Dry eye disease (DED) is burdensome for both doctor and patient for three main reasons: high prevalence, many causes, and – especially in the case of severe DED – little in the way of effective treatment options. Up to 100 million people globally are thought to be affected by DED to some extent, and for many reasons, it has been both underdiagnosed and undertreated. Milder forms are rarely vision-threatening, and a lot of people with DED will go to their pharmacist, buy an over-the-counter lubricant, self-treat and make do. It can therefore take years before these people navigate through the path of pharmacist, general practitioner, optometrist, general ophthalmologist, until finally getting to see a cornea specialist. Furthermore, some patients show the signs, but not the symptoms of DED, further delaying their presentation to an ophthalmology clinic. Nevertheless, a substantial volume of patients still present to ophthalmology clinics with DED. Indeed, it has been estimated that up to 60 percent of patients under the care of an ophthalmologist have some form of DED. Such patients are present in every subspecialty and in every clinic – even posterior segment specialists will talk of patients with fluctuating vision that leads to a DED diagnosis. Given that eye clinics are already busy enough dealing with aging baby-boomers with age-related ocular disorders, this is far from ideal. It’s also far from ideal if you’re a patient with DED. Symptoms include red, tired, irritated, itchy eyes, gritty or burning sensations, light sensitivity, fluctuating vision. Everyday tasks like driving a car, working with a PC, or even being in a room with a fan heater can all be painful undertakings.

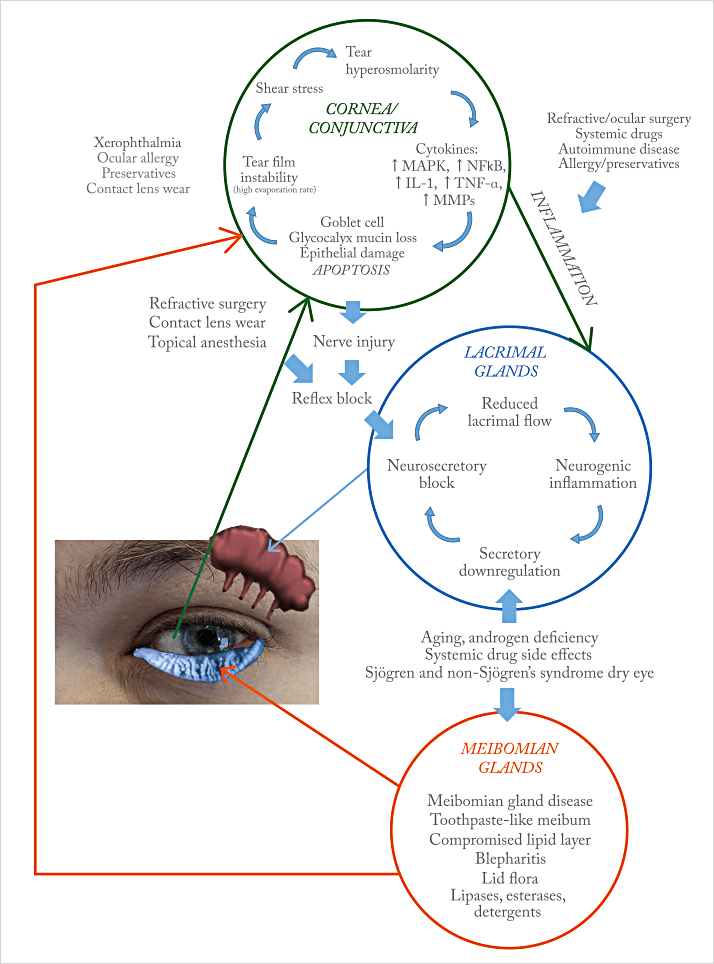

It’s not just the impact on quality of life that warrants concern; this is a disease that actively harms the eye, causing inflammatory damage to cells on the ocular surface. Then there’s the fact that it’s a disease with many causes: aging, air conditioning, air travel, autoimmune disease, androgen deficiency – these are just some that begin with the letter “A.” There really is no standard natural history of DED and there are many points where a patient can enter its vicious cycle (see Figure 1), and few places where patients can exit it – certain contributing factors (if present) like blepharitis or meibomianitis can be treated, which should help, but too often it isn't enough to exit the cycle. As DED can involve not just the cornea and conjunctiva, but also the lacrimal and meibomian glands too, there’s a complex interplay between the pathologies that develop in each site (Figure 1) that can all drive inflammatory pathways, accelerating ocular surface damage.

As we’ll explore in future issues of The Ophthalmologist, diagnosis is also a real challenge, but the big picture is that patients with DED are not happy. Gallup, the multinational management consulting company, conducted a poll in 2008 and found that:

- 72 percent of patients were recommended artificial tears for their dry eye problem by physicians,

- 82 percent of patients agreed that they wish there was something more effective to treat their dry eye, and

- 97 percent of patients reported that their dry eye condition is frustrating.