the DME persisted. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed central retinal thicknesses (CRTs) of 226 μm OD and 275 μm OS in January 2010. The free fluorescein angiography (FFA) at the time demonstrated non-ischemic florid DME. A decision was made to treat both eyes with intravitreal triamcinolone rather than further laser. The DME responded well to this and the visual acuity improved temporarily. When the DME worsened with stable visual acuity, we monitored the patient closely. However, when the visual acuity deteriorated, triamcinolone was administered twice more to each eye. This did not result in significant improvement in visual acuity or DME. When the patient developed rubeosis (January 2011), she was treated with intravitreal bevacizumab combined and PRP (at that time, ranibizumab had not been approved by UK National Institute of Clinical Health and Excellence (NICE)). The response was encouraging, with regression and edema. Upon recurrence of DME, we went on to use ranibizumab (following its approval by NICE) multiple times in both eyes. When the fovea-involving edema became non-responsive to ranibizumab we used intravitreal dexamethasone implant. The DME again subsided but the visual acuity remained poor at 6/24 or worse. The patient then developed bilateral cataracts, which we treated with phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation. Persistent DME and recent evidence (1) lead us to consider the fluocinolone acetonide implant, which we used in the right eye. We found a significant reduction in DME within a week (Figure 1). The visual acuity also improved, reaching 6/18 in the right eye. This was the best recorded acuity for over two years. Following these encouraging early results, we also treated the left eye with fluocinolone acetonide. We observed similar, favorable outcomes (Figure 2).

Discussion

In this case report we describe the outcomes of several different treatments we used to try and reverse declining visual acuity and increasing DME. We highlight the importance of using OCT in conjunction with FFA to identify suitability and location for focal laser. We used intravitreal steroids and anti-VEGF agents, rather than laser, for fovea-involving DME and found each of the pharmacological agents to have limitations in reducing the persistent DME in this case. We conclude, however, that unsatisfactory response to one class of intravitreal steroid does not preclude the use of another. Although our patient did not develop raised intraocular pressures, this is clearly always a concern and patients should be monitored closely.

The risks of administering multiple intravitreal injections, particularly that of endophthalmitis, should be carefully discussed with each patient. The risk of early cataract formation associated with steroid use, as was the case with our patient, is another important consideration (2). Management of diabetic neovascularization is challenging as the PRP-induced inflammatory response can worsen DME (3). The availability of different licensed steroid preparations provides both clinicians and patients with more choice and chance of satisfactory outcomes. In future management of our patient we may continue combining laser with pharmacological agents (3,4).

Conclusion

This case illustrates that for some patients, treatment of DME requires frequent, long-term monitoring and timely interventions. The decision to treat DME should be based upon visual acuity, OCT and FFA findings, the patient’s individual circumstances and threshold for risk.

With the advent of newer pharmacological agents, patients who had once run out of options are offered renewed hope. Despite the temptation, clinicians should not simply treat the OCT findings, rather, the patient should be assessed holistically in terms of their visual acuity and capacity to accept risks of intervention. We must not neglect ongoing patient education of risk factor control, which is likely to be of greater benefit in the long-term.

Statement: The patient consents to the submission of this case with her clinical photographs.

Read the next case report

References

- FAME Study Group, “Sustained delivery fluocinolone acetonide vitreous inserts provide benefit for at least 3 years in patients with diabetic macular edema”, Ophthalmol., 119(10), 2125–2132, (2012). The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, “Diabetic retinopathy guidelines”, (2012). H.R. McDonald, H. Schatz, “Macular edema following pan retinal photocoagulation”, Retina, 5, 5–10 (1985). T.A. Ciulla, A. Harris, N. McIntyre, et al., “Treatment of diabetic macular edema with sustained-release glucocorticoids: intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide, dexamethasone implant, and fluocinolone acetonide implant”, Expert Opin. Pharmarcother., Mar 24: Epub (2014).